Before I dive into the substance of this newsletter, I want to thank all of the members who wrote me kind notes. Where were my newsletters? I went on my first vacation in five years, and forgot to tell you I was going! My college friends and I took a cross-country RV trip to Leadville, Colorado, and, among other adventures, we hiked up Mount Elbert, the highest peak in Colorado. We replicated a trip we took 28 years ago, and—much to my surprise—I found out I could still make it up the mountain. I’m ridiculously sore, but my typing fingers are healthy. So, to quote Jonah, “I’m back.”

Now let’s talk about riots.

One of my persistent frustrations about our national political conversation is that we consistently act as if hard things are easy. The examples are legion, but let’s focus on the most salient issue of the last month—urban unrest. Here we have two competing promises from two competing presidential candidates. First, here’s President Trump declaring that he could solve the problem of urban unrest in Portland “in approximately one hour.”

Joe Biden is less bombastic, but here he is pledging to be a president who will “stop violence—not incite it.”

But let’s take a closer look at urban unrest and why I’ve said that quelling unrest is one of the most difficult jobs in all of politics and policing. External critics of city, state, and national governments often treat the challenge as if there’s an on/off switch. Good mayors can turn it off. Bad mayors leave it on. Good presidents stop violence. Bad presidents watch cities burn.

Make no mistake, leadership matters. It truly does. Bad leaders can incite violence. Bad leaders can blunder into chaos. But it’s worth pondering why a city can spiral out of control and why it can be so hard to not just end riots, but restore true stability and peace.

Let’s start with a simple proposition. Riots and unrest don’t spring forth from healthy communities. Think of a riot as a symptom that makes a disease worse—in the way that a horrible hacking cough can break a rib. It doesn’t justify riots to say that they don’t typically occur absent systemic injustice, but it is an explanation, and without resolving systemic injustice, tamping down any given riot doesn’t resolve a crisis, it often merely postpones the next reckoning.

For example, conservatives who remember the Ferguson riots mainly remember the Ferguson hoax—the claim that Michael Brown was shot dead with his hands up, in a posture of surrender. In fact, as the Obama Department of Justice found, the best evidence indicated he died charging officer Darren Wilson, after he’d already attacked Wilson and tried to take his gun.

But we often forget the second Ferguson report, which found a pre-existing “pattern and practice” of unconstitutional conduct from Ferguson police and that the police engaged in systematic policing-for-profit that resulted in police focusing on revenue generation rather than personal safety, thus using the city’s poor citizens as virtual ATMs, draining them of necessary cash to fill municipal coffers.

Ferguson is not unique—most Americans don’t realize this sad fact, but many American communities exist as virtual municipal kindling, awaiting on the spark (whether it comes from a hoax, rumor, or genuine atrocity) that will ignite the flame.

Second, in most instances, rioters are outside of—and defy—conventional partisan control. Yes, there are violent men and women who are obviously and clearly on Team Red or Team Blue—think, for example, of the “Trump trucks” that barreled through Portland last weekend, pelting leftist activists with paint and pepper spray. But when it comes to riots, “left” or “right” does not necessarily mean “Democrat” or “Republican,” and thus they’re explicitly outside any form of partisan influence or partisan control.

I’ve heard Republican partisans describe rioters in Portland or Seattle as “Biden’s base.” As a general matter, this isn’t just wrong, it’s laughably wrong. Many of these rioters don’t see a dime’s worth of difference between Biden and Trump and instead seek revolutionary change entirely outside the conventional electoral process. They see the entire American system as bankrupt, and don’t exist as reformers, but rather as destroyers. They see themselves as revolutionaries. Tell them they’re helping Trump (or Biden) and they just don’t care.

And don’t forget, the first round of Black Lives Matters protests flared during the Obama administration (this was part of the “American carnage” Trump condemned). There were violent uprisings in Democratic-controlled cities, in Democratic-run states, in a Democratic-governed nation. Even though the formal BLM was and is on the left, its violent elements were indifferent to partisan political needs.

Thus, with the exception of the few explicit partisans (again, think Trump’s trucks), political condemnations of violence and rioting serve mainly as reassurance to non-rioters rather than as a deterrent against the riots themselves. They communicate that a politician aims to quell violence rather than seeks to rationalize chaos. They do virtually nothing to defeat the violence itself.

Third, improperly applied force can make violence worse. This is one of the most important principles of riot control. There is no formula that declares, “More force equals more control.” In fact, the potential for excessive force to create chaos is so well-known that it’s often the aim of rioters to trigger a violent police or military response. They want the tear gas to fly. They want to see the broadside of rubber bullets.

Think of it like this—if a hard-left protester believes that America is violent and corrupt (bordering on fascist), then one way to make their case is to trigger or provoke a “fascist” response. Thus, taunting of police is omnipresent, low-level violence (like throwing bottles or launching fireworks) is constant, and the fervent hope is for a police overreaction.

And make no mistake, police overreactions and excessive force can provoke more violence. Famously, the dramatic, quasi-military police response to the first flare-up of violence in Ferguson helped fuel further unrest. When the Trump administration forcefully cleared Lafayette Square before his Bible photo-op, it triggered a dramatic backlash. In Portland, it was one thing to deploy federal officials in a defensive posture around federal buildings, it was another thing entirely to send cops in military-style uniforms to grab suspects off the streets and stuff them in unmarked vans. The response was volcanic.

