Hi,

Quinnipiac released a much-discussed poll that has some troubling findings. Apparently, a lot of Americans, particularly younger ones, said that if America were invaded by Russia the way Ukraine is now, they wouldn’t stay and fight. From the summary:

As the world witnesses what is happening to Ukraine, Americans were asked what they would do if they were in the same position as Ukrainians are now: stay and fight or leave the country? A majority (55 percent) say they would stay and fight, while 38 percent say they would leave the country. Republicans say 68—25 percent and independents say 57—36 percent they would stay and fight, while Democrats say 52—40 percent they would leave the country.

Among 18-34 year olds, more people say they would leave (48 percent) than stay (45 percent). Now, I’m with Charlie Cooke and others who are fairly disgusted by this, and I agree with Charlie’s argument for why we should be disgusted by it.

But I don’t believe any of it. If America were invaded, I’m sure that many of the people who say they’d “stay and fight” would be packing their bags for a refugee center in Mexico or Canada. And I’m sure many of the people who say they’d bug out would be sticking around to make Ivan pay. Yes, I’m saying that some tough-talking dudes with “these colors don’t run” bumper stickers would be high-tailing it out of here, and some snowflake soy boys would be ambushing Russian convoys in northern Michigan.

I don’t say this because of any hidden admiration for the soy boys or animosity for the good ol’ ones. I’m just saying that humans respond to reality differently than they respond to hypotheticals. As renowned social-psychologist Mike Tyson famously said, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.”

Obviously, this is a very hard thing to prove, but history is full of stories of improbable heroes and unlikely cowards. (There are other reasons to think these findings are unreliable. I can see why some young people would say they’d flee for reasons other than unpatriotic sentiment. If you have a bunch of small kids, you might think your first duty is to them. I don’t look at the male refugees in Poland and immediately think, “Look at all those unpatriotic cowards.” Everyone has a story.)

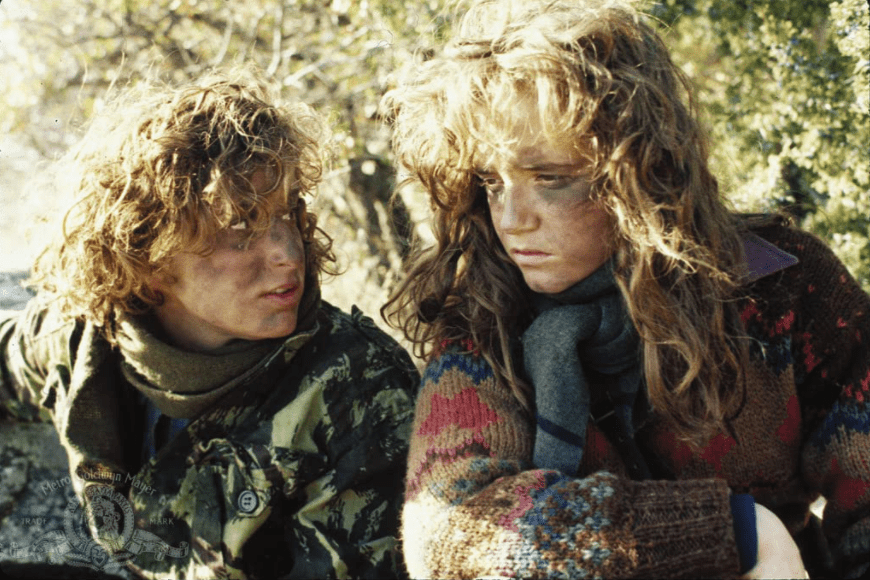

Consider that towering pillar of American cinema: Red Dawn. In the movie, you wouldn’t expect C. Thomas Howell to become a one-man Ruskie killing machine. Nor would you necessarily think Jennifer Grey or Lea Thompson would become hard-bitten warriors. People can surprise you. (And since we’re on the topic of Red Dawn, here’s a sidebar on it. The original first 1,000 words were all Red Dawn, and I figured I was losing the plot.)

One small data point in favor of my point can be found in the same poll. Quinnipiac finds that 8 in 10 Americans favor using force if Russia attacks a member of NATO. In 2019, YouGov asked people in a bunch of countries if we should use force if a NATO ally were attacked. Fifty-seven percent of Americans said yes. Now 80 percent do. What changed? It’s no longer a hypothetical question. In Germany, NATO—and defense spending, etc.—have not polled well. That same year, a majority of Germans opposed increased defense spending to meet NATO’s minimum requirements. Now, most Germans favor surging past the minimum. Heck, 73 percent of the historically ultra-pacifist German Greens favor massive defense spending increases. Meanwhile, the German far right is the least excited about rearmament, because history is funny. Indeed, across Europe, the pro-Putin far right is struggling for relevance, even as it races to catch up with public opinion.

