Happy Thursday!

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

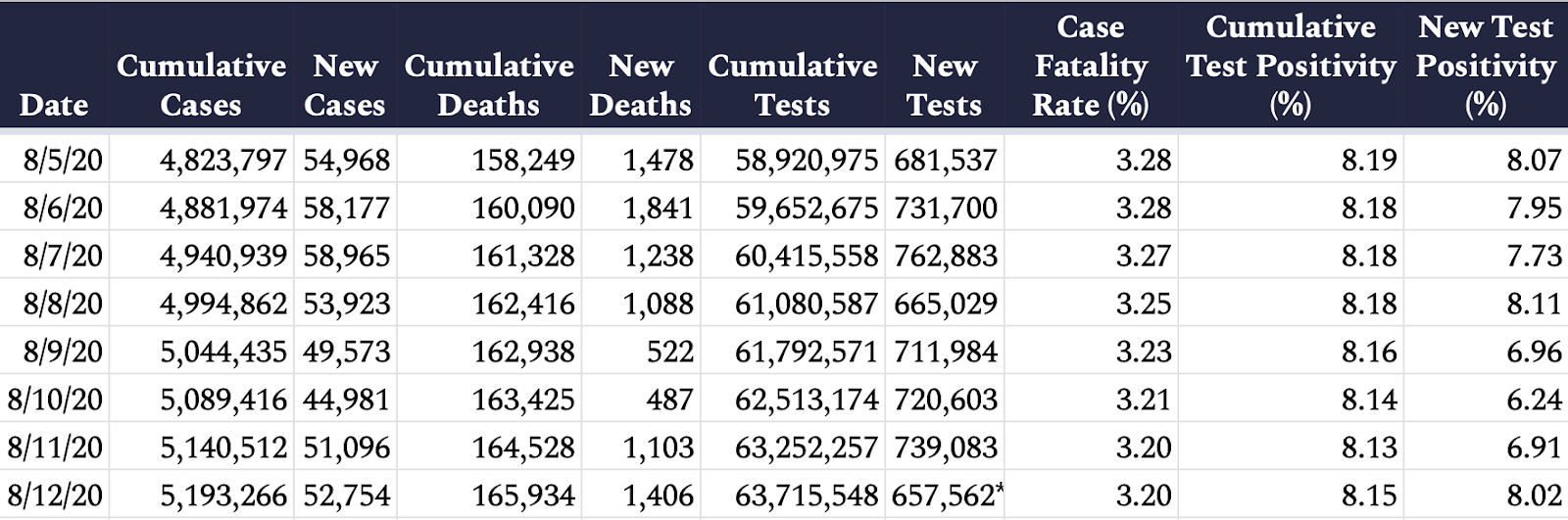

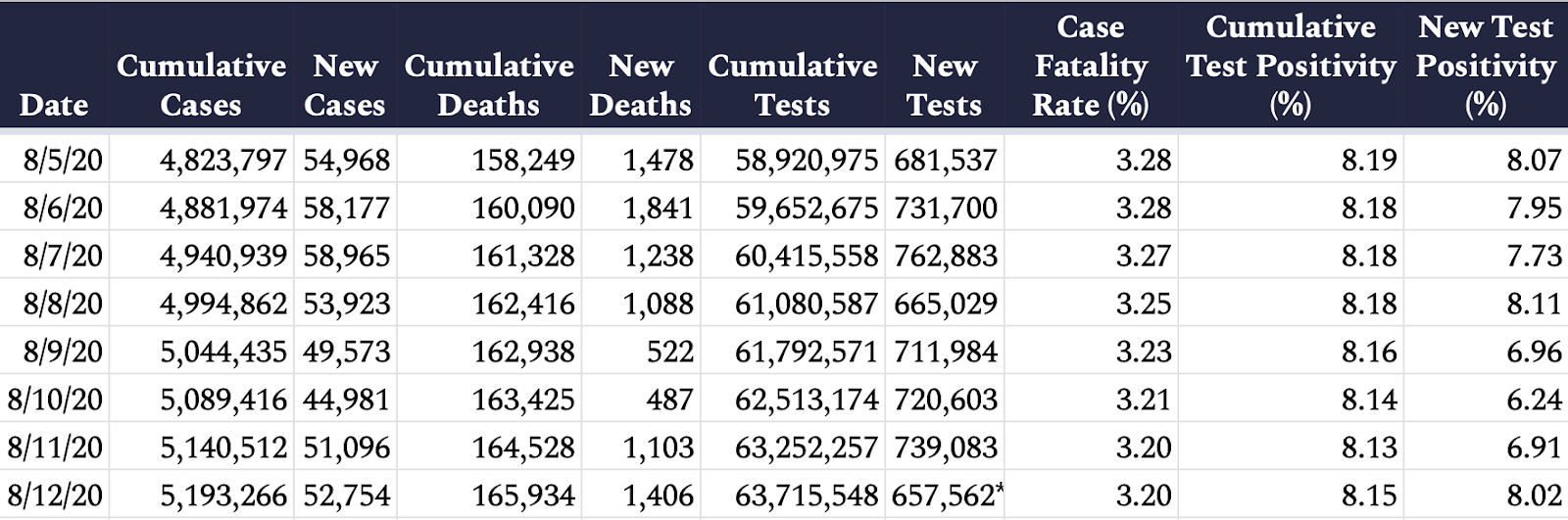

The United States confirmed 