Happy Friday! Today is the 251st* anniversary of the Boston Massacre. Did you know John Adams defended the British soldiers involved in court?

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

Leaked Department of Health and Human Services documents obtained by Axios show a dramatic rise in child migrants crossing the United States’ southern border, from 47 per day in the first week of January to 321 per day last week. The documents say the shelter system is currently at 94 percent capacity.

-

U.S. Capitol Police have requested a 60-day extension of the National Guard troop deployment around the Capitol amid heightened security threats. The Pentagon is currently weighing whether to grant the extension, which D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser does not support.

-

United Nations Human Rights Commissioner Michelle Bachelet said yesterday that police and security forces in Burma have killed at least 54 protesters and detained 1,700 following last month’s military coup. “The actual death toll, however, could be much higher as these are the figures the Office has been able to verify,” she added.

-

Bachelet also announced the need for an investigation into Ethiopia’s Tigray region to respond to reports of “sexual and gender-based violence, extrajudicial killings, widespread destruction and looting of public and private property,” as well as “war crimes and crimes against humanity.”

-

Initial jobless claims increased by 9,000 week-over-week to 745,000 last week, the Labor Department reported on Thursday. About 18 million people were on some form of unemployment insurance during the week ending February 13, compared with 2.1 million people during the comparable week in 2020.

