Hey,

I’m not in a very punditty (pundesque? Pundit-like?) mood. So I’m just gonna take a weird route to something I want to get off my chest.

Earlier this week, partly inspired by Scott Lincicome’s excellent newsletter (which is an actual newsletter, and not a “news”letter), I wrote about the effort to make vaccine development into a nationalistic issue. I wrote:

There’s plenty of room for the U.S. to chest-thump about its role in the record-pace rollout of these vaccines. But it’s worth keeping in mind that this was a group project on a global scale, and without the benefits of that global scale, we’d surely be waiting a lot longer.

Basically, this is an “I, Pencil” point. Leonard Read, writing from the perspective of the pencil, noted that these writing devices are wondrously simple, portable, reliable and inexpensive, “Yet, not a single person on the face of this earth knows how to make me.”

Pencil manufacturers know how to complete only the last steps of a process that begins in distant forests, mines, and factories. There are lots of lessons from Read’s essay: The market is a wondrous invention that allows people of different faiths, nationalities, ideologies, etc., to work peacefully and cooperatively with each other, literally all around the globe. Another is that some knowledge is cumulative. Every generation, human nature might start back at zero, but technical knowledge advances, because it is transmitted through physical things and through institutions. If, every generation, we had to relearn from scratch how to make a pencil, never mind a microchip, we’d never invent either. One additional lesson is that the division of labor is the great engine of productivity. Other people made all these points before Read, but if I wanted to introduce high school kids to the glories of the market, I wouldn’t have them read about pin factories in The Wealth of Nations—I’d have them read about the humble pencil.

But let’s move on from pencils to shoes. In 1973, Murray Rothbard—a brilliant intellectual, but very much a mixed bag ethically—published his Libertarian Manifesto in which he described the “Fable of the Shoes.”

In the fable, Rothbard railed against “status quo bias.” In the world outside of government, “New products, new life styles, new ideas are often embraced eagerly.” But when it comes to the government, people are very stubborn. The government is supposed to pay for police, firemen, retirement, and whatever else, and any suggestion otherwise strikes some as offensive. “So identified has the State become in the public mind with the provision of these services,” Rothbard laments, “that an attack on State financing appears to many people as an attack on the service itself.”

Imagine, Rothbard writes, that people had always gotten their shoes from the government. Then, imagine someone proposed privatizing the production of shoes:

He would undoubtedly be treated as follows: people would cry, “How could you? You are opposed to the public, and to poor people, wearing shoes! And who would supply shoes to the public if the government got out of the business? Tell us that! Be constructive! It’s easy to be negative and smart-alecky about government; but tell us who would supply shoes? Which people? How many shoe stores would be available in each city and town? How would the shoe firms be capitalized? How many brands would there be? What material would they use? What lasts? What would be the pricing arrangements for shoes? Wouldn’t regulation of the shoe industry be needed to see to it that the product is sound? And who would supply the poor with shoes? Suppose a poor person didn’t have the money to buy a pair?”

Now, I’m not the privatizer Rothbard was. I think privatizing the police—which, by the way, would be the inevitable consequence of defunding them—is a bad idea. But beyond that, I think most questions about whether the government should be involved in an activity is a prudential one. Everyone wants the garbage collected; only very strange people think it’s vitally important that the government do the collecting. The military needs fighter jets. I don’t know why anyone thinks it would be better if the government made them rather than just bought them.

What government is for.

This is my basic attitude toward almost everything the government does. There’s an old saw about how to sculpt an elephant: Take a block of stone and remove everything that doesn’t look like an elephant. (The first time I encountered this saying it was attributed to Rodin, but, apparently, it’s one of those quotes lots of people and nobody ever said). That’s how I think about government. It’s a provider of services. What services it should provide is a question best explored with cost-benefit analysis and pragmatism—not poetry, spiritualism, or religion. I’m not saying there’s no room whatsoever for such considerations, but if you remove everything that doesn’t look like an elephant you’ll find only a handful of things that survive such editing. And most of the things that do are symbolic or rhetorical. That doesn’t make them unimportant. In fact, because they pass that test, they are very important because they speak to what this country is about and what makes it special.