Fourth, a permissive law enforcement approach can also make violence worse. It would certainly be nice if there was a passive, limited law-enforcement approach that could reliably contain and quell urban unrest. And there are times when it seems that cities long for the passive approach to work – contain the violence, let it run its (hopefully short) course, clean up, and move on with life. Above all, don’t permit your police response to give activists additional fuel for their fire.

While there are many examples of the failure of passive policing, I can give one that’s obvious and recent: Seattle’s CHAZ, its Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone. Police essentially ceded control of a small portion of the city to a mixed group of violent and nonviolent protesters, and it turned out that the occupation wasn’t short, the violence wasn’t contained, and there was no opportunity to clean up and move on with life until the area was cleared.

Moreover, the passive policing that has frequently followed public controversy and violent riots often results in persistent increases in violent crime. The result is a complex nightmare for public officials. Earlier today, The Atlantic and ProPublica released a comprehensive report on the challenges of “underpolicing” in the aftermath of urban unrest. I’d urge you to read the entire thing, but this section captures the complexities nicely:

For decades, it was political death to run afoul of the police and their powerful unions. Now the electorates of many cities have shifted further left and grown more vociferous about demanding police reform and even defunding departments, which puts more pressure on elected leaders to take a tougher stand against their departments than they might have in years past.

That means big-city mayors including Atlanta’s Keisha Lance Bottoms, New York’s Bill de Blasio, and Chicago’s Lori Lightfoot face a daunting challenge. They have to navigate two problems at the same time: reining in overpolicing while also preventing underpolicing, the consequences of which are every bit as dire. And a great many lives are riding on how well they pull that off.

Fifth, local popular sympathy for riots can complicate the law enforcement response immensely. It’s a simple fact that the hard left exerts more political influence and control in Portland than, say, Nashville. For example, read this excerpt from a New York Times article profiling new Multnomah County District Attorney Mike Schmidt:

The new prosecutor, Mike Schmidt, took office Aug. 1 after overwhelmingly defeating an experienced federal prosecutor in Multnomah County, which includes most of Portland. Even his critics say the breadth of his victory gave him a mandate to reshape prosecutions in Portland, a city of frequent protests, where there is no clear end in sight to demonstrations against police brutality that began after the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

He has not been slow to shake things up: Ten days after taking office, Mr. Schmidt effectively dismissed charges against more than half of about 600 people arrested since the protests began at the end of May.

Note the word “overwhelming.” This is the prosecutor the citizens wanted, a man who immediately dismissed charges against most arrested rioters. Perhaps Portland is ready for a crackdown now, but by its votes the city wasn’t ready for a crackdown yet—in spite of not just weeks, but years of political violence in its streets.

This newsletter is running long, but I’ve barely scratched the surface of the complexity of the challenge of urban unrest. Governing a fractured, divided, and restless nation is hard, and the demand that we make it simple—that we “crack down” or, conversely, “defund the police” only make the challenge more difficult. Crack down too hard, and you fuel the fire. Create power vacuums and you cede control of entire city blocks to a community’s worst elements.

One of the casualties of American polarization is that we’ve placed a much greater premium on partisanship than governance. Competence is not a value that wins many elections. But it’s past time for a bipartisan backlash against rhetoric and in favor of results. As we move past 2020, I know one way I’ll identify rising stars (from either political party). I’m going to ask a simple question: When the immense challenges of 2020 rocked their cities and states, how did they respond?

Did they have the rare wisdom that enabled them to use force when it was necessary, to back off when it was prudent, and to understand at all times that they are dealing with communities that are often deeply hurting after decades of poor governance and sometimes centuries of injustice? Or did they fall back on platitudes, cast themselves as victims, and bluster their way through the crisis?

But this much we know: Our nation faces a crisis, one that’s likely to get worse before it gets better, and it’s past time for the American public to understand that deep challenges defy easy answers. It’s time for the American public to expect more from the men and women they choose to lead.

One last thing …

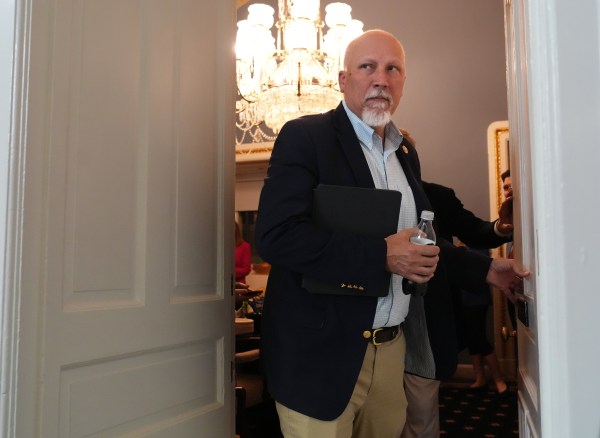

Not everything is bleak. Heroes do rise. For example, this man—a man who stood before the leaders of his city and spoke truth to power. Who is he? I do not know. Is he conservative? Liberal? I do not know. But he’s a man for the moment, and through his words, a fractured nation can unite:

Photograph by Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.