-

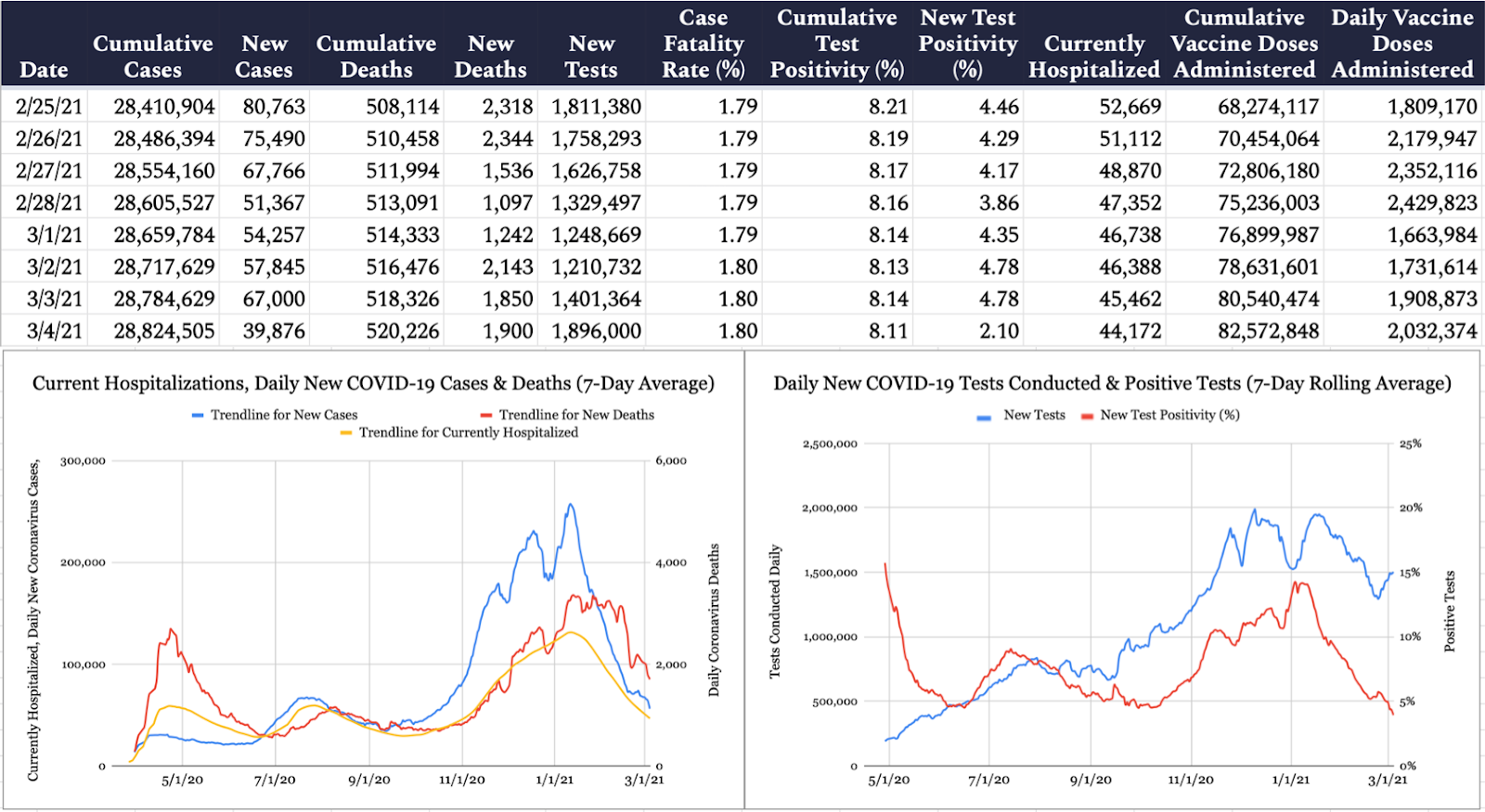

The United States confirmed 39,876 new cases of COVID-19 yesterday per the Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, with 2.1 percent of the 1,896,000 tests reported coming back positive. An additional 1,900 deaths were attributed to the virus on Thursday, bringing the pandemic’s American death toll to 520,226. According to the COVID Tracking Project, 44,172 Americans are currently hospitalized with COVID-19. According to the Centers for Disease Control, 2,032,374 COVID-19 vaccine doses were administered yesterday, bringing the nationwide total to 82,572,848.

H.R. 1 for the Money, 2 for the Show

After shipping President Biden’s $1.9 trillion stimulus package over to the Senate last Saturday, House Democrats turned back to some more longstanding priorities this week.

On Wednesday evening, the House voted almost entirely along party lines to pass the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, a police reform measure that was first introduced last summer. Shortly after, members voted 220-210 to once again pass H.R. 1, a wide-ranging package of voting, campaign, and ethics reforms that Democrats first voted on upon retaking control of the House in 2019.

Also known as the For the People Act, H.R. 1 will not become law during the current Congress as long as the filibuster remains intact. Good luck getting to 60 votes when even Sen. Mitt Romney is strongly opposed.

Still, it’s worth digging into the legislation, which could in time prove to be what ultimately does the filibuster in. “I have favored filibuster reform for a long time, and now especially for this critical election bill,” Sen. Amy Klobuchar told Mother Jones this week. “We have a raw exercise of political power going on where people are making it harder to vote and you just can’t let that happen in a democracy because of some old rules in the Senate.” (Two of Klobuchar’s colleagues—Sens. Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema—remain strongly opposed to ending the filibuster.)

If signed into law, H.R. 1 would massively overhaul how elections are run in this country—and the apocalyptic rhetoric on both sides of the aisle reflects that.

In remarks just before the bill’s passing, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi compared the moment to Valley Forge, saying Democrats “must win” the fight for H.R. 1 because “everything is at stake.” Former Vice President Mike Pence—in some of his first public comments since leaving office—argued that H.R. 1 would “give leftists a permanent, unfair, and unconstitutional advantage in our political system.”

So what’s actually in it? The bill is broken up into three different sections: Voting rights, campaign finance, and lawmaker ethics.

In the voting rights section, H.R. 1 would create a baseline set of federal requirements for how states across the country administer elections. It would mandate that states automatically register all eligible citizens to vote, and require same-day voter registration to be offered to all eligible voters. It would allow voters to meet any state’s voter identification requirements with a “sworn written statement” signed under penalty of perjury, establish Election Day as a national holiday, implement no-excuse absentee voting, and require 15 days of early voting at a minimum. The legislation would restrict the reasons states could remove a name from its voter rolls, and restore the franchise to all incarcerated individuals released from jail. It would also attempt to curb gerrymandering by requiring states to create independent redistricting commissions to redraw congressional districts as necessary.

The campaign finance section of the bill includes stricter rules to limit money in politics, along with additional regulations on foreign interference in U.S. elections. H.R. 1 would require more transparency from so-called “dark money” groups that spend money in elections. Super PACs, for example, would have to publicize their donor lists. It would also seek to encourage small-dollar donations to campaigns through two programs: The “My Voice Voucher” pilot program would give qualified individuals $25 to donate to a congressional candidate of their choice, and a six-to-one federal matching program (capped at $200) that is paid for through a 4.75 percent tax on civil or administrative fees. If, for example, someone donated $100 to a congressional campaign, the federal government would match that with $600 of public funds, for a $700 total donation.

On election security, H.R. 1 mandates that campaigns report any foreign contact they receive to the proper authorities within a week. The Federal Elections Committee would be required to alert a state to a concerted foreign disinformation campaign, and the bill even offers rules and regulations on using deepfakes in campaigns.

The final section of H.R. 1 is the ethics portion. Supreme Court justices are currently the only federal judges who are not bound by the ethics rules in the judicial Code of Conduct—H.R. 1 would change that. This section would also tighten restrictions on lobbyists, expand the definition of the term “lobbyist,” and limit executive-branch employees from overseeing matters that are likely to be of interest to a past or future employer.

In a section no-doubt drafted in response to former President Trump’s business dealings, H.R. 1 would require the president and vice president to divest from all investments that may pose a conflict of interest while in office. The act also would require presidential and vice presidential candidates of major political parties to disclose their tax returns of the most recent 10 years.