For instance, the Supreme Court’s decision to reject the vile and inane Texas lawsuit is not something that could come from a private entity. The fact that the Supreme Court is the last branch of government to take the Constitution seriously may be lamentable, but its seriousness is something to celebrate—and encourage, given that there’s no reason to think it can’t surrender to the same corruption afflicting the other branches.

For most of my professional life, I’ve focused on the way the left rejects my kind of thinking about government. “Government is just the word for the things we do together,” “let us commit to a cause greater than ourselves,” and other bromides tend to fall under what the New Deal legal theorist Thurman Arnold called a “religion of government.” In The Folklore of Capitalism, Arnold proposed the adoption of such a religion “which permits us to face frankly the psychological factors inherent to the development of organizations with public responsibility.” That might sound fine on the surface, except that in his view this new religion should authorize massive expansion of the government’s role in society and the economy. Arnold was just one of countless progressive intellectuals who railed against America’s “ritualistic” attachment to free enterprise, competition, individualism, and other “atomizing” ideas that had outlived their utility.

Which reminds me: I’d have a lot more respect for the new nationalists if they stopped acting as if they just discovered ideas that were old a century ago. The hallucinatory notion that libertarians have been running Washington for the last 30 years is precisely the sort of thing the progressives of the Wilson-Roosevelt era believed. And at least they had some evidence to back up their view.

Government can’t love you.

And that brings me to my point, or at least one of them. The desire to imbue government with religious significance isn’t just a progressive trope, it’s a human one. The separation of politics and religion is unnatural. For most of human history—and all of prehistory—such a distinction would have seemed bizarre. Jesus’ call to render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s and unto God what is God’s was a deeply radical break with the past. When the Western Roman Empire collapsed, political authority moved to Constantinople, but Christian religious authority stayed in Rome. This was the beginning of a very long process of creating space between the secular and the religious, or what St. Augustine called the City of Man and the City of God. Augustine’s cities weren’t geographic places but spiritual places inhabited by individuals who lived side-by-side with each other. This evolution eventually led to the Peace of Westphalia which ended Europe’s religious wars. This helped to establish freedom of conscience, because exhausted Europeans finally, in the words of C. V. Wedgwood, recognized the “essential futility of putting the beliefs of the mind to the judgment of the sword.”

Michael Burleigh argued that the wars of religion didn’t really end so much as take on new ideological forms. But that’s a discussion for another day.

The Founding Fathers knew this history. They recognized the dangers of melding politics and religion, though they were as concerned about the peril for religion as they were for politics. Lots of conservatives never knew or cared about this history. But like the pencil manufacturer who doesn’t know how to make pencils, they accepted as a matter of dogma the result of this long process.

