The spring of 1998 was the best of times for our family, and it was almost the worst of times. I’ll never forget the way Nancy told me that she was pregnant. I came home from work, and she was waiting for me at the door with a present. I unwrapped it, and I was completely puzzled for about three seconds. It was a tiny baby onesie. Then, suddenly, the stupidity wore off, and we yelled and hugged and celebrated the wonderful news.

Then, weeks later, Nancy started to bleed. It was late enough in the pregnancy that it came as a shock, and Nancy raced to the doctor. He put her on bed rest, but he was grim. We’ll never forget his words. “You might need to call off the celebrations,” he said. We felt sick.

So Nancy went on bed rest. She barely moved for days. The bleeding stopped, and we went back to the doctor to determine whether our baby was still alive. When I close my eyes, I can still hear that wondrous noise—the unmistakable high-pitched sound of our daughter Camille’s heart beating fast and strong. Words can’t describe our relief and delight.

Even though I was a pro-life lawyer and activist, politics was the furthest thing from my mind. I couldn’t think. I could only feel joy.

But I’ve thought about that moment for years—and I thought about it even more last year as Camille endured a pregnancy scare (and NICU stay) that made our few-day ordeal with her seem light and easy by comparison. As I’ve reflected on God’s great gift of life, I’ve had two thoughts that have helped clarify exactly how I think about the law of abortion and the culture of life.

First, while Nancy and I were overjoyed to hear Camille’s heart, our joy and our desperate desire for Camille’s health and well-being did not make her alive or grant her life meaning. Her little heartbeat signified the existence of a human being in a temporarily dependent state who possessed immense independent worth. From a legal perspective, a just nation recognizes that worth and protects that life.

Second, I also knew that the only way to truly and comprehensively protect life was to build and foster a culture in which mothers and fathers greet new life with joy, not fear. With delight, not despair. A just nation would have to also be a transformed nation, one where the desire for abortion had dramatically diminished. Not only is there no other way, it is the best way—the way that most ensures that children grow up in homes full of love.

I’m writing this newsletter as our political class is busy tearing itself apart over abortion. The Supreme Court refused to stay enforcement of a Texas state law that prohibits abortion after a heartbeat is detected. As I explained in a newsletter this week, the law is highly unusual. I have profound reservations about it.

The law bans abortion after a heartbeat is detected (a position I support), but it does so in a way that is engineered both to evade pre-enforcement judicial review (dangerous) and to empower any citizen (except state officials) to file suits against anyone who performs or “aids or abets” the performance of an abortion (even more dangerous).

That means that if a person believes his ex-girlfriend, friend, or acquaintance obtained an abortion, they can sue the doctor, the nurse, the receptionist, the mom who paid for it, and the boyfriend who drove her to the clinic.

Yes, those people can mount legal defenses regarding the constitutionality of the statute or their actual participation in the abortion—perhaps the plaintiff sued the wrong nurse, or the mom didn’t know the money she loaned her daughter was for an abortion, or the boyfriend didn’t realize where he was taking his girlfriend until after they arrived—but if they prevail and defeat the lawsuit, they’re still out legal fees that could financially break the defendants.

What if the woman didn’t get an abortion at all? What if she miscarried, and the plaintiff files suit thinking she obtained an abortion? How many thousands of dollars in legal fees would the defendants (including, possibly, grieving family members) have to pay to defend themselves against a random citizen before that citizen has to drop the suit? “I’m sorry” wouldn’t begin to cover the dreadful costs involved.

Thus, even if Roe and Casey fall, and Texas is legally able to ban abortions after a heartbeat is detected, this law is still unjust. To help you understand, let’s remove the hypothetical from the abortion context. If a drunk driver kills my neighbor, I don’t have a right to collect money from the man who killed him or her. Their tragedy is my economic opportunity? No.

To be pro-life does not mean supporting every possible strategy, even if only temporarily successful (a Texas state court has already issued a broad injunction against the law), designed to ban or limit abortion. Strategies designed to ban abortion do not necessarily help end abortion, and ending abortion is the ultimate aim of the pro-life movement.

I don’t think most Americans appreciate how much the debate over abortion has changed in the last thirty years of American life. Two changes are particularly important. One is profoundly negative, and the other is extraordinarily positive.

First, the legal and political debate over abortion has become purely partisan at exactly the time when our nation’s profound polarization means that party affiliation is becoming central to millions of Americans’ personal identities.

Thirty years ago there was a robust pro-life wing of the Democratic Party. Even 15 years ago, when I moved back to Tennessee, my congressman was a proudly pro-life Democrat. My heavily Republican district voted him out in 2010. It preferred a “pro-life” candidate who faced evidence that he tried to pressure a girlfriend to abort their child and supported his ex-wife’s two abortions.

