The Mob Ascendant

The spirit of the mob is taking over our politics.

Dear Reader (including the entire cast of Cats),

In difficult times like this, when passions run high and trust is in short supply, I like to think about happier things. Specifically, in my quiet moments, when seeking a respite from the shouting and a replenishment of serenity, I will meditate on the fact that the only thing stopping Jeffrey Epstein’s former party pals from going down with him is the honor and integrity of Jeffrey Epstein.

That’s a nice thought.

I mean, there’s so much we don’t know about Epstein as of now. But whether the ephebophilic Gatsby is in fact a straight-up forcible rapist and Ponzi-scheme fraudster and sexual blackmailer—or if he’s merely an ephebophilic statutory rapist and party animal with questionable finances, I think it’s a pretty safe bet that he’s not the type to honor confidentiality and take one for the team. Sure, he may have said, “What happens at 30,000 feet stays at 30,000 feet,” but if you were Bill Clinton or some other member of Epstein’s Mile High Club and you did something wrong, would you sleep soundly counting on Jeff to stay true to his word?

“They’ll never break Epstein. He’s a stand-up guy!”

This Ugsome Moment

Anyway, I thought I would start with something positive.

One of the things that makes politics so depressing right now is that the incentive structure is set up to reward the worst behavior of the worst actors. The “Squad”—or, as I like to call it, The Committee to Reelect the President—has every incentive to behave in exactly the way Donald Trump wants them to. And Donald Trump has every incentive—or believes he does—to behave in precisely the way the Creepers want him to. They benefit when Trump makes them the face of the Democratic Party, and he benefits, too. And so do many of the people invested in Trump, including the media, which feeds parasitically on the Trump panic it helps fuel by helping Trump fuel it. The entire incentive structure is set up so that easiest path is the one where everybody lives down to our lowest expectations.

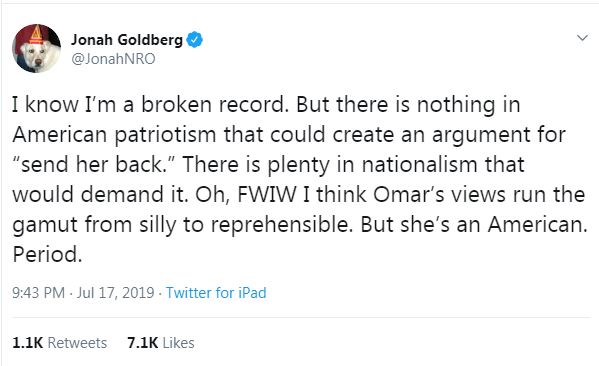

The other night I tweeted:

As you might expect, lots of people had their complaints about this tweet. I’m not going to bother with most of them. I never said that Trump was “demanding” she leave. I said there is something internal to the logic of nationalism that demands the sort of thinking that leads to people chanting “send her back!”

American patriotism, in my Buckleyesque understanding, is creedal, while nationalism is romantic—i.e. emotional, passionate, and pre-rational. Those emotions are not necessarily sinister, but neither are they a coherent philosophical worldview. Passion can make us do crazy or terrible things. That doesn’t mean passion is bad; it just means it needs to be channeled and directed productively. “Why has government been instituted at all?” asked Alexander Hamilton. “Because the passions of men will not conform to the dictates of reason and justice without constraint.”

This points to why I’ve always been skeptical of populism: Because it puts the passion of the crowd at the forefront. Allow myself to repeat…myself. Elias Canetti notes in his book Crowds and Power that, inside the crowd, “distinctions are thrown off and all become equal. It is for the sake of this blessed moment, when no one is greater or better than another, that people become a crowd.”

“But,” Canetti adds, “the crowd, as such, disintegrates. It has a presentiment of this and fears it…Only the growth of the crowd prevents those who belong to it from creeping back under their private burdens.”

There’s an enforced conformity, a tribal groupthink, to crowds. They crowd out individuality and distinction. “When men exercise their reason coolly and freely on a variety of distinct questions, they inevitably fall into different opinions on some of them,” James Madison observed. “When they are governed by a common passion, their opinions, if they are so to be called, will be the same.”

This was the observation underlying Randolph Bourne’s distinction between the government and the state. The government is where people argue and negotiate competing interests. The state— which for Bourne emerged with the white-hot passion of war—is a mystical representation of “us,” where disagreement becomes a kind of treason.

That rally wasn’t about patriotism, but nationalism. Donald Trump hasn’t the foggiest clue about America’s creeds. But he does have an instinctual appreciation of the emotional triggers of nationalism. No major party nominee in American history ran down the United States of America as much as candidate Trump did in 2016. His description of America was borderline dystopian, blurring the moral distinctions between America and Putin’s Russia. He said America was run by stupid and weak people and was a “laughingstock” on the global stage. Not even the most race-obsessed left-winger would have said of America that “…our African-American communities are absolutely in the worst shape they’ve ever been in before. Ever, ever ever.”

Nobody said: “Why don’t you leave if it’s so bad here?”

Now that Trump sees himself as the romantic incarnation of the nation—l’etat est moi—the new hotness is “America, love it or leave it.”

Trump may have retroactively said that he didn’t like the “send her back” chant, though there’s no evidence he felt that way at the time. But you can be sure he’ll return, like a dog to his vomit, to his favorite rhetorical trick of saying, “I’m not supposed to say it, but …” or “Donald Trump would never say…but…” He loves apophasis, the technical term for saying you’re not going to say something as a way to say what you wanted to say. “I won’t say that Jeffrey Epstein collected Sears’ Junior Miss catalogs. I would never talk about that huge stack by his night table.”

