Hey,

I know Martin Luther King Jr. Day is behind us, but I’ll start there.

I heard a segment on NPR’s All Things Considered exploring a very old complaint on the left: People are paying short shrift to Martin Luther King’s more radical positions.

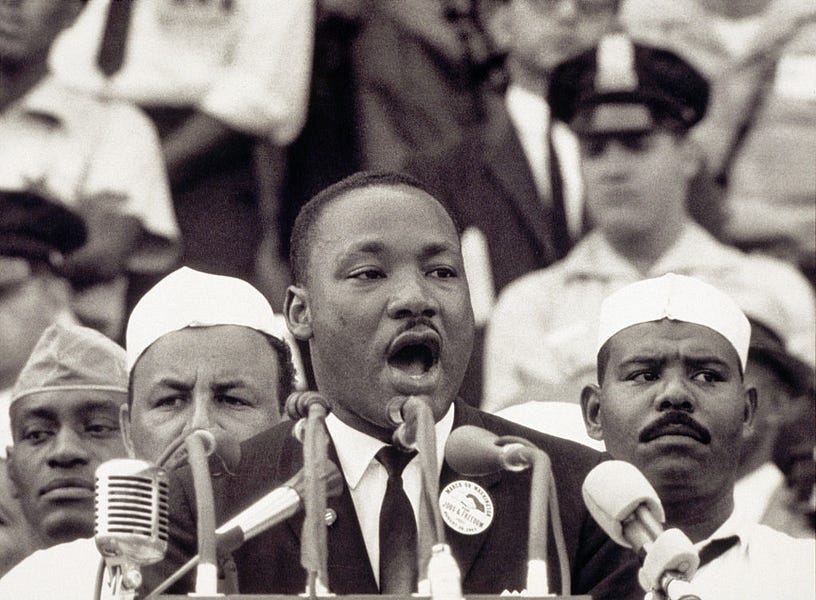

During the broadcast, probably the most famous line from King’s “I Have A Dream” speech was played:

My four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.

The correspondent, Adam Florido, had this to say: “That quote is often used to suggest King would support a conservative vision of a colorblind society, in which policies like affirmative action or voter protection laws are unnecessary.”

One strange thing about the rest of the piece is that neither Florido nor the people he talked to offer any evidence that King would not agree with a colorblind vision of society. Florido also doesn’t provide anything to back up the claim that the people quoting King’s colorblind quote actually believe that “voter protection laws are unnecessary.” I quote that line all the time, and I think voter protection laws are necessary. If the argument is that the laws currently being pushed by Democrats are necessary, that’s fine. But I take serious exception to the insinuation that if I oppose the John Lewis or For the People Acts then I’m against voter protection laws per se. I’m fine with the Voting Rights Act 1965 staying the law of the land. And as Bob Driscoll noted in a great piece for us on Monday, it’s not going anywhere. This is an important point, because I’ve heard countless talking heads conflate reauthorization of the preclearance stuff with reauthorization of the act itself. The Voting Rights Act doesn’t require reauthorization because it’s the law, and no one is proposing getting rid of it.

But I want to circle back to what Martin Luther King Jr. believed. I have no idea if he’d be in favor of the Democrats’ proposed reforms, but I’m happy to concede that he’d probably favor them. I’m also convinced that he’d favor affirmative action. Interestingly, while I’ve been hearing for years that King’s more radical vision on economics needs to be promoted and respected, I hear far less often that his views on the centrality of religion should be given equal respect.

That said, it’s worth at least acknowledging that in his truly historic and glorious speech that moved so many hearts and minds toward the cause of civil rights, he didn’t make the case for affirmative action. That matters. King was no fool. He understood that he was engaged in the political project of persuading Americans not just of the rightness of his appeal but of the Americanness of it. The best and most important passage of his “I Have a Dream” speech was the part that explicitly tied his cause to Abraham Lincoln’s. Forgive the lengthy excerpt:

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the “unalienable Rights” of “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.”

The genius of this argument is that it expands on the genius of Lincoln’s argument in the Gettysburg Address. Lincoln turned the Declaration of Independence on its head, making the preamble the most important part of the document. King embraced Lincoln’s standard, held it up to the American people, and asked: Are you living up to it?

King may have had all manner of socialist (social democratic, to be more fair and accurate) views. But the argument he chose to make before the court of public opinion did not obviously draw on those views or intellectual traditions. Instead, he told Americans that they were not living up to their own highest ideals; they were falling short of the story we tell ourselves about ourselves.

It was as politically brilliant as it was rhetorically powerful. And it is absolutely fair—I would argue it is right and just—for conservatives to invoke those words, since it was those words that moved all manner of Americans to back King’s cause.

I get the desire to sanctify King and I get the desire of more radical activists and intellectuals to leverage his stature to smuggle more of his views on economics and foreign policy into the mainstream. But I don’t see why I’m obliged to let the effort go uncontested. Abraham Lincoln, the Founding Fathers, Albert Einstein, Mahatma Gandhi, Calvin Coolidge, H.L. Mencken, George Orwell, and—let me save everybody some time—every other famous or great person in human history held some opinions I think were wrong. I don’t have any obligation to change my opinion about what they got wrong just because they were right about the things that made them great. To take just one example, Gandhi was a great apologist for Hitler’s aggression. He was also obsessed with bowel movements and championed celibacy. I feel no reluctance in saying he was wrong about these things regardless of what he was right about.

There’s a funny irony here. Opponents of King would often point to his radicalism on economics or his marital infidelity to discredit his views on civil rights. In response to these attacks, defenders of King’s and of civil rights generally made the same argument I’m making in this “news”letter: There is no transitive property at work here. Think of it this way. Sen. William Fulbright was a segregationist who joined the filibuster against the 1964 Civil Rights Act. He also broadly agreed with Martin Luther King Jr. about Vietnam. I very much doubt the people who want to lionize all of King’s views think that Fulbright was less wrong about civil rights just because he shared King’s opposition to the war in Vietnam.

Politics isn’t religion, no matter how hard some try to make it otherwise. I gather that Christians are supposed to agree with Jesus on everything—even if many fall short—because Jesus was the Son of God or God in human form. I’m not mocking. I just don’t have the best handle on the trinity. Everybody else is just a human and humans are rarely right about everything. In a democracy, what matters most are the arguments people make and the ideas they promote.

One last thing. Whenever important historical figures die, a kind of transmutation process begins. Their legacy becomes departisanized (yes, I made that word up). It happens across the ideological spectrum, but I’m most familiar with it for conservatives. Barry Goldwater, William F. Buckley Jr., Ronald Reagan, and even George H.W. Bush were all reviled by many on the left, but their reputations were rehabilitated postmortem to use them as cudgels against the right (I can quote you chapter and verse on this for days). But again, it happens with liberals, too. There’s a niche cottage industry dedicated to recasting JFK as a conservative (and they make some good points), and there are still plenty of conservatives with lots of nice things to say about FDR (they make fewer good points).

The only thing I know for sure is that if Martin Luther King Jr. were alive today, he’d be 93. Everything else is an argument.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.