And now? Elected pro-life Democrats are very, very hard to find. Even worse, as the parties move away from each other on a host of important political issues—and as the GOP continues to embrace Donald Trump and his ethos and contains an ever-expanding coalition of cranks and radicals—it is increasingly difficult to ask Democrats to lend any aid and comfort to a party that they find unmoored from even basic decency, integrity, and truth itself.

Or, as I’ve heard so many believers from many faiths say: “I’m pro-life, and I want the law to protect the unborn. I welcome refugees. I want to address the contemporary reality and persistent legacy of racism. I want politicians to be people of good character and fundamental integrity. Where do I go? Where is my home?”

To my friends and colleagues in pro-life America, if you want to make the political and legal pro-life movement persuasive to Americans, it is imperative that you at least make the political tribe you ask them to join both decent and humane. And a pro-life position on abortion does not by itself render any political party competent or moral or worth your vote.

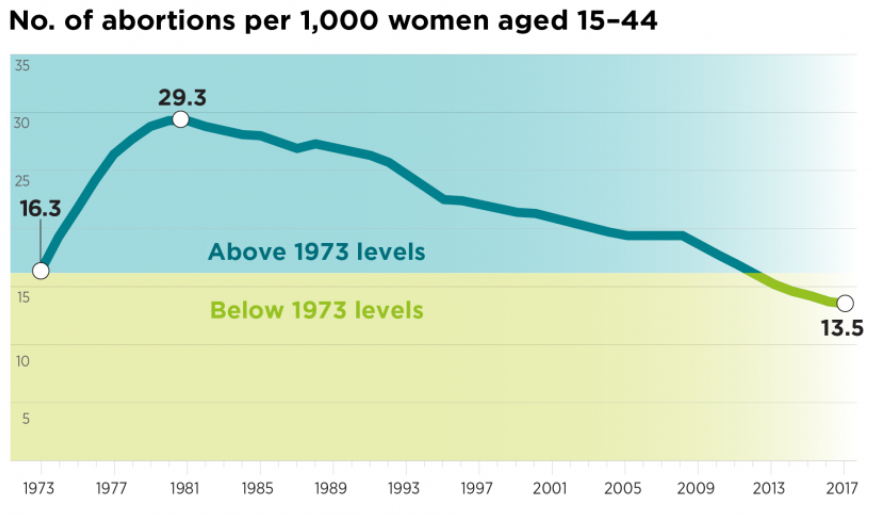

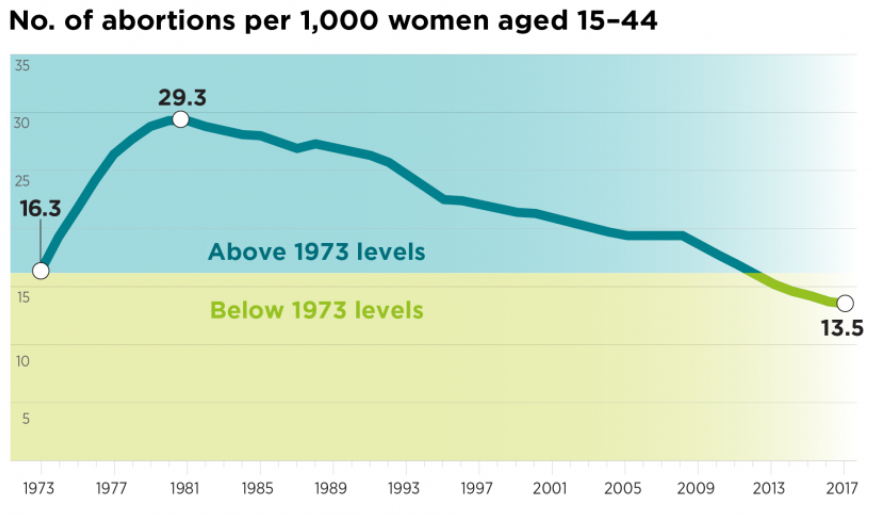

But let’s move from the bad news to the good news. And “good” really is an understatement. It’s great news. As I’ve mentioned in previous pieces, this great news is captured by the chart below:

The abortion rate is now lower than it was when Roe was decided (and yes, the data takes chemical abortions into account). That means it’s now lower than it was when abortion was illegal or sharply limited in most states in the union. The abortion rate decreased during pro-life presidencies and pro-choice presidencies. And when you look at the state-by-state data, the increase or decrease in recent years doesn’t fit neatly on a red/blue spectrum:

What is going on? So many things. Let’s list a few of the potentially relevant factors—increased availability of contraception, the so-called “sex recession” under which young people are having less sex, a general decline in unintended pregnancies. And that’s just the start.

But there’s something else—something very important. I’ve cited this 2020 Notre Dame study before, but I truly can’t cite it enough. The research team, led by Dr. Tricia Bruce (credit to whom credit is due!) conducted hundreds of in-depth interviews of demographically representative subset of Americans who were not recruited specifically to discuss abortion. It’s the best single snapshot of what Americans actually believe about this most fraught of topics.

