Happy Friday! Out with general manager Ryan (Pace) and head coach Matt (Nagy), in with general manager Ryan (Poles) and head coach Matt (Eberflus). Look out NFL, the Bears are #Back.

[Editor’s note: Chicago is just jealous of general manager (B)rian (Gutekunst) and head coach Matt (LaFleur).]

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

The Bureau of Economic Analysis reported Thursday that real gross domestic product (GDP) increased at an annual rate of 6.9 percent in the fourth quarter of 2021, and 5.7 percent in 2021 as a whole. The former blew past most analysts’ expectations, and the latter represented the United States’ fastest year-over-year growth since 1984.

-

Justice Stephen Breyer on Thursday formally announced his intention to step down from the Supreme Court at the end of the court’s current term later this year—on the condition that “by then [his] successor has been nominated and confirmed.” President Joe Biden told reporters he has not yet selected Breyer’s successor, but confirmed he will nominate a black woman for the position—likely by the end of February. Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin, a key swing vote on any confirmation, told MetroNews in West Virginia it would “not bother” him if the nominee was more liberal than he is, as long as she is qualified.

-

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said Thursday that the United States’ written response to Moscow’s security demands did not include a “positive response” to their concerns about potential NATO expansion to the east. Russian President Vladimir Putin will now review the United States’ response, Lavrov said, and “decide on our further steps.”

-

Press Secretary Jen Psaki announced Thursday that German Chancellor Olaf Scholz will visit the White House on February 7 to meet with President Biden and discuss “ongoing diplomacy and joint efforts to deter further Russian aggression against Ukraine.” Biden spoke to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on the phone yesterday to reaffirm “the readiness of the United States along with its allies and partners to respond decisively if Russia further invades Ukraine.”

-

The Omicron wave continues to abate, with the average number of daily new COVID-19 cases in the United States falling 29 percent over the past two weeks. But average daily COVID-19 deaths, a lagging indicator, are up 18 percent over the same span.

-

The Labor Department reported Thursday that initial jobless claims decreased by 30,000 week-over-week to 260,000 last week.

State of the Economy

There’s really no better word to describe the U.S. economy right now than “weird.” The unemployment rate is at 3.9 percent, lower than its been at any point since 1970 save April 2000 and mid-2018 through March 2020. Year-over-year wage growth is near its highest level since the metric began being tracked in the mid-2000s. Yesterday, we learned that real GDP grew at a 5.7 percent clip in 2021, its fastest rate since 1984. After a global pandemic led most countries around the world to more or less shut down commerce for several months, the U.S. economy is all of … 1 percent smaller than it likely otherwise would have been.

