It happens every single time Israel and Hamas go to war. We see the same arguments the instant Hamas’s rockets go up and the IDF’s bombs fall down. Immediately a great many of Israel’s critics latch on to two profoundly wrong narratives and then spread those wrong narratives far and wide, undermining the formal truths of an intractable conflict.

Those two wrongs are simple: 1) that Hamas is lashing out at Israel because it possesses “legitimate grievances” against Israel; and 2) that Israel’s response—in large part because it’s almost always deadlier than Hamas’s attack—is “disproportionate” to the threat and thus both illegal and immoral. Let’s deal with each in turn.

First, I want to be abundantly clear that I am not asserting that Palestinians do not possess legitimate grievances against Israel. Israel is not perfect, and its American allies and supporters should not pretend that it is. It is worth untangling and understanding, for example, the land dispute that’s triggered violence in East Jerusalem. It’s worth questioning Israeli settler policies and practices, and it’s worth asking whether the West Bank is now so carved up by Israeli settlements that it will be increasingly difficult to form a viable Palestinian nation as part of any permanent “two-state” solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

But I want to be equally clear that none of that analysis applies to the actions of Hamas, a jihadist terror organization whose stated aim is abundantly, perfectly clear: the destruction of the state of Israel. Its dedication to jihad is obvious from its charter. Its slogan is, “Allah is its target, the Prophet is its model, the Koran its constitution: Jihad is its path and death for the sake of Allah is the loftiest of its wishes.”

Hamas views the establishment of modern Israel as an “usurpation” of Muslim land, and “the day that enemies usurp part of Moslem land, Jihad becomes the individual duty of every Moslem.” Thus, there is an obligation to wage holy war against Israel: “In face of the Jews’ usurpation of Palestine, it is compulsory that the banner of Jihad be raised.”

The Charter is a chilling document. It’s far from a simple declaration of war. Instead, it outlines how the entirety of Palestinian society should be organized and mobilized for jihad. Israel’s fundamental sin is its existence. That’s the “grievance” against Israel, and it is not legitimate. Any other case or controversy that triggers Palestinian anger is but a pretext for Hamas to re-initiate open hostilities in a war that it’s waged since its founding.

Let’s put this in the simplest terms. Imagine that your family is locked in a long, bitter land dispute with a neighboring family. It’s complicated, and while the neighbors have lashed out violently and unfairly, you’re not always proud of your family’s actions either. In fact, if you sat down to speak to each other, the two families could air their mutual grievances for days. In optimistic moments, however, you think it’s still possible to work out the dispute.

But not with everyone. Across the property line, some of the neighbors want to kill you and take your land. That’s their whole goal. Their version of the “land dispute” is they dispute your right to the land at all. And sometimes, out of nowhere, they’ll come charging at you with knives in their hands, intent on killing and maiming the people you love.

So you build walls. You hire security. You’ve got more money than they do. You’ve got better weapons than they do. But they’re always there, hoping to get a chance to kill, and they’re going to keep trying to kill you and members of your family until you leave, you die, or you kill them. That’s what it’s like to live next to Hamas.

And that brings us to the next wrong narrative of Israel’s war with Hamas—that in defending itself against its murderous neighbor, Israel constantly reacts “disproportionately” to the threat and thus responds to Hamas’s illegal attacks with illegal attacks of its own. This is a constant refrain from Israel’s critics, including from critical American politicians.

It’s a critique with a certain surface appeal, in part because the word “proportional” has a colloquial definition of “corresponding in size or amount to something else.” So when Palestine fires volleys of rockets that Israel (mostly) intercepts while Israel drops bombs that can and do sometimes kill scores of Palestinians, it can look like Israel’s response is “disproportionate” because its outcome is not equivalent.

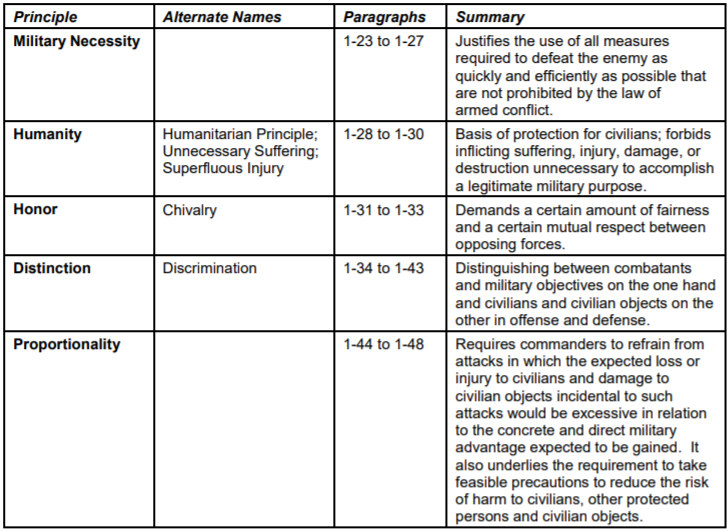

But that’s not how the law of war works. I’ve written about the Law of Armed Conflict (LOAC) many times before, but it’s worth a brief refresher. This chart from the U.S. Army’s Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Land Warfare is useful in outlining the key concepts:

The three most relevant are necessity, distinction, and proportionality—and note that proportionality does not require equivalence. It instead requires commanders to “refrain from attacks” that would cause injury to civilians and civilian objects that “would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage to be gained.” In layman’s terms, this does not mean using the same kinds of attacks as the enemy, but rather making attacks that are designed as much as possible to damage the enemy without harming anybody else.