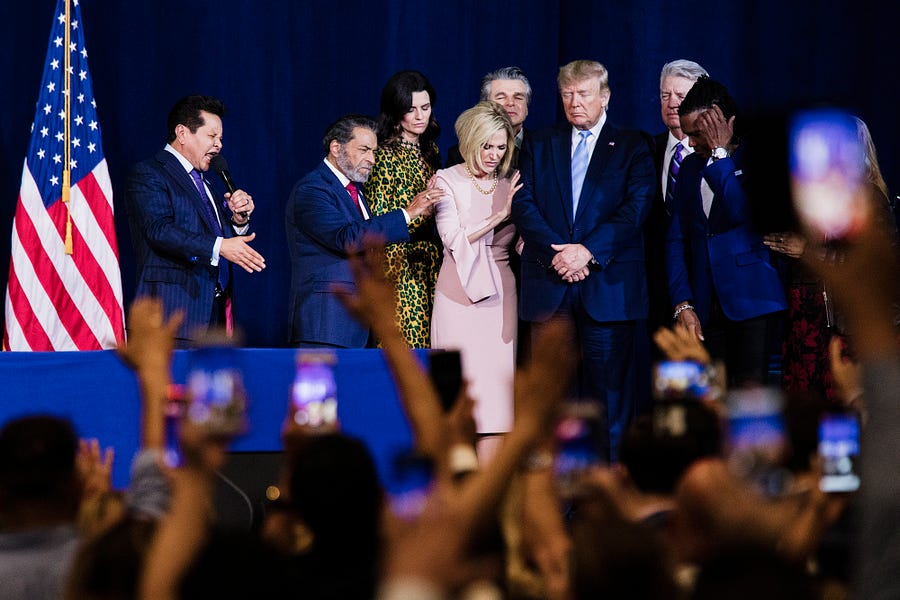

But one of the most remarkable things about the last five years is how brittle and fragile that dogma proved to be. In the comparative blink of an eye, many conservatives have embraced their very own version of a religion of government. But it’s not like Arnold’s or even Auguste Comte’s, which at least put government in a role above partisan politics. This is a religious heresy that centers around, of all people, Donald Trump. The phrase “cult of personality” may have its origins in Marx and, later, Soviet de-Stalinization, but it’s the right term for what we are seeing. Because it is a cult centered around a single, profoundly unbiblical, unspiritual, ungodly and, I am perfectly comfortable saying, un-Christian personality.

I won’t recycle David French’s excellent exploration of the idolatry at the heart of all this. But whether you’re the My Pillow dude or a guy wandering the bus station in sackcloth, if you claim to have a vision that tells you that Donald Trump is God’s anointed emissary on this earth and that you should die in an effort to steal a second term for him, it’s a safe bet you’re dealing in false prophecy. And if you think God’s will was foiled not by Hugo Chavez and George Soros, but by demons, you’re gonna have to show your work.

One of the things I learned from Julien Benda’s The Treason of the Intellectuals was how to spot a certain “tell” to spot spiritual and political corruption. If you claim Jesus as the exemplar of your worldly, ideological cause, you are telegraphing either political or spiritual corruption.

Now I don’t mean that, say, opponents of abortion or capital punishment are wrong to invoke Jesus and his teachings. That strikes me as a valid and defensible effort to live up to Jesus’ principles as you see them. What I mean is the sort of thing Benda chronicled at the beginning of the 20th century. Ideological protagonists would claim that “Jesus was the first nationalist,” or “Jesus was the first eugenicist,” or “Jesus was the first socialist.” This sort of thing was all over the place in Europe and America. The social gospel progressives spouted this stuff constantly. And yes, later opponents of the New Deal played a similar game.

Very few people are flatly saying Trump is like Jesus (though thanks to Google you can find examples). What they are saying, all over the place, is that Trump is the fulfillment of Christian prophecy or some similar nonsense. They’re literally putting Jesus in a MAGA hat.

I’ll put it this way: I have all the respect in the world for people who believe Donald Trump should behave more like Jesus. I am a total loss as to how people can want Jesus to be more like Trump.

This isn’t upholding a Christian principle. It’s not even enlisting Jesus to a secular political cause—which lots of people do, rightly and wrongly. It’s claiming that the person you hold to be the Son of God and the Messiah was really an activist for your very worldly cause which divides people into good and bad—not because they reject scripture, but because they reject your very worldly political ambitions or, in this case, your idolatrous infatuation with Trump. Eric Metaxas (who became famous for his book on Dietrich Bonhoeffer of all people) is now saying that the people who refuse to think a made-up conspiracy theory about the election being stolen “are the Germans that looked the other way when Hitler was preparing to do what he was preparing to do. Unfortunately, I don’t see how you can see it any other way.”

And that’s the problem in a nutshell. We spent two 2,000 years working toward an idea of government that American conservatives are charged with conserving. But for some reason that should all go out the window, because one fallen man is the Chosen One—the fact that he wasn’t chosen by the voters be damned.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.