“You can chase nature out with a pitchfork, but she will always keep running back.”

This idea, from the Roman poet Horace, was the central idea of my book, Suicide of the West (now out in paperback, as I’ll never let you forget).

Farmers understand this. A bunch of pastoral paintings and poems notwithstanding, farmers are closer to frontline troops in the war against nature. If you fail to tend to your crops, refrain from pulling weeds, tending to the needs of the soil, chasing off critters, etc., nature will take back what is hers. If a farmer abandons his land, it will not take long for nature to reclaim it. Wait long enough and, depending on the geography, future visitors will be surprised there was ever a farm there in the first place. There are parts of Maine where you can stumble onto the stone walls of old farms in the middle of the woods. Every few years, explorers in South America or Asia discover stone temples in the heart of the jungle, because the jungle always grows back.

Human nature is special because humans are special. But the “nature” part is not something to trifle with. Without painstaking effort, what makes humanity special will be reclaimed by human nature itself. When the children in Lord of the Flies are left to their own devices, they do not adopt Robert’s Rules of Order to deliberate what is best for the group. They revert back to their nature. They become tribal, superstitious, and cruel. In The Walking Dead, the protagonists spend the first few seasons grappling with the reality that, absent the rule of law and the institutions of just authority, the protocols of the more fundamental laws of survival kick in: Strength in numbers, distrust of strangers, Us vs. Them. The zombies are simply a pulp fiction exaggeration of the dangers of jungle living, the real threat are other humans who see survival as a zero-sum calculation. “You’re the butcher, or you’re the cattle.”

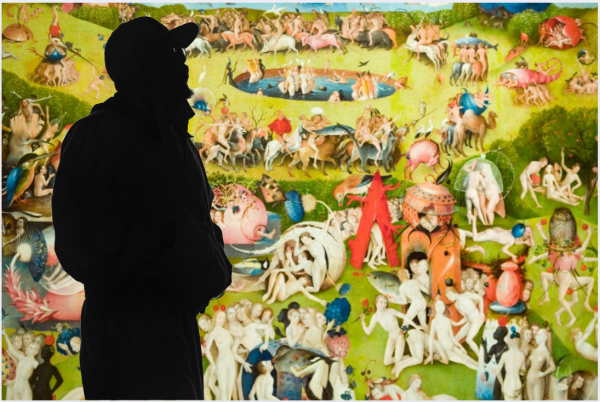

This is how I wish people could understand the American experiment. It is a garden hacked out of the jungle of human history. For 99.9 percent of our time on earth, humans were governed not by the rule of law, but by the rule of men. Monarchy is just a fancy term for the tyranny of the Big Man. It may have more ceremonial and theological ornamentation, but scrape off the pomp and you’re left with might makes right.

The great exceptions.

But civilization, like the Constitution, is not a suicide pact.

It is not an accident that when we face a crisis we fall back on our more primitive instincts for survival. This is not an indictment. When invaders are at the door, we want generals—not debaters. We suspend the rules—hopefully according to other rules that allow for their own temporary suspension—as we understand that a firefighter shouldn’t wait for a warrant to kick down your door if he sees smoke billowing out of your bedroom window. A paramedic need not ask permission to touch you—if you’re having a heart attack.

In other words, any remotely serious and decent society understands that the rules in a crisis are going to be different from the rules during normal times. Hopefully, such societies will have anticipated this possibility and will have created procedures—in the Constitution and in the law—that take this distinction into account. These procedures may not be adequate to every crisis, but there will be enough experience with other crises to work from. Where there are gaps it will fall to statesmen to explain why deviations are necessary, and God willing, temporary.

This is why I am so exasperated with the dumb glee of those who are using the pandemic to claim that libertarianism and/or traditional conservatism were always inadequate. Every morning I catch liberals on Morning Joe delivering morally preening stemwinders on how this pandemic proves the ethical splendor and metaphysical necessity of activist government. They talk as if champions of limited government have been arguing against firefighters, police, and hospitals, and that, therefore—ha ha—this proves how dumb the libertarians were all along. What is actually revealed by these smug perorations isn’t the inconsistency of the classical liberals, but the ignorance of their critics who don’t realize they’ve been fighting straw men all along.

