Hey,

One of the great errors in political thinking is mistaking bad excess with bad categories.

At first blush this is just a fancy way of rephrasing one of the least profound insights one can offer: Don’t let a few bad apples lead to defunding the police, the FBI, whatever. Don’t let a few racist white people drive you to blather, “Yes, ALL white people are racist.”

But the bad apple thing is merely one facet of what I’m talking about. People often think that the extreme expression of a concept reveals the “true nature” of a concept. Horrible things are done in the name of nationalism, therefore “true” nationalism is horrible. Terrible things are done in the name of socialism, therefore “true” socialism is terrible. There’s no -ism you can’t do this with. Whether it’s slippery slopeism or the hasty generalization fallacy or a half-dozen other logical fallacies, we have a tendency to think that the plural of anecdote is data, that if A happens Z must inevitably happen, and that the most pure and extreme form of a phenomenon or concept is its truest self.

But let’s put aside logical fallacies and instead concentrate on a logical truism. I’ll call it Paracelsus’ dictum.

Paracelsus (1493-1541), was a German Renaissance philosopher and chemist, considered to be the father of the phrase and concept, “The dose makes the poison.” Or as Paracelsus put it, “What is there that is not poison? All things are poison and nothing is without poison. Solely the dose determines that a thing is not a poison.” I am sure there are some counter-examples. But I think the fact that water and oxygen poisoning are real things proves the point.

Some readers and listeners are probably tired of my “nationalism is like salt” analogy, but I’ll repeat it anyway. Nationalism is like—you guessed it—salt. A little is essential to good cooking, bringing out the flavor. Too much ruins the meal. And way too much is literally toxic.

Given my headline, you can surely see where I’m going next.

Often, when I do my spiel about how the parties are too weak, some well-intentioned, civic-minded, bipedal person tells me I’m wrong. Some respond that the problem isn’t just that the parties are too strong, but that we have parties at all. Others will tell me that partisanship is always bad.

I disagree and I figured I should give another stab at explaining why.

Party hard.

First, what do we mean by parties? The idea of factions is as old as politics. And in most political writing prior to, say, Edmund Burke, that’s what people meant when they referred to parties. Think of phrases like “the war party”—it’s not like little old ladies stuffed envelopes at Cato’s headquarters trying to get people registered for the “War Party.” Indeed, it was Burke as much as anyone to whom we owe the modern idea of parties, rightly understood. He wrote, “Party is a body of men united, for promoting by their joint endeavors the national interest, upon some particular principle in which they are all agreed.” Notice that even here, this definition doesn’t necessarily imply a formal organization that puts up yard signs and spams old people for money.

There are a very small handful of nonpartisan democracies, i.e., countries where they don’t have formal political parties. But with all due respect to Palau and Tuvalu, none of them provide models for a large, advanced, continental nation.

Still, it’s worth noting that the worst possible system isn’t a country with no parties or a country with two or more parties. The worst system is a country with a single party. Because when you have a single party the interests of the party are synonymous with the interests of the state. One-party states are simply aristocracies by another name, where the privileged class uses the power of government to enrich itself.

Simply put, democracy doesn’t work at scale unless you add a competitive element. You need at least one out-group to offer an alternative vision of how to run things. It’s the job of Party A to point out the mistakes of Party B and vice versa. Without Party B, there’s no reliable and durable mechanism for holding Party A accountable. No team sport works without at least one other team.

And no team can win without teamwork. And teamwork is very, very, hard without team spirit. In politics, team spirit is called partisanship.

Partisanship focuses the mind and makes partisans attentive to what the other party is trying to get away with. Partisanship provides an incentive to fact check the government, when the government is run by the other party. You can say that’s the job of the press—and it is. But often that work is done by partisans in the press or the press relies on questions and inconvenient facts raised by partisans.

But partisanship, certainly in the Burkean sense, is what drives elected officials in government to honor their promises and pledges. It provides them with an answer to the question, “What are we supposed to be doing here?”

Let me head you off. When partisanship approaches toxic levels, politicians still ask that question, it’s just that the answer is crappy.

During the so-called “Era of Good Feelings” from 1815-1825, we didn’t have parties and it was a mess. People in the government turned on each other. Factions focused on narrow advantage instead of a greater good. President James Monroe, who disliked parties almost as much as he disliked European meddling in the Western Hemisphere, wrote to James Madison that the lack of political parties sowed chaos in government. “Where there is an open contest with a foreign enemy, or with an internal party … the course is plain & you have something to chear & animate you to action,” he wrote. But without a party to oppose “there is no division of that kind, to rally any persons, together, in support of the admin[istration].”

Functioning parties help politicians rouse enthusiasm, form coalitions, establish clear and coherent goals, and unity of purpose.

