Let me start with a brief story about a nearly lost man and the simple thing that saved him. Three years ago I was on the road for work, and I was picked up at the airport by a young guy who looked like a vet. We had a ninety-minute trip to the speaking venue, and so we struck up a conversation. I asked him if he served. He said yes. I asked him if he deployed. He said yes, to Afghanistan. I asked how he was fitting in after he came back home.

He got quiet for a moment. He said, “Have you heard of Jordan Peterson?” I said yes, absolutely. In fact, I’d just reviewed his book for National Review. “Well, Jordan Peterson saved my life.”

How? The story begins the way a lot of veterans’ stories begin. After he came back from war, he felt lost. He had no purpose. In a flash he’d gone from an existence where every day mattered and every day had a mission to a world that seemed empty and aimless by comparison. To put it in the words of a cavalry officer I served with in Iraq, “I wonder if I’ve done the most significant thing I’ll ever do by the time I’m 25 years old.”

The young man I was talking to had no mission. He also had no mentor. He picked up the bottle so much that he couldn’t put it down. Eventually he had suicidal thoughts. How did Jordan Peterson bring him back? He told him to clean up his room. Yep, clean up his room. He told him to get organized. He told him to stop saying things that aren’t true.

It all sounds so simple, so basic. Don’t we need transcendent truths to turn our lives around? Well, yes. But sometimes the process starts with direction and with discipline. Especially for young men. The small disciplines led to larger disciplines. Small purpose led to bigger purpose. And there was my new friend—working hard, in a relationship, and saving for a down payment on a house.

No wonder he was choked up with gratitude.

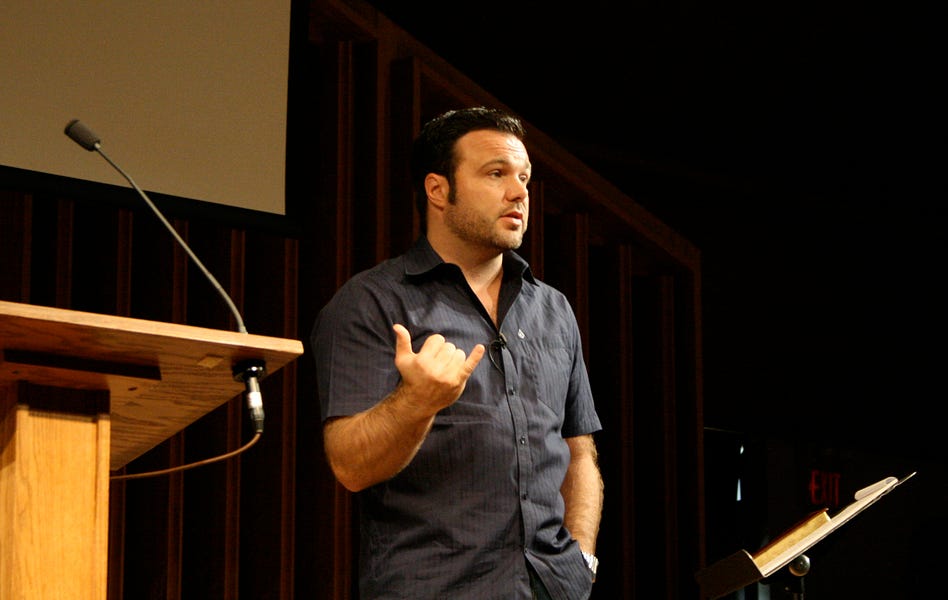

Why bring up that story? Because of one of the most remarkable podcasts I’ve ever heard. It’s by Mike Cosper at Christianity Today, and it chronicles the rise and fall of Mars Hill church in Seattle and the corresponding rise and fall of its celebrity pastor, Mark Driscoll. The thing that’s remarkable about the podcast is that it spends as much time describing what worked about Mars Hill—why Driscoll and his church became a sensation—as it does describing why it failed.

And we can’t start talking about either what worked or what failed without talking about young men like the driver in the story above. Driscoll, you see, was a Jordan Peterson figure before Jordan Peterson. He was a Christian celebrity pastor who understood that many millions of young men were lost. He aimed his ministry straight at them, provided them with a unique version of a boot camp Christian experience (he’d sometimes browbeat the men in his congregation for hours at a time), but then ultimately burned up his credibility in the bonfire of his own arrogance.

Driscoll resigned from Mars Hill in 2014, under fire for his harsh, “domineering” leadership and almost a year after Driscoll apologized for “mistakes” following plagiarism allegations. Mars Hill Church dissolved shortly thereafter.

It’s a story worth remembering, because young men are still struggling with modern masculinity, the church is still struggling to reach them, and Driscoll’s story is one part guide and one part cautionary tale.

I use the word “guide” advisedly, with full knowledge of Driscoll’s deep flaws. But he did see something. He did understand that young men were flailing. They’re still flailing. Here’s how I phrased their predicament in my review of Peterson’s book:

They’re deeply suspicious of organized religion, yet they can’t escape the nagging need for transcendence in their lives. They want answers to great questions, but they’re suspicious of authority. They want purpose, but they don’t know what purpose means apart from careerism. Oh, and all but the most politically correct are keenly aware that mankind is fallen, that men and women are different, and that, while the post-Christian West has allegedly killed God, it can’t seem to replace him with anything better.

This is the landscape of spiraling rates of anxiety and depression, of extended adolescence, and of a generation of young men who’ve been told that masculinity is “toxic” but not taught how to live in a way that recognizes or even cares to comprehend their true nature.