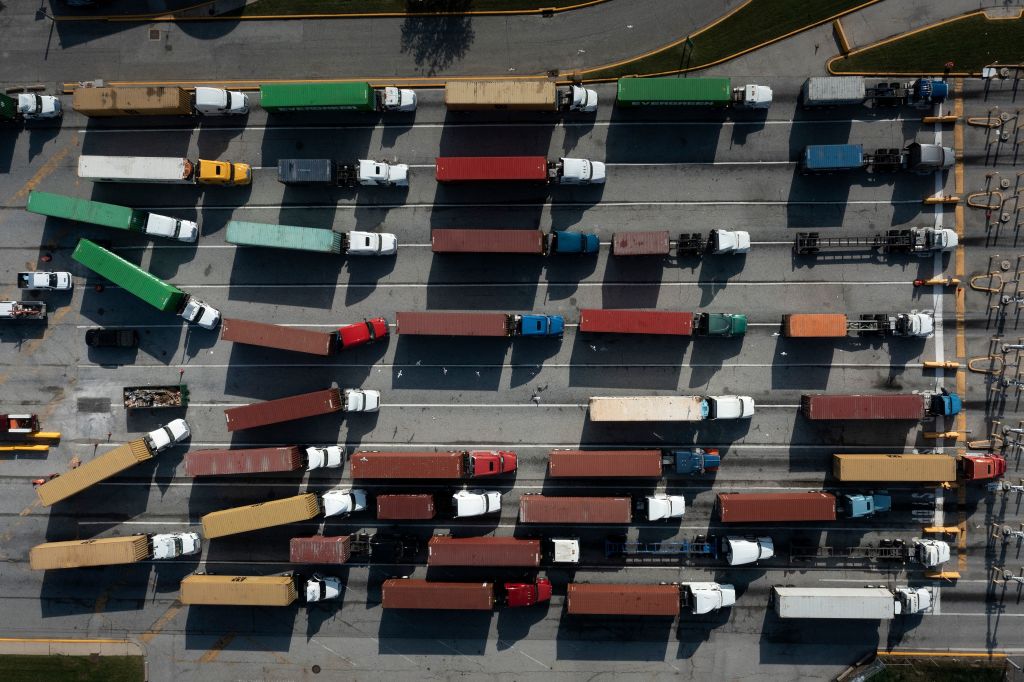

Yet 72 percent of respondents in a Pew Research Center poll published earlier this week believe the U.S. economy is in only “fair” or “poor” condition. Why do they think so? Because gas costs 50 percent more now than it did a year ago, and beef prices at the grocery store are nearly 20 percent higher. They have to shell out nearly 40 percent more to buy a used car if they can manage to find one, and—although the supply chain crisis is not as dire as viral pictures of empty store shelves can make it seem—there are plenty of products that are harder to come by.

People interact with “the economy” as both workers and consumers, and for many, the benefits of a tighter labor market—one or two raises over the course of the year—are not outpacing the reality of going shopping or paying bills in 2022. Real disposable personal income—which accounts for the effects of inflation—decreased 5.8 percent in the fourth quarter of 2021.

Still, President Biden couldn’t let those record GDP numbers come and go without spiking the football. “For the first time in 20 years, our economy grew faster than China’s,” he said Thursday. “This is no accident. My economic strategy is creating good jobs for Americans, rebuilding our manufacturing, and strengthening our supply chains here at home to help make our companies more competitive.”

The Q4 GDP numbers were padded a bit by retailers restocking depleted shelves—“inventory investment” accounted for more than half of the Q4 increase and isn’t likely to carry into 2022 at the same rate—but all in all, 2021’s 5.7 percent real GDP growth represented a remarkable rebound from the depths of the pandemic. In July 2020, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that number would be 4 percent. In February 2021, after accounting for the development of the vaccines, the CBO forecast a 4.6 percent increase.

(It also estimated 1.9 percent consumer price index inflation, so maybe we should start taking those analyses with a few more grains of salt.)

There are many protagonists who deserve credit for 2021’s unexpected economic growth, but you can’t tell the story without prominently featuring the Federal Reserve and its highly accommodative monetary policy. Unfortunately, those near-zero interest rates and tens of billions of dollars in monthly asset purchases are main characters in the inflation story, too.

But on Wednesday, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell and the rest of the Federal Open Markets Committee forged ahead with their hawkish pivot outlined at their December FOMC meeting—and if anything, the sense of urgency was even greater this time around.

“In light of the remarkable progress we have seen in the labor market and inflation that is well above our 2 percent longer-run goal, the economy no longer needs sustained high levels of monetary policy support,” Powell said. “That is why we are phasing out our asset purchases and why we expect it will soon be appropriate to raise the target range for the federal funds rate.”

Since that December meeting, the general consensus among Fed watchers was that the central bank would wrap up its taper in early March and begin hiking interest rates at its next meeting on March 16. With inflation indicators continuing to worsen in recent weeks, some investors and analysts began to wonder if that timeline would be moved up even further, possibly to this week’s meeting. It wasn’t.

