I want to talk (again) about competence. A large part of the crisis of confidence in American institutions is driven not just by the concern that our institutions are ideologically misguided, but by the all-too-accurate perception that they can’t do their jobs. We’ve seen this failure play out in both tragedy (the immense testing failures at the start of the pandemic) and farce (the Iowa Democrats’s inability to count their caucus).

And it just keeps happening. See, for example, the Scott Gottlieb Wall Street Journal piece we highlighted in our Morning Dispatch. It begins:

The Covid epidemic in the South has strained the country’s capacity to keep up with the demand for testing. Six months into the pandemic, we still don’t have enough supplies, equipment or lab services. There’s no national plan for effectively allocating the capacity that does exist or providing a sufficient surge where it’s needed suddenly.

The system is overwhelmed. Major commercial labs are reporting turnaround times of around seven days, and patients say it’s often longer. Without a confirmed diagnosis, many infected patients don’t isolate themselves or get treatments.

This is all unfolding even though responding to the pandemic has been job one for state and federal governments for months.

No one thinks responding to a pandemic is easy, but for the health of our republic, an effective response is necessary. Here’s another basic function of government that’s not easy at all. It’s simply this—quelling violent civil unrest while preserving constitutional rights.

Moreover, those two obligations—restoring peace and protecting the Constitution—are inextricably linked. Violate the Constitution in the attempt to restore the peace, and you inflame the resistance. Fail to keep the peace, and you put immense pressure on law enforcement, pressure that law enforcement often doesn’t handle well. Absent effective leadership and professionalism, a city can fall into a vicious cycle of violence, police misconduct, more violence, and more misconduct.

In fact, there is evidence that’s exactly what’s occurred in Portland. I would urge everyone to read this extraordinary piece of on-the-ground reporting from Robert Evans from the website Bellingcat. It represents the only comprehensive, start-to-present account I’ve read from any individual who has been there from day one.

It describes a series of encounters that are quite different from the caricatures you see in conservative press (of the Portland government “letting the violence happen”) and the idealized versions you often read in more progressive outlets. There has, in fact, been sustained violence and disorder from the protesters. There have also been numerous inexcusable acts of violence from police, some caught on video.

The picture that’s emerging is of weeks comprehensive incompetence in the face of a challenging test. Even worse, just as the crisis arguably slightly eased (perhaps as much due to exhaustion as to effective policing) and numbers of protesters dwindled, the Trump administration stepped in with its own incompetence and threw gasoline on a fading fire.

Much of the controversy over the Trump administration’s deployment of camouflaged federal police to Portland has focused on the deployment’s legality, less on its effectiveness. As a legal matter, the Trump administration is on solid legal ground to conduct a limited law enforcement mission in Portland.

Federal law enforcement has the authority to protect federal buildings, it has the authority to enforce federal laws, and (under federal law) federal officers do not have to disclose their identity or the identity of their agency. Indeed, there are times when removing names from officers’ uniforms is necessary for their own protection.

(For those readers who seek a comprehensive legal explainer, I highly recommend this Lawfare piece by University of Texas law professor Steve Vladeck.)

Why do I say the Trump response is incompetent? It commits the cardinal sin of responding to civil unrest, in that it introduced enough additional force to inflame the resistance but not enough additional force (or effective tactics) to quell the resistance. As the military has long understood in the counterinsurgency context, there is a difference between “presence”—which can enrage the population—and “effective” or “decisive” presence, which can take command of the situation.

Now, let’s compound the problem with three additional factors. First, the additional deployment is occurring over the objection of state and local authorities. Second (absent invocation of the Insurrection Act and deployment of actual troops), federal officers lack the legal authority to impose general order in the city. And third, there is already evidence of individual constitutional violations—including beating a Navy veteran and seriously injuring a protester by shooting him in the head with a non-lethal munition.

No, wait. Let me add a fourth complication. The president’s June 26, 2020, Executive Order on Protecting American Monuments, Memorials, and Statues and Combating Recent Criminal Violence is written so broadly that it raises the reasonable concern that other cities may well face a stepped-up military-style federal police presence—whether mayors and governors object or not.