Driscoll stepped into this void with key insights—that men need male mentors (that’s one of the reasons why boys often respond worse than girls to absent fathers), that men often react quite well to direct and confrontational challenges to their manhood, and that men shouldn’t be ashamed that they are strong and often full of competitive fire.

So when Driscoll walked into Seattle life and directly challenged men to get a job, to stop watching porn, to stop sleeping around, and to start supporting a family, It worked for much the same reason the Peterson message resonated a decade later. He gave men a sense of virtuous masculine purpose. Shape up. Protect and provide.

In fact, I joined legions of other Christians in appreciating Driscoll’s message to men. I excused and rationalized some of his excesses, believing he was doing good work challenging men to lead better, more responsible lives.

(I fully recognize, by the way, men are not all the same. They don’t all respond to the same kinds of appeals. The Driscoll blunt approach can repel as well as attract. But it attracted hundreds, then thousands, then tens of thousands, then hundreds of thousands of young Christian men as Driscoll’s star kept rising.)

But Driscoll ultimately failed. My appreciation was ultimately mistaken, and I’ve tried to learn from my own failure of judgment. Even worse, Driscoll didn’t just fail as an individual, the way so many celebrity pastors fail; his philosophy and approach failed the men and the women in his church. It caused great harm. And it’s worth exploring briefly why—because the “why” also applies to multiple modern Christian efforts to reach young men.

One of the core reasons for the Driscoll failure (and for other failures before or since) is that he met a cultural overreaction with an overreaction all his own. He opposed a specific secular extremism with a Christian extremism that ultimately proved his critics correct.

I’ve written a considerable amount about the secular war against so-called “toxic masculinity,” and while I recognize that toxic masculinity does exist, its definition often sweeps way too broadly. As I wrote in one of my first Sunday French Press essays, the American Psychological Association’s 2019 declaration that “traditional masculinity—marked by stoicism, competitiveness, dominance, and aggression—is, on the whole, harmful” represented a formal manifestation of a misguided cultural trend.

Look at the list of characteristics above. Aside from “dominance,” the characteristics above can be vices or virtues depending on the context. Stoicism can be harmful, yes, but (as I’ve argued before) it can be indispensable to helping a man “navigate the storms of life with a calm, steady hand.”

Aggression seems like a vice, right up until the moment when you need a good man to stop an evil man in his tracks. A competitive spirit can be harmful, but it can also build companies, institutions, and even nations. It can inspire extraordinary innovation.

No, you don’t want to jam any person into the masculine stereotype and demand that they exhibit the characteristics above, but when those characteristics are present—and they are in many, many men—the challenge is to channel them into virtue, temper them away from excess, and ultimately subordinate them to the way of the cross.

So what’s the Driscoll sin? What’s the common mistake of so many efforts to celebrate Christian masculinity? It’s to functionally take the exact opposite approach of the APA—instead of treating these characteristics as inherent vices, the Driscolls of the world turn them into inherent virtues. They glory in aggression, competitiveness, and achievement.

The end result was a theology that conformed Christianity to traditional masculinity rather than conformed masculinity to Christianity. A theology and community that focused on sex differences created a world in which masculinity and male power was central to the identity of the church and the movement.

The most heartbreaking of the podcasts so far was Episode Five, entitled “The Things We Do to Women.” It discusses how the church’s extreme focus on empowering men and fostering a “biblical” masculinity resulted in a culture that subordinated women to such a degree that wives were often treated as playthings for their husbands—encouraged to strip for them and perform sex acts that they found deeply uncomfortable and degrading.

But the “smoking hot wife” was the reward for the godly man, and satisfaction of his insatiable sex drive was his entitlement.

And thus you see the depravity of a thinly Christianized version of true toxic masculinity. What was first a church that challenged men to restrain their vices (Stop sleeping around! Stop watching porn!) ending up indulging men in modified versions of those same vices (You can still have all the sex you want! Your wife is your porn!) At the end of the day, the Driscoll example for young men was dangerous—he sent a message that with daring and discipline, you could become not just a responsible man, but a dominant man.

Thus, perversely enough, Driscoll sanctified a secular version of masculine toughness and virility. The (sometimes necessary) act of grabbing men by their metaphorical lapels and shaking them out of their stupor ultimately pointed them away from the cross and towards the same will to power that has bedeviled mankind since the Fall.

Let’s return to the young vet at the start of the essay. Like Driscoll did to young men a decade before, Peterson woke him up. He gave him a sense of immediate purpose. He spoke to a man in the way that so many men understand—directly, challenging them to do better, to be better. These kinds of direct challenges, whether they come from dads, pastors, authors, coaches, or drill sergeants, can be immensely valuable. Sometimes they’re the only thing that can reach a man’s heart.

When you can understand this reality, you can start to see Driscoll’s appeal. His ministry did change lives. Others like him—before and since—have changed lives. And when you change a man’s life, you can inspire fierce devotion.

But pastors and leaders must handle that devotion with great care. When countering a culture that often attacks traditional masculine inclinations as inherent vice, the answer isn’t to indulge traditional masculine inclinations as inherent virtue.

In fact, in our efforts to define what it means to be a Christian man, we shouldn’t center our efforts on “masculinity” at all, but rather on understanding a person—a person who, “though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross.”

Driscoll, in all his toughness and swagger, tried to make men out of Christians. The church, however, should make Christians out of men.

One last thing …

The Mars Hill podcast also reminded me of this marvelous song by Sandra McCracken. We had the pleasure of hosting her in our home a few years ago, in a setting very much like this. Sandra is talented and a thoughtful, delightful person as well. I hope you enjoy this song as much as we did:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.