“They certainly weren’t more dovish than the baseline expectation,” said John Fagan, who directed the Treasury Department’s Markets Room from 2014 to 2018. “They were, if anything, slightly more hawkish, but only by degrees. … Going in, [futures markets expected] basically four rate hikes for the full year. Now it’s more like 4.5, rounding up to five.”

Reporters gave Powell every opportunity to take a more dovish tack and quell the markets in his post-meeting press conference, but he repeatedly refused to do so. Would the Fed rule out raising interest rates at consecutive meetings? “We’re going to be guided by the data.” Were they really thinking about shrinking the Fed’s balance sheet—which has more than doubled to nearly $9 trillion since March 2020—concurrently with rate hikes? “The balance sheet is substantially larger than it needs to be.” Are you worried about over-tightening monetary policy? “There’s a risk that the high inflation we’re seeing will be prolonged, and there’s a risk that it will move even higher.”

After spending most of 2021 dismissing inflationary concerns as “transitory” or “temporary,” the speed of Powell’s evolution in recent months has come as a surprise to plenty of analysts. “As the Fed began its conversion” back in November, Fagan said, “it has [certainly] operated with the zeal of the converted.”

There are trillions of dollars riding on Powell and his fellow board members’ ability to pull off a high-wire balancing act: cooling the economy enough to drop personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation from 5.7 percent back down to 2 percent without going too far and triggering a recession.

“What we need here is another long expansion,” Powell said, referring to the decade leading up to the pandemic that saw increases in wages and labor-force participation rate. “We’d love to find a way to get back to that. That’s going to require price stability, and that’s going to require the Fed to tighten interest-rate policy and do our part in getting inflation back down to our 2 percent goal.”

How? They know they’re going to cease the monthly asset purchases in early March and hike interest rates a few weeks later. But beyond that, they’ll take it day by day. “It is not possible to predict with much confidence exactly what path for our policy rate is going to prove appropriate,” Powell said. “And so, at this time, we haven’t made any decisions about the path of policy. And I stress again that we’ll be humble and nimble.”

Should They Stay or Should They Go?

Although the Kremlin continues to maintain Russia has no plans to invade Ukraine, pretty much everyone else—multiple countries’ intelligence agencies, national security experts, the White House, the Ukrainian government itself—is more or less convinced that the situation has the potential to get very bad very quickly. On Thursday, President Joe Biden told his Ukrainian counterpart, Volodymyr Zelensky, the United States believes there is a “distinct possibility that the Russians could invade Ukraine in February.”

With that reality in mind, the State Department this week began ordering diplomats’ families to depart from the U.S. Embassy in Ukraine and urging all American citizens in the country to “consider” doing the same. In a piece for the site today, Charlotte explores whether these steps are unnecessarily cautious, or long overdue.

In a press briefing this week, Secretary of State Antony Blinken addressed the Department’s response to the unfolding crisis in Eastern Europe.

“I authorized the voluntary departure of a limited number of U.S. employees and ordered the departure of many family members of embassy personnel from Ukraine,” Blinken said. “And given the continued massive build-up of Russian forces on Ukraine’s borders, which has many indications of preparations for an invasion, these steps were the prudent ones to take.”

But, he added: “I want to be clear that our embassy in Kyiv will remain open, and we continue to maintain a robust presence to provide diplomatic, economic, and security support to Ukraine.”

About 120,000 Russian troops are now stationed in the border regions, but some analysts caution that the deployments could be a ruse to extract maximum concessions from the U.S. and other NATO allies.

“[Putin] is doing everything to create the impression that Russia will invade within the next few weeks, so he’s moved the troops, moved the support, moved the logistics, removed his diplomats. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that he’s going to,” Peter Dickinson, editor of the Atlantic Council’s UkraineAlert, told The Dispatch. “There’s no way of knowing in advance whether he is genuine or whether it is an intimidation tactic.”