Think of it this way. What do you call someone who thinks that today’s high profile congressional hearings are an embarrassing affront to democracy and our collective intelligence?

Someone who watches congressional hearings on C-SPAN.

But now think about what a properly functioning congressional hearing, or even the Platonic ideal of congressional hearings would look like.

It wouldn’t be devoid of partisanship. Rather, it would be marked by a healthy level of partisanship. The Democrats would call witnesses—just like lawyers in a courtroom—that help their case and Republicans would call witnesses that help theirs. Of course, with healthy partisanship at work, legislators would be able to adjust their positions, even change their minds, when the facts or arguments dictated. But good policy, like the truth, is best discovered through argument.

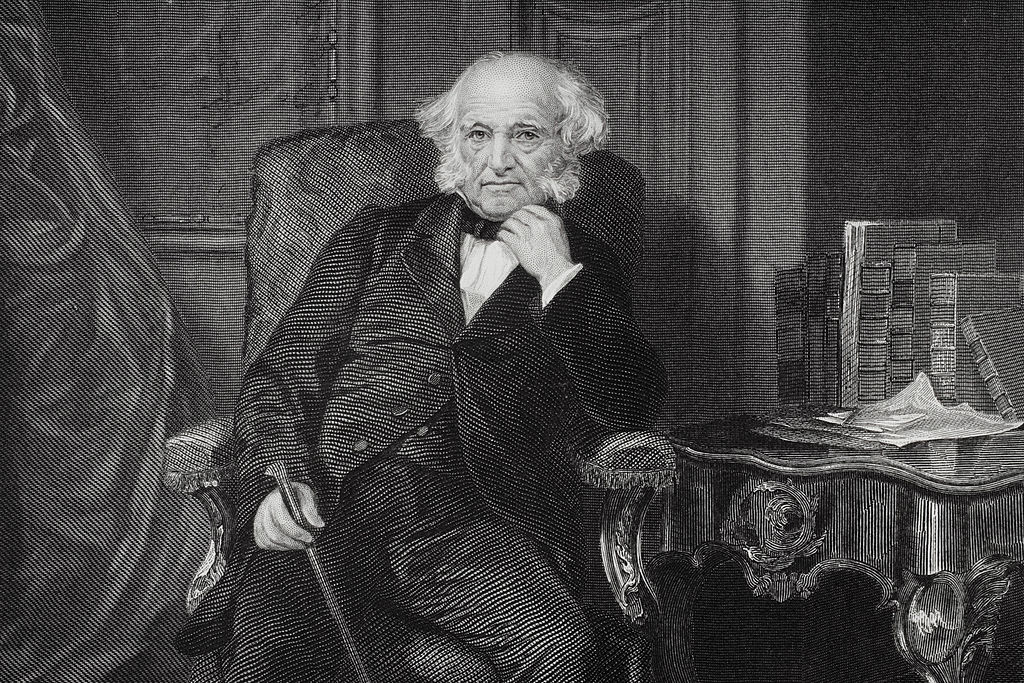

Martin Van Buren, the eighth U.S. president—and inspiration of the Van Buren Boys gang—learned from the folly of the Era of Good feelings and built the foundations of the two-party system. He believed that two national parties would serve as a bulwark against sectarianism and cults of personality overwhelming the American experiment. The Civil War was a blow to the project but not to the principle.

Okay, now let’s talk about journalism.

A lot of journalism is supposed to work the same way. Until the mid-20th century and the fetishization of “objectivity,” journalism was a much more openly partisan affair. That doesn’t mean newspapers were corrupt or dishonest, it’s just that they had an editorial viewpoint that helped frame what they covered and how they covered it. Today, we think “straight news” outlets aren’t supposed to do that. But they do, they just lie about it—to the reader and to themselves.

This is one of the reasons why I like opinion journalism so much. Openly partisan journalists are good for democracy, so long they are honest about their priors and are consistent about their principles. If you change your principles for purely partisan reasons, you’re simply doing party work by proxy. Magazines like National Review, The Atlantic, The New Yorker, The American Conservative, and the old Weekly Standard when they are at their best exemplify great opinion journalism because they’re both honest about their biases and honest about when the side they’re rooting for falls short. A liberal magazine is going to be more skeptical about Republicans and vice versa. And that’s not just fine, it’s objectively good, so long as the skepticism fuels making good arguments.

Parties—both formal and informal—have an institutional interest in distrusting the press releases and pronouncements of their opponents. They offer critical opposition to the groupthink and self-serving shading of facts that are inherent to all partisan endeavors. Obviously too much partisanship can be bad, but too little—or none—can be worse. Single-party countries—today’s China, the Soviet Union, etc.—are not full democracies because the interests of the party and the state become fused and the people have no vehicle to express their opposition or to hold the regime accountable.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.