Thus, we’re left with a state of chaos and confusion. Are federal officers in Portland to restore order? Or merely to protect federal buildings? Or is the mission a tangled hybrid of both? Acting Homeland Security Secretary Chad Wolf’s statement condemning violence in Portland was a mess:

“The city of Portland has been under siege for 47 straight days by a violent mob while local political leaders refuse to restore order to protect their city. Each night, lawless anarchists destroy and desecrate property, including the federal courthouse, and attack the brave law enforcement officers protecting it.

A federal courthouse is a symbol of justice – to attack it is to attack America. Instead of addressing violent criminals in their communities, local and state leaders are instead focusing on placing blame on law enforcement and requesting fewer officers in their community. This failed response has only emboldened the violent mob as it escalates violence day after day.

This siege can end if state and local officials decide to take appropriate action instead of refusing to enforce the law. DHS will not abdicate its solemn duty to protect federal facilities and those within them. Again, I reiterate the Department’s offer to assist local and state leaders to bring an end to the violence perpetuated by anarchists,” said Acting Secretary Chad Wolf

Read the statement again. It’s completely unclear whether the DHS is in the city to protect federal property and prosecute federal crimes (something that’s squarely in its mission) or to “bring an end to the violence” (something it lacks the legal authority to do). When clarity is necessary, confusion reigns.

Again, I do not want to imply that the task before the Department of Homeland Security is easy. It is not. But there are better ways to step into one of the most tense pressure cookers in the United States than through rolling up in military-style uniforms, arresting people on the street, and putting them in unmarked vans:

Does the administration not understand that right-wing militias often dress themselves in military-style uniforms and arm themselves with military-style weapons? Don’t such actions create the potential for profound confusion and truly volatile confrontations? Can you imagine an action better-calculated to exacerbate existing mistrust and political paranoia?

It is way too much to call the federal deployment to Portland an “occupation.” And this statement, from Nancy Pelosi, is extraordinarily over the top:

Critics of the Trump administration need to reckon with the fact that there does exist an obligation to protect federal buildings and enforce federal law. At the same time, the results of federal action are speaking loudly and clearly. There is no de-escalation. Instead, there is greater division, and there is greater unrest. Our national fabric tears just a little bit more.

Calling for “law and order” (or even tweeting it in all caps) does not impose law and order. Applauding an administration for “fighting” is inadequate if the “fight” is counterproductive.

American military history, for example, is littered with figures who “fought,” yet they fought poorly. There is a reason why names such as McClellan, Burnside, and Hooker are not remembered fondly by students of the Civil War. They were given an extraordinarily difficult task—defeat the Army of Northern Virginia—and they failed. We remember and honor Ulysses S. Grant because he did not. When it’s all said and done, the difficulty of the necessary task is not an excuse for failure at the necessary task.

Regardless of ideology, there is an irreducible basic obligation of good governance that many of our leaders are, quite simply, failing. There is no way that one can look at more than 50 days of sustained violence (including unlawful police violence) in the heart of a major American city and declare a job well done. There is no way—in the absence of an unforeseen dramatic change—that we can look at the escalation surrounding the Trump administration’s deployment of federal police and declare a job well done.

And what is that job? Let’s go back to the beginning. Quell the unrest and uphold the Constitution. Both elements are necessary. Neither has been accomplished. Peace, it seems, is not at hand.

One last thing …

The news cycles have been grim. So it’s time for the relative lightness of my latest YouTube obsession … mass extinction events. Sarah and I want to dedicate a future edition of our podcast to a guest expert on the Yellowstone supervolcano. Until that day, enjoy a taste of the calamity to come:

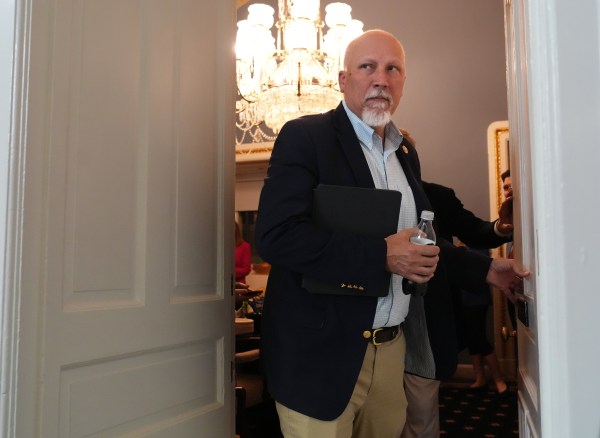

Photograph by Nathan Howard/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.