I want to start with a story about cancel culture—the cancel culture that existed on a cold December night in 1860 in Boston, Massachusetts. In our popular imagination, Boston in 1860 was a good place, the heart of abolitionism and unionism. But not that night. That night a mob silenced a great man.

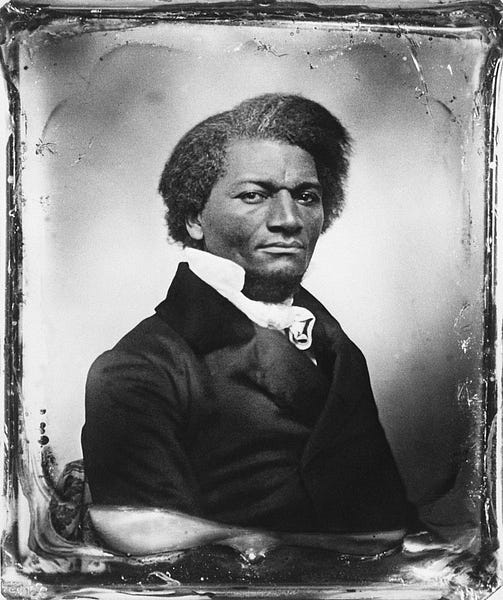

Frederick Douglass was supposed to address a meeting called, “How Can American Slavery Be Abolished?” It was a tense time in the United States, at the beginning of the most extreme and violent national test in our history. Abraham Lincoln had just been elected. In less than three weeks South Carolina would secede. The rest of the South would fall like dominoes, and then would come our most brutal war.

Douglass could not speak. A mob stormed the stage, with police looking on. Abolitionists tried to restore order, but violence reigned. Eventually, the police moved–not to clear the mob to protect speech, but rather to clear the meeting hall and end the event.

In one condensed moment, we saw the kind of mob action and police passivity that we sometimes still see today. Private citizens mobilized to block speech, and rather than protect liberty, the police saw fit to restore “order” instead. But American order requires the protection of liberty.

Douglass refused to be silenced. Days later, he mounted the stage at Boston’s Music Hall, delivered his prepared remarks, and then added an additional statement that goes down in history as one of the most compelling defenses of free speech ever made.

Called simply “A Plea for Freedom of Speech in Boston,” it begins with a tribute to the city, but even in Boston, Douglass says, “the moral atmosphere is dark and heavy.” The “principles of human liberty,” he warns, “find but limited support in this hour a trial.”

Every single student in America should read this speech–not just because Douglass rightly decries his lost liberty, but because he explains why the right to free speech is so precious.

No right was deemed by the fathers of the Government more sacred than the right of speech. It was in their eyes, as in the eyes of all thoughtful men, the great moral renovator of society and government. Daniel Webster called it a homebred right, a fireside privilege. Liberty is meaningless where the right to utter one’s thoughts and opinions has ceased to exist. That, of all rights, is the dread of tyrants. It is the right which they first of all strike down. They know its power. Thrones, dominions, principalities, and powers, founded in injustice and wrong, are sure to tremble, if men are allowed to reason of righteousness, temperance, and of a judgment to come in their presence.

“Slavery cannot tolerate free speech,” he declared. And in words that should be burned into our civic hearts, he noted that there exists not just a right to speak but a right to hear. “To suppress free speech is a double wrong. It violates the rights of the hearer as well as those of the speaker.” Free speech applies to us all, and that right is rooted in our humanity, the inherent dignity of man:

The principle must rest upon its own proper basis. And until the right is accorded to the humblest as freely as to the most exalted citizen, the government of Boston is but an empty name, and its freedom a mockery. A man’s right to speak does not depend upon where he was born or upon his color. The simple quality of manhood is the solid basis of the right—and there let it rest forever.

I begin with Frederick Douglass for a reason– last week a middle school teacher I know reported that a group of parents were upset about an assignment that asked students to read, you guessed it, Frederick Douglass. Apparently, there are more than a few parents who believe it is a grievous injury to hear from America’s critics, even when one of its critics was one of its greatest men.

I have never in my adult life seen anything like the censorship fever that is breaking out across America. In both law and culture, we are witnessing an astonishing display of contempt for the First Amendment, for basic principles of pluralism, and for simple tolerance of opposing points of view.

At this point the cancel culture stories are so common it’s hard to know where to start. In the last several days we’ve seen concerted efforts to fire The View host Whoopi Goldberg for ignorant comments about the Holocaust and Georgetown law school lecturer Ilya Shapiro for a poorly worded tweet arguing for a race-blind Supreme Court nomination. Both Goldberg and Shapiro apologized, but they’ve both been suspended.