Moscow’s campaign to stir up hysteria inside Ukraine has already begun. In addition to cyberattacks of likely Russian origin targeting Ukrainian government websites, unknown actors have been circulating false bomb threats in schools across the country at record rates. Last year, there were more than 1,100 false alarms. In the first month of 2022 alone, there have been more than 300.

“There are efforts to create panic in the society. There is a new spate of false alarms,” Maryana Drach, director of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Ukrainian service, told The Dispatch. “We spoke to different schoolteachers, parents, and many are distressed.”

Ukrainian officials are now urging their populace and Western partners not to play into Putin’s scare tactics. “There are no rose-colored glasses, no childish illusions, everything is not simple. … But there is hope,” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said in a video address on January 25, inadvertently echoing [former Afghan President Ashraf] Ghani in the final days of the war in Afghanistan. “Protect your body from viruses, your brain from lies, your heart from panic.”

Worth Your Time

-

For more on President Biden’s Supreme Court shortlist, check out the latest Original Jurisdiction newsletter from friend of the Advisory Opinions pod David Lat. Why does he think Ketanji Brown Jackson is the runaway favorite? “First, she has the credentials and experience we look for in SCOTUS nominees (for better or worse): two Ivy League degrees; multiple clerkships, including a Supreme Court clerkship; and judicial experience, including service on the prestigious D.C. Circuit and eight years as a district judge before that,” he writes. “Second, she enjoys strong support in liberal and progressive circles, thanks to her background as a former public defender and rulings against Donald Trump and his administration in several high-profile cases—including the Don McGahn subpoena litigation, when she declared that ‘presidents are not kings.’”

-

In their criticism of traditional conservatives and classical liberals, members of the new right often claim to be the only ones speaking to the concerns of Republican voters. But as Noah Rothman points out in a piece for Commentary, ideologues like J.D. Vance, Blake Masters, and Tucker Carlson are increasingly out of touch in their defenses of Russian aggression. One recent Pew poll “found that only 9 percent of Republicans viewed Russia as a ‘partner.’ Thirty-nine percent of self-described GOP voters labeled the country an ‘enemy,’ and a majority called it a ‘competitor,’” he writes. “There’s nothing wrong with advocating unpopular positions you believe best advance American interests. Yet, the nationalist front’s loudest voices never entertain the notion that theirs is a minority view because to do so would be to commit to persuading voters rather than hectoring their fellow conservatives.”

Presented Without Comment

Also Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

Chris’s new Stirewaltisms newsletter has been a pretty strong addition to the Dispatch stable, don’t you think? In yesterday’s edition: The fortuitous timing of Breyer’s retirement, unexpected decency in the wake of the Biden/Doocy flap, the Republican Senate primary in Pennsylvania, mailbag questions, and more. “If this is all done by July, as Hill Democrats are saying, it should be an easy vote for every ‘yea’ and ‘nay,’” he writes of the Supreme Court confirmation process. “This is an election year, though, with potentially open primaries for both parties’ presidential nominations right around the corner. The incentives for stupidity will appear high.”

-

Fan-favorite Charlie Cooke joined Jonah on Thursday’s Remnant for some exceptionally rank punditry about the first year of Joe Biden’s presidency. Which campaign promises has he kept, and which has he not? Why has Biden proven so unwilling to adjust to different political circumstances?

-

On today’s episode of Advisory Opinions, David and Sarah talk about—what else—Justice Breyer’s retirement from the Supreme Court. Who are the leading candidates to replace him? Why is all the talk about Justice Kamala Harris or Justice Michelle Obama a bunch of rubbish? Do we expect any real change in the philosophical composition of the court?

Let Us Know

This will be nowhere near as scientific as a Pew survey, but do you consider current economic conditions to be excellent, good, fair, or poor? Have you benefited more from the tight labor market than you’ve lost from inflation, or vice versa?

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Charlotte Lawson (@lawsonreports), Audrey Fahlberg (@AudreyFahlberg), Ryan Brown (@RyanP_Brown), Harvest Prude (@HarvestPrude), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.