It’s almost like people change their minds in response to new events.

As a generalization, with many caveats, I do think it is reprehensible that any Americans would say they wouldn’t defend their country when asked about a hypothetical invasion. I don’t think everyone who said they’d high-tail it believes in their own mind that they are unpatriotic or cowardly, but objectively speaking it’s hard to read the finding any other way. So while I don’t consider these results to be predictive of what many people would do, I find them depressingly reflective of what a lot of people think they’re supposed to say.

Think of it this way. If I asked you, “If you’re house was broken into by a murderer-rapist, would you stay and defend your family or would you get out as quickly as possible?” the correct answer—even if you have all sorts of rationalizations about getting help, etc.—is, “Of course I would stay.” Again, some of the people who say they’d stay and fight would run if it actually happened, and some of the people who said they’d run might actually stay. But the fact remains that if you say you’d leave your family to fend for itself, you have a warped sense of morality.

Or, if that doesn’t work for you, think about it this way. It’s a sign of massive social progress that majorities of Americans refuse to say they are racist. I think most say that because they’re not racist. But some racists surely lie to pollsters because they understand that you’re not supposed to admit such things. For instance, in 1958, 44 percent of white Americans said they’d move away if a black family moved in next door. Forty years later, that number had dropped to 1 percent. When the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964, only 18 percent of white Americans said they had a black friend. By 1998, that number was 86 percent. Again, some of those people were probably lying—to the pollster or themselves—but there’s no way to read such numbers and not celebrate the progress we’ve made. That nearly half of young Americans think it’s fine to say they wouldn’t defend their country is objectively bad, whether the numbers reflect a deeper reality or not.

Have some confidence.

Let me circle back to this point about how events can change our minds. One of the things I’ve drawn from the last few years is that many people hold their convictions lightly. Also, lots of people confuse opinions for convictions. Joe Biden thought pulling out of Afghanistan was what Americans wanted deeply as a matter of conviction (a view shared by Trump and many of his supporters). It turns out that for most Americans, this wasn’t a deep conviction but a lightly held opinion. If you asked Americans whether they’d be willing to leave Afghanistan the way Biden did—leaving Afghanistan to the Taliban and abandoning countless allies on the ground—Americans would have said no by huge margins. Similarly, whatever the polls said before 9/11, they were utterly useless in understanding what Americans would do after 9/11.

In the lead up to Putin’s invasion, I predicted that a lot of the pro-Putin sentiment on the right would disappear because, while it’s easy to entertain hypothetical and highly theoretical defenses of Putin, it’s another thing to defend bombing homes and schools on TV and social media every day. There’s still too much Putinophilia and apologia in existence. But it’s mostly confined to people who have little to no accountability to voters, and who are desperate to hold onto their niche followings on Twitter and TV or their boutique theories about why the West “really” dislikes Putin (he’s good on transgender pronouns!). Even Donald Trump had to switch from saying the invasion was “wonderful” to saying it was an “atrocity” in just a few days.

While I think Trump’s change of tune was entirely cynical and self-serving, I’m glad for it. I’m glad whenever politicians switch from a bad position to a good one when politics requires it. It may not speak well of the politicians, but it does speak well of Americans. In June 2014, war-weary Americans were evenly divided about whether we should do much of anything about ISIS. Then ISIS beheaded some Americans, and murdered, enslaved, and raped thousands, and Americans were like, “Nope.” Support for fighting ISIS reached 82 percent. Americans are almost always non-interventionist until we’re not.

So many of the arguments that take up our time—and especially my time—are little more than flashes of St. Elmo’s fire lighting up the airwaves with little relation to the reality on the ground. This is a good and decent country, and because of its prosperity Americans enjoy the luxury of using opinions like kindergarten toys. We smack each other with Lincoln Logs and shoot pieces of Lego at each other on a daily basis. But when events require us to put away childish things, most do. Because beneath our opinions rest some core commitments that run through the American character like veins of granite. We like freedom. We like fairness. And we actually like peace quite a bit, too. It’s just that when bullies and tyrants threaten any of these things, we get pissed. And we tend to do something about it.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.