The same principle that says we need generals when barbarians are at the gates says we need doctors when a deadly disease strikes. There is no hypocrisy here, unless some random chatroom Randian or campus anarcho-capitalist is suddenly the official spokesperson for all of conservatism.

I’ve repeated a line from Ramesh Ponnuru so often I sometimes think it’s my own. Libertarianism is the best political philosophy imaginable, save for two blind spots: The existence of children and the need for foreign policy.

In other words, a system whereby people are free to make their own choices, own the fruits of their labors to the greatest extent possible, and live how they want to live so long as they do not harm others is as close to an ideal as we can get. The problem is that such a system is not natural. Societies worth preserving have to take care that the next generation is raised to respect and value the system they are born into. This requires attending to the character formation of children. Likewise, in a world where most societies are not going to be equally enlightened, protecting the country from foreign threats is a necessity. This is why the heroes of The Walking Dead must have different rules for the strangers outside their walls than the citizens within them. Nature, red in tooth and claw, must be respected if it is to be held at bay. This applies to men with swords and to viruses alike.

Adrian’s wall.

For more than a century, progressives have looked for ways to blur these distinctions, to acquire for the state powers that are only legitimate in a free society when there is a crisis. It hasn’t just been progressives—power is seductive to humans regardless of ideology. But it has been progressives who have made it an ideological imperative to use various moral equivalents of war as excuses to fight poverty, inequality, alienation, climate change, etc., without fidelity to constitutional guardrails and limits.

That’s changing. Adrian Vermeule, a respected constitutional scholar, is the latest example of this change. He has written an essay for The Atlantic that has some hoping—in vain, alas—that it is Swiftian satire. He believes that “originalism”—in the most basic terms, the view that the Constitution must mean what it says—has outlived its utility. It must be replaced with a jurisprudence that puts the “common good” above all, even the plain meaning of the Constitution. It demands, he insists, a “candid willingness to ‘legislate morality.’”

“Libertarian conceptions of property rights and economic rights will also have to go,” he writes, “insofar as they bar the state from enforcing duties of community and solidarity in the use and distribution of resources.” But the “main aim” of his “illiberal legalism” (his term!) is “to ensure that the ruler has the power needed to rule well.”

Vermeule’s admirable honesty about what he wants does not detract from the grotesqueness of his desire.

I will leave it to others to debate his take on originalism, save to make a single legal point. While I have no doubt that some champions of originalism embraced this philosophy for less-than-pure motives, it seems inevitable that “haves” will disproportionately embrace a jurisprudence that supports their right to have what they have against the claims of the more numerous “have-nots.” But originalism is not simply that, no matter how much the old progressives and new reactionaries insist otherwise. The basic idea of originalism is that our break with the more natural order of the strongman needs to be dogmatically protected from those who would exploit the fierce urgency of now to smash the constitutional walls around the garden of liberty.

Again, to Vermeule’s credit, he at least admits it. He wants to return to a more medieval understanding of not just “leadership,” but outright “rulership.” The progressives have always adorned their reactionary conception of power with the language of modernity and progress. They start with the assumption that liberal democratic capitalism is backward and must be transcended to some more “evolved” form of social organization. They have had to pay lip service to concepts of freedom by arguing for the economic “liberation” that comes with positive rights to housing, health care, work, etc.

Vermeule’s conception is far more proudly feudal. He talks endlessly about the need for “hierarchies,” the way feudal lords talked about their obligations to their serfs. This is closer to the jurisprudence of Justus Moser than Oliver Wendell Holmes.

On a practical level, his argument’s most fatal flaw stems from the fact that there is nothing in his argument for unbridled rule by just rulers that prevents the unbridled rule of unjust rulers. But once you argue away those safeguards for your team, you are left with no arguments against the other team when they get in power. And to put it bluntly, Vermeule’s team is wildly outnumbered. This problem was recognized by the Founders early on, which is why they argued against kings of any label, because there was no way to create a system that granted adequate power to rulers that ruled well—but not to all other kinds of rulers.

I very much doubt that Vermeule will have anything like the impact he and his acolytes hope for. But he is opening a second front in the conservative effort to hold nature at bay and pass on a garden of liberty. He is trying to lay siege at the conceptual rear wall and lending aid and comfort to those who believe that no one has the right to pursue their own definition of happiness.

Photograph by Education Images/Universal Images Group/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.