Think of it like this. If you’re taking rifle fire from a house, proportionality does not require you to respond to rifle fire with rifle fire. It would, however, require you to use weapons that would end the threat without excessive collateral damage. In practice, that often means dropping a bomb on the house, or firing a missile at the house. It’s the safest way of neutralizing the threat without exposing your own troops to excessive danger. So, yes, you can bring a JDAM to a gunfight. That’s what Israel often does. That’s what we often do.

As a former JAG officer (Army lawyer) who deployed with a combat arms unit in Iraq and made exactly the same kind of targeting decisions that Israeli officers are making today, I’m intimately familiar with the legal complexities of responding to jihadist attacks from built-up urban areas. The process works something like this:

-

Identify the military necessity for the attack. At its easiest, this can mean simply locating the source of gunfire, mortar fire, or rocket fire and attacking the source. It grows more difficult if one is identifying targets that aren’t directly and immediately engaged in combat, like command and control centers, safe houses, or bomb making facilities. It grows harder still when deciding whether to target objects like roads or bridges that have mixed civilian and military use.

-

Make the necessary distinctions between combatants and civilians. One reason why the laws of war require uniforms and other distinctive insignia is to aid combatants in distinguishing between military and civilian targets and thus to minimize civilian casualties. When engaging jihadists who (unlawfully) blend into the civilian population, “distinction” can be the most challenging aspect of complying with the laws of war.

-

Use the proportionate amount of force to achieve the military objective. In practice is this one of the easiest aspects of compliance. A modern military is so well-equipped with precision weapons of varying capabilities that—depending on availability—you can inflict widely varying levels of destruction. But don’t for a minute think a modern military attack is as precise or clean as movies or television pretend. As a general matter, you order up the kind of attack that you know will accomplish your objective.

When I was in Iraq I approved JDAM strikes from B-1Bs and F-16s, rocket strikes from the M270 Multiple Launch Rocket System, Hellfire strikes from Apache helicopters, and many, many artillery strikes from Paladin howitzers. These attacks didn’t violate proportionality rules even though our enemies never possessed equivalent weapons.

Moreover, under the laws of war, once Hamas initiated hostilities against Israel, then Israel possessed the legal right to not just defend itself against Hamas’s attacks or to retaliate against Hamas’s attacks, but to also destroy Hamas as a military force. It merely has to comply with the laws of war if it chooses to do so.

When defenders of Israel cite Israeli “restraint,” this is often what they mean. Not only does Israel comply with the principles above in its targeting policies (and it sometimes even goes beyond the requirements of the law of war by, for example, warning targets of imminent strikes), it refrains from exercising all the force it is legally entitled to use in response to Hamas’s attacks.

While there is a humanitarian element to Israel’s restraint, its restraint is also in its self-interest. Invading Gaza in an effort to wipe out Hamas would result in urban combat not seen since, well, America and its allies used overwhelming firepower to blast ISIS out of Mosul in Iraq and Raqqa in Syria. And if you want to know what even the lawful, proportionate use of force can do to a city when a terrorist army digs in, I’d invite you to look at some of these before and after photos of Mosul after U.S. and allied forces drove ISIS out of the city.

Here’s Southeast Mosul in 2015, before the allied offensive:

Here’s the same area, in July 2017:

That’s what happens when modern weaponry is used in house-to-house fights. It turns cities into the same kind of hellscapes that we’ve seen in newsreels from World War II.

When Hamas volleys rockets at Israeli cities, that creates a legal justification for an outright invasion of Gaza to destroy Hamas. While American arms helped level Mosul with virtually no international outcry, equivalent combat in Gaza would not only create the same kind of humanitarian disaster we saw in Mosul (where likely more than 30,000 people died and upwards of one million were displaced), it would then leave Israel with the obligation of governing a shattered city full of likely radicalized inhabitants.

Any discussion of the law of war often sounds cold and clinical, even though we’re discussing matters of life and death, including the inevitable and tragic deaths of civilians who always suffer when wars rage in city centers—especially when jihadists wear civilian clothes and embed themselves in civilian structures. When Hamas does so, it violates the law of war by inhibiting the distinction between civilian and military targets. The legal and moral responsibility for resulting civilian deaths rests with Hamas, not Israel.

One does not have to view Israel through rose-colored glasses to know that it is right to respond to jihadist attacks with military force, and if one believes that Israel’s response somehow violates the laws and norms of international conflict, it makes me wonder about their knowledge of those laws and norms. Israel is not a perfect nation, but it does have the right to use its superior firepower to attack and destroy jihadists who possess murderous intent.

One last thing …

I’m still a little bit surprised that the Battle of Mosul occurred with so little domestic or international attention. It was arguably more intense than the Battle of Fallujah in 2008 during Operation Iraqi Freedom or the Battle of Huế during the Tet Offensive in Vietnam. The best book I’ve read about the fight is They Will Have to Die Now: Mosul and the Fall of the Caliphate by James Verini. And this, from Britain’s Channel 4, is one of the better documentaries about the battle. Warning. It’s tough to watch, and it illustrates why no one in the world should want a similar fight in Gaza.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.