Yet the worst examples of cancel culture don’t apply to famous or prominent people at all. The most haunting piece I’ve read about rising American intolerance was penned by my friend Yascha Mounk in The Atlantic. Called “Stop Firing the Innocent,” it details the ordeals of ordinary people who become involuntarily notorious. At this point cancel culture is so plainly, obviously real, that I’ll just re-quote progressive writer Kevin Drum:

And for God’s sake, please don’t insult my intelligence by pretending that wokeness and cancel culture are all just figments of the conservative imagination. Sure, they overreact to this stuff, but it really exists, it really is a liberal invention, and it really does make even moderate conservatives feel like their entire lives are being held up to a spotlight and found wanting.

At the same time that the evidence of far-left intolerance is overwhelming, a few of us have been on a very lonely corner of conservatism, jumping up and down and yelling about the new right, “Censorship is coming! Censorship is coming!”

And we were correct.

First, it’s long been clear that the new right was replicating many of the tactics of the far-left, often proudly and intentionally. How many times have I heard “Fight fire with fire. Make the other side play by its own rules”? Since 2015, right-wing cancel culture has been mainly aimed at conservative Trump critics, but now it’s metastasizing.

The anti-woke movement is building to a fever pitch. Attempts to ban books abound, and dozens of pieces of legislation have been introduced (and many passed) that don’t just seek to narrowly regulate and define public K-12 curriculum, but also to sharply restrict the sharing and teaching of ideas.

These bills are broadening in scope and in number. The invaluable Acadia University professor Jeffrey Sachs has been doing yeoman’s work cataloging these bills, and he published an impressive roundup last month. At least 122 bills have been filed in 33 different states, and 12 have become law in 10 states (so far).

Ominously, 38 of these bills now target higher education. I say “ominously” because teaching and scholarship in public higher education enjoys a level of constitutional protection that public K-12 schools do not. As the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education’s Joe Cohn explains, “while legislators have broader (but not unlimited) authority to set K-12 curriculum, the First Amendment and the principles of academic freedom prevent the government from banning ideas from collegiate classrooms.”

The Supreme Court could not be more clear about the special importance of the First Amendment in the university setting. Cohn quotes these famous words from Sweezy v. New Hampshire:

The essentiality of freedom in the community of American universities is almost self-evident. No one should underestimate the vital role in a democracy that is played by those who guide and train our youth. To impose any strait jacket upon the intellectual leaders in our colleges and universities would imperil the future of our Nation. No field of education is so thoroughly comprehended by man that new discoveries cannot yet be made. Particularly is that true in the social sciences, where few, if any, principles are accepted as absolutes. Scholarship cannot flourish in an atmosphere of suspicion and distrust. Teachers and students must always remain free to inquire, to study and to evaluate, to gain new maturity and understanding; otherwise, our civilization will stagnate and die. (Emphasis added.)

I quoted this exact passage for years as I filed (successful) lawsuit after lawsuit to strike down university speech codes. When colleges passed speech codes to suppress discourse on campus, they betrayed their very purpose. The call was coming from inside the house.

Speech codes are on the wane, thankfully. Litigation does work. According to FIRE’s research, the prevalence of clearly unconstitutional speech codes on leading campuses dropped from more than 70 percent of campuses in 2009 to 21.3 percent in 2021.

But now the speech code movement is coming from the outside. Again, here’s FIRE’s Cohn:

In legislatures across the country, including in states like Alabama (HB 8, HB 9, HB 11, and SB 7), Florida (HB 57 and SB 242), Indiana (HB 1134 and SB 167), Iowa (HF 222), Kentucky (HB 18), Missouri (HB 1484, HB 1634, and HB 1654), New Hampshire (HB 1313), New York (A 8253), Oklahoma (HB 2988), and South Carolina (H 4799), the bills contain unconstitutional bans on what can be taught in college classrooms. They must not be enacted in their current form.

Yet even when a state agency can regulate the expression of ideas, should it? After all, most cancel culture incidents don’t implicate the First Amendment either. Employers can fire you for your speech. Social media can block any of us from access to their platforms. But in law as in culture, the question of “can” is separate from the question of “should.”

For example, a school board can remove the book Maus from its eighth-grade curriculum (because of profanity and mouse nudity), but should it? A school board can remove To Kill a Mockingbird (for alleged racial insensitivity) from a required reading list, but should it?