President Biden applauded House passage of the legislation in a statement Thursday morning. “The right to vote is sacred and fundamental—it is the right from which all of our other rights as Americans spring,” he said. “This landmark legislation is urgently needed to protect that right, to safeguard the integrity of our elections, and to repair and strengthen our democracy.”

Republicans felt differently. “If you liked how the last election was run, you’re going to love H.R. 1,” Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy said. “It’s got all of Election 2020’s greatest hits—nationalized, federally funded, and designed to keep Democrats permanently in power.”

“This scheme would mandate a federal takeover of elections, centralize election administration in Washington, DC, and make permanent universal ‘pandemic-style’ mail-in voting that undermines trust in our elections,” added Rep. John Joyce.

McCarthy and Joyce were two of the more than 120 Republican members of Congress that signed onto a lawsuit back in December seeking to toss out the electoral votes of Michigan, Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. And on January 6, they once again objected to Electoral College votes from certain states.

“I think that [Republicans’] conduct in the wake of the election disqualifies them from being experts or even responsible commentators on what democracy in America should look like,” H.R. 1’s lead sponsor Rep. John Sarbanes said this week.

But there’s plenty of opposition to H.R. 1 from Republicans who didn’t fully embrace the post-election lies, too. In addition to Romney’s aforementioned resistance, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell delivered remarks on the Senate floor last week.

“This sweeping federal takeover would be exactly the wrong response to the distressing lack of faith in our elections that we’ve recently seen from both political sides. After both 2016 and 2020, we saw significant numbers of Americans on the losing side express doubt in the validity of the result,” McConnell said. “We cannot keep trending toward a future where Americans’ confidence in elections is purely a function of which side won. A sweeping power grab by House Democrats, forcibly rewriting 50 states’ election laws, would shove us farther and faster down that path.”

Vote, Vote, Vote Your Boat

Thought we were done with coverage of voting laws and electoral reform? Think again!

Earlier this week, the Supreme Court heard arguments about the legality of two Arizona voting provisions—but the merits of those provisions are just part of what is at stake with this case.

One law prevents “out-of-precinct voting,” meaning that, even in elections that are the same across precincts, a person’s vote wouldn’t count if they show up at the wrong one. The other bans “ballot-harvesting,” which makes it illegal for a person to turn in someone else’s absentee ballot—unless they are a family member, caretaker, election official, or mail carrier.

Legal experts widely expect the Court to uphold the two Arizona laws. What they’re less sure of is what standard the court will use to decide the case under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits voting procedures and practices that discriminate on the basis of race, color, or being a member of a particular minority group. The case is being watched so closely because of this uncertainty.

“The larger issue is how exactly the Court will rule,” Ilya Shapiro, a constitutional scholar at the Cato Institute, told The Dispatch. “Will it set a standard making it hard to bring Section 2 claims? There’s not much jurisprudence on what you have to lay out for a valid Section 2 claim because for a long time Section 5 … that took care of most of this stuff.”

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, also known as the “preclearance requirement,” gave the federal government oversight over certain states that had a history of making racially discriminatory voting laws before those states could change their laws. In 2013, the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder ended the practice of preclearance and held that Section 2 litigation—like the case at issue here—would be sufficient to protect the rights of minority voters.

Although court watchers have highlighted this case as one of the most important of the term—with far-reaching implications for voting laws throughout the country—the oral arguments did little to clear up the issues at stake. As Justice Elena Kagan said after hearing more than an hour of arguments from three of the four advocates, “the longer this argument goes on, the less clear I am as to how the parties’ standards differ.”

In part, that’s because there is no easy answer. Take the ballot collection law. In 2005, former President Jimmy Carter and former Secretary of State James Baker released the recommendations of the Commission on Federal Election Reform. In their 91-page report, they recommended that “the practice in some states of allowing candidates or party workers to pick up and deliver absentee ballots should be eliminated.” Currently, more than a dozen states have laws as stringent or more so than Arizona’s when it comes to ballot collection.

On the other hand, the attorney for the Democratic Secretary of State argued that Arizona is unique: Native American voters in Arizona “rely on ballot collection to vote,” as “they don’t actually have home mail service or access to postal facilities.” Consequently, the impact of the anti-ballot harvesting law was felt disproportionately by that group of voters.

But how much of an impact is enough, and what data do we use to judge that impact? Non-white voters were twice as likely as white voters to vote out of their correct precinct and have their ballots discarded. But there were only about 4,000 out-of-precinct voters, meaning that less than half of 1 percent of minority voters who voted in Arizona were affected by the law.