In one sense, their findings were unsurprising. The polling of their general attitudes tended to match public polls. A minority of respondents supported flat abortion bans. A minority supported its legality “in all circumstances.” A majority were somewhere in the middle. But when you drilled down farther, you found this fascinating conclusion:

None of the Americans we interviewed talked about abortion as a desirable good. Views range in terms of abortion’s preferred availability, justification, or need, but Americans do not uphold abortion as a happy event, or something they want more of. From restrictive to ambivalent to permissive, we instead heard about the desire to prevent, reduce, and eliminate potentially difficult or unexpected circumstances that predicate abortion decisions … Stories from those who have had abortions are likewise harrowing, even when the person telling it retains a commitment to abortion’s availability.

In concrete terms, this means that regardless of a person’s political and legal preferences, the argument for life applied person-to-person, face-to-face will so very often fall on fertile ground.

That’s why, ultimately, the pro-life movement has to transcend politics.

I apologize for being a broken record, but it often takes repetition to implant ideas into the cultural bloodstream. And here’s my repetition. I can think of few contentious public issues more amenable to the triple, interlocking responsibilities of Micah 6:8 than the issue of abortion. Recall the verse: “He has shown you, O mortal, what is good. And what does the Lord require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God.”

Act justly. The beating heart of an unborn child isn’t valuable because its parents love it and want to bring it into this world. It has independent value. It is the heart of a small person, “fearfully and wonderfully made” and created in the image of God. A just nation protects that life. Indeed, as our nation’s founding document declares, protection of “life” is one of the “unalienable rights” for which “governments are instituted among men” to secure.

But just ends require just means, and any path to justice that forgets that principle creates its own victims and imposes its own pain.

Love mercy (some translations say “love kindness”). This is the imperative that doesn’t just require us to embrace mothers and children individually, it should also cause us to think hard about how mercy and kindness can be systemic values. A nation should prioritize the protection of the weak and vulnerable in its midst. It should make family formation easier, not harder.

We shouldn’t think government can do too much, but neither can we pre-emptively declare that it can do too little. That’s why I support experimenting with child allowances—putting cash directly into the hands of new and (under Mitt Romney’s proposed plan) expectant parents. If economic insecurity is a reason why women choose abortion (and it is), then easing that insecurity can be concretely pro-life.

But “system” isn’t a synonym for “government.” It’s a crying shame that crisis pregnancy centers often operate on shoestring budgets. It’s deeply sad that most pro-life Americans’ entire concrete commitment to the cause is summed up in a vote every two to four years, or perhaps in occasional arguments on Twitter or Facebook. “Pro-life” shouldn’t be a political position, it should be a way of living—consistently, faithfully, and sacrificially.

Walk humbly. This is perhaps the most challenging command of all. When a person feels moral clarity and a burning sense of purpose, they can often underestimate the complexity of an issue and overestimate their own wisdom in solving the problem. Virtuous purpose can become self-righteousness at the speed of our own sin.

My own approach is to pray for wisdom and work with anyone who will work with me on any positive front. When it comes to the cause of life, the distressing tendency is to view each person as an object of all-or-nothing friendship and respect. But a person who agrees with me 50 percent or even 20 percent of the time is not my 100 percent enemy. Dive into that 50 percent or 20 percent and work from there. The pro-life message should be clear—I’ll be open to you. Whether you’re closed to me is up to you.

For most of us, politics is abstract. Even for political obsessives, it’s not a profession. It’s more like a hobby. But when a woman becomes pregnant, there is nothing more real, nothing more immediate. That’s when a heart flares full of love, yes, but sometimes full of fear and even dread. And that’s where a loving pro-life movement or loving pro-life family and friends can meet a person where they are and do all they can to turn fear into joy and dread into delight.

And another thing …

Many of you ask about our granddaughter Lila. One year ago this week, Camille received the terrible diagnosis that Lila suffered from profound and life-threatening birth defects. An extended stay in the NICU was her best-case outcome. And, well, look at her now. Thank you for your many thousands of prayers. I’m so grateful.

One more thing …

If you’re reading and want to dive deeper into the weeds of both the law and politics of one of the most contentious and confusing abortion controversies in years, I’d invite you to listen to two podcasts.

In the first, my brilliant Advisory Opinions co-host and I dive deep into the Supreme Court’s decision to let the Texas law go into effect. Simply put, the case doesn’t mean what you think it means. Listen here.

In the second, Sarah and I discuss the politics and cultural impact of the Texas law at length, and we spend an extended amount of time discussing the difference between a movement aimed at banning abortion versus a movement aimed at ending abortion. Listen here.

One last thing …

Speaking of humility, it’s been months and months since I ended with this song, but it speaks so clearly to the profound difficulty of engaging our world on complex topics, and necessity of faith and love as bedrock principles, come what may:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.