And if you think state bills are only banning toxic wokeness and protecting kids from left-wing racism and identity politics, think again. Even some of my essays can’t be assigned in North Dakota:

Why does Professor Sachs make this assertion? On November 12, the governor signed a bill that makes it unlawful to include “instruction relating to critical race theory in any portion of the district’s required curriculum . . . or any other curriculum offered by the district or school.”

And what is critical race theory? According to the statute, it’s the “theory that racism is not merely the product of learned individual bias or prejudice, but that racism is systemically embedded in American society and the American legal system to facilitate racial inequality.”

That’s not the definition of critical race theory, which is a far more complex and nuanced concept than the sentence above. It’s but one version of a definition of systemic racism. Moreover, even North Dakota’s false definition of CRT is still broad and vague to the point of uselessness. It easily encompasses my assertions in the essay Professor Sachs highlighted, and it renders multiple editions of the French Press either outright unlawful as assignments in North Dakota or so legally problematic that assigning them presents an unacceptable personal risk.

In Board of Education v. Pico, a 1982 Supreme Court case that cast doubt on the ability of public schools to ban library books on the basis of their ideas alone, the court’s plurality described a purpose of public education as preparing “individuals for participation as citizens,” and as vehicles for “inculcating fundamental values necessary to the maintenance of a democratic political system.”

Systematically suppressing ideas in public education does not help our students learn liberty, nor does it prepare them for pluralism. It teaches them to seek protection from ideas and that the method for engaging with difference is through domination.

Our nation is a diverse pluralistic constitutional republic, and as James Madison noted in Federalist No. 10, we cannot respond to the inevitable rise of competing factions by suppressing liberty, tempting as that always is. Madison was shrewd and realistic enough to recognize that liberty empowers factions. As he put it, “Liberty is to faction what air is to fire, an aliment without which it instantly expires.”

At the same time, however, “it could not be less folly to abolish liberty, which is essential to political life, because it nourishes faction, than it would be to wish the annihilation of air, which is essential to animal life, because it imparts to fire its destructive agency.”

In a previous newsletter, I mounted a Christian defense of American classical liberalism, and I made the case that–while no system of government is perfect–American classical liberalism does possess two cardinal virtues. Its protections of liberty recognize both the dignity and the imperfection of man.

And few liberties encompass both that dignity and imperfection more than the right to speak. The violation of that right–the deprivation of that dignity–can inflict a profound moral injury on a citizen and it can help perpetuate profound injustices in society and government. As Douglass noted, free speech is the “dread of tyrants.”

Moreover, as John Stuart Mill’s argument for free speech demonstrates, free speech rests on a foundation of humility. FIRE’s Greg Lukianoff has written eloquently about “Mill’s trident,” the three-part argument for free inquiry. Summarizing Mill, Greg articulates “three possibilities in any given argument:

-

You are wrong, in which case freedom of speech is essential to allow people to correct you.

-

You are partially correct, in which case you need free speech and contrary viewpoints to help you get a more precise understanding of what the truth really is.

-

You are 100% correct, in which unlikely event you still need people to argue with you, to try to contradict you, and to try to prove you wrong. Why? Because if you never have to defend your points of view, there is a very good chance you don’t really understand them, and that you hold them the same way you would hold a prejudice or superstition. It’s only through arguing with contrary viewpoints that you come to understand why what you believe is true.

In short, I value free speech, not so much because I’m right and you need to hear from me, but rather because I’m very often wrong and need to hear from you. Free speech rests upon a foundation of human fallibility.

As American animosity rises, we simply cannot censor our way to social peace or unity. We can, however, violate the social compact, disrupt the founding logic of our republic, and deprive American students and American citizens of the exchange of ideas and of the liberty that has indeed caused, as Douglass prophesied, “thrones, dominions, principalities, and powers, founded in injustice and wrong” to tremble in the face of righteous challenge.

One more thing …

In this week’s Good Faith podcast Curtis and I dive deep into the balance between grace, mercy, and accountability in public life. When should we forgive and move on? When do we forgive and impose accountability? How does one provide justice and grace?

Those are hard questions, and they of course don’t have easy answers. Please let us know your thoughts, either in the comments below or in the comments to the podcast itself. And, as always, thank you for listening!

One last thing …

I’m going to depart from tradition and post a different kind of video. It’s not a song (though it does feature a musician). Dua Lipa asked Stephen Colbert about how his faith influenced his comedy. His answer was brilliant and moving. Watch:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.