Does it matter that one of the legislators who introduced the anti-ballot harvesting bill in 2011 “was in part motivated by a desire to eliminate what had become an effective Democratic GOTV strategy,” according to the lower court? (The legislator had barely won his previous election, attracting over 80 percent of white voters but only 20 percent of Hispanic voters.) Does it matter that it wasn’t until five years later that a bill that contained this provision actually passed? Does it matter if we don’t know the motivations of the other 89 Arizona legislators from that term? Does it matter that no actual evidence of fraud was ever cited by any legislator?

At least five of the Supreme Court’s nine justices will need to agree on what standard the lower courts should apply when a state makes its voting laws more restrictive.

A decision is expected in June.

Worth Your Time

-

Is President Biden living up to his lofty ambitions of unity in this moment of extreme polarization? Peter Nicholas tackles this question in his latest for The Atlantic. The president, Nicholas argues, has at the very least paid lip service to ideas of bipartisan comity by fostering personal relationships with Republican lawmakers and inviting members of both parties to the White House for meetings on various priorities. But neither he nor Republicans have thus far budged an inch on the first major policy fight of his administration. “The question is whether these attempts at bipartisanship are cosmetic, or whether they reflect Biden’s natural instincts, represent a calculated strategy, or are some combination of all three,” Nicholas writes.

-

Republican pollster Kristen Soltis Anderson makes an important point in her latest column: The descriptors “Republicans,” “conservatives,” and “Trump supporters” should not be used interchangeably, as—while there is certainly plenty of overlap—they describe three distinct constituencies. A recent survey from Anderson’s firm, Echelon Insights, found 43 percent of respondents “belong to the political Right, either because they consider themselves Republicans, conservatives, or are very favorable to Trump himself,” she writes. “But only 13 [percent] are part of all three of those groups, highlighting interesting differences in the way voters on the Right think of themselves personally.”

-

In his latest piece for Business Insider, Josh Barro argues that Scott Gottlieb—former Trump administration FDA commissioner and Pfizer board member—has consistently provided the best public health guidance throughout the pandemic. “It’s okay for public health guidance to change when circumstances change, but the 15-day promise was never credible and should not have been issued. The public is understandably weary of a year of rules, and wary of a public health establishment that — after those first overconfident messages — often seems loath to admit things are about to get much better,” Barro writes. “To be credible, people who hope to influence public behavior need to meet the public where it is — giving realistic guidance and concrete timelines about when and how they can change their behavior soon, if not right now.”

Something Fun

Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin used a procedural mechanism on Thursday to force the Senate clerks to read the entirety of the Democrats’ $1.9 trillion (and 628-page) stimulus package aloud. Here’s a flashback to how Congress handled a similar situation a little over a decade ago.

Presented Without Comment

Also Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

Is the Equality Act necessary to codify Bostock v. Clayton County? How might the Equality Act affect religious liberty, if at all? How do we definitively differentiate between men and women? On Thursday’s episode of Advisory Opinions, David and Sarah chat about invidious sex discrimination as it relates to the Equality Act, and what this law means for the future of nondiscrimination law if it is passed by the Senate. Stick around for a conversation about Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, a Supreme Court case that deals with the Voting Rights Act.

-

In his latest Vital Interests (🔒), Thomas Joscelyn examines the utility—or lack thereof—of the ODNI’s February 25 report on the killing of Saudi dissident and Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi. The assessment, in addition to identifying culpable individuals already sanctioned under the Trump administration, loosely assigns blame to Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman—but it doesn’t provide evidence of this latter assertion. “It is highly likely that MBS did in fact order, if not directly oversee, the murder of Khashoggi,” Joscelyn writes, offering to bet his house on the matter. “Still, the ODNI assessment doesn’t add much, if anything, new in this regard. We already knew the facts contained within it. You can piece together as much from public reporting.”

-

David’s Thursday French Press (🔒) focuses on how current cultural and policy debates could mess with party alignments. “To support the traditional family, endorse immigration,” he argues. “To defend life, support child allowances.” He concludes: “Is there a vision for a GOP that welcomes immigrants, embraces parents, celebrates birth, and defends the entire Bill of Rights—by protecting free speech and religious liberty and by protecting vulnerable citizens from unlawful police violence and law enforcement overreach? I honestly don’t know. But I do know that’s the party I’d prefer.”

Let Us Know

If you were Sen. Joe Manchin or Sen. Kyrsten Sinema and could essentially dictate what H.R. 1 ultimately looks like using your leverage on the filibuster, what provisions would you keep and what would you cut? “All of them” and “none of them” are both acceptable—albeit boring—answers.

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Haley Byrd Wilt (@byrdinator), Audrey Fahlberg (@FahlOutBerg), Charlotte Lawson (@charlotteUVA), Ryan Brown (@RyanP_Brown), Sarah Isgur (@whignewtons), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Correction, March 5, 2021: Today is the 251st anniversary of the Boston Massacre, not the 250th.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.