And even when he doesn’t resort to that shctick, he lets the crowd do it. When he got grief for calling Ted Cruz a “pussy,” he told a woman in a New Hampshire crowd:

You said a terrible thing. You know what she said? Shout it out, because I don’t want to say…Okay, you’re not allowed to say, and I never expect to hear that from you again. She said he’s a ‘pussy.’

So long as the crowd wants to hear “send her back!” Trump will find a way to give the people—his people—what they want. As Willie Stark says to the crowd in All The King’s Men: “Your will is my strength. Your need is my justice.”

It’s Binary If You Want It To Be

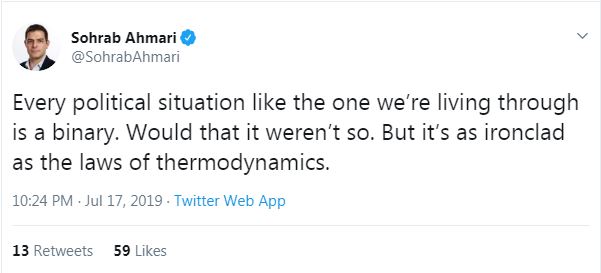

Sohrab Ahmari tweeted amidst the Trump rally the other night:

I think this is axiomatically true—if enough people believe it to be true. Then, it becomes true. It’s just not obvious to me that Sohrab doesn’t want it to be true. In another tweet he asserted—and later defended—the claim that Ilhan Omar “sets the Democratic agenda and enjoys deep and broad media support.”

To be generous, evidence that she sets the Democratic agenda is sparse. That she enjoys deep and broad media support strikes me as largely true, though her anti-Semitic comments and the effort to censure her were not marked by glowingly positive or scant coverage. What gets her positive press coverage is Trump’s attention. He’s making her more popular with the progressive base, and she’s helping Trump remain popular with his base. This is what I mean by the incentive structure being such a hot mess. Team Trump want it to be true not just because they think that’s the only way Trump can win, but also because it gives them a permission structure to be in a permanent state of (culture) war that justifies the crowd mentality that demands uniformity and “Flight 93ism” forever.

The Idiotic Ingratitude of the Left

But back to my tweet. A lot of progressives complained that I called out Omar as well. Just as so many on the right want a clean narrative about Omar & co., many on the left cannot stomach any muddying of the waters about Trump. Omar must be a pure victim, singled out for her skin color, gender, and religion. Screw that. She’s awful. Or to be fair, her views are awful. The “send her back” chant was awful, but the idea that it’s racist to criticize her is absurd.

For two years, we’ve constantly heard that Trump has violated constitutional norms. Fair enough, I say (though it’s often hard to stomach such talk from those who want to pack the courts and police free speech). But where is the love for the Constitution? I mean, why is it terrible to violate constitutional norms if you also believe that the Founding Fathers were nothing but evil slaveholders and that America remains an irredeemable swamp of white supremacy? Questioning people’s patriotism is ugly, but so is giving so many people good reason to question it. The broad impression we get from the left is that Trump is evil not because he’s violating the ideals of America but because he represents them. It’s a constant drumbeat about America’s invincible racism, sexism, and xenophobia. It’s a bit off-topic but perfectly representative of the times (and Times): This week, the New York Times ran a piece for the Apollo anniversary to remind everybody that the Soviet Union was better at making space more diverse.

Poor Joe Biden is trying to run as a liberal who thinks America is a pretty good place, but the Democratic base is responding to that like the guys at Delta House when Flounder’s picture appears on the screen. Would it kill some of these people to say something nice about the country? I get dizzy trying to diagram the logic of saying Trump is un-American but that being an American is a bad thing.

Meanwhile, the political press knows that the Woke Gang of Four are wildly to the left of their party (and the party is to the left of the Democratic electorate). AOC types didn’t win the House; moderates did. Nancy Pelosi isn’t a racist for dismissing AOC & co.; she’s a pragmatist. And yet they’re acting as if this binary stuff were true, too. David Broder once said that the job of a political journalist is to be a “fight promoter.” I’m not sure I fully buy that, but to the extent it is, they’re wrestling promoters, and they’ve bought into the kayfabe. It’s like everyone wants to put the “ug” in ugsome.

Various & Sundry

Canine Update: The doggers are handling the heat better than the humans. I’ve been getting up even earlier for the morning perambulations in vain hope of evading the wrath of Damnable Helios. I can’t even blame Pippa for rushing to creek. It makes her so happy. The big challenge in my neighborhood is that while the human calendar says it’s summertime, the rabbit calendar thinks this is second spring, and there is a host of baby bunnies all over the place. Zoë hasn’t caught any, and we’re doing everything we can to avoid bunny infanticide. But it does make everything more stressful. Another problem: The issue of scritch inequality is becoming more acute. I think I leave the TV on when Bernie Sanders is talking too much.

ICYMI…

Why is Trump so down on Paul Ryan?

This week’s first Remnant, with A.B. Stoddard

Social-media shock stories amount to lazy journalism

This week’s second Remnant, with David Pietrusza (part one)

This week’s third Remnant, with David Pietrusza (part two)

And now, the weird stuff.

Animals who fear the human voice

Dog sets off motion detector camera

Can parents’ emotional trauma affect their kids’ biology?

Computers: the newest basketball coaches

World Taxidermy and Fish Carving Competition

Chimps bond over watching movies

Kids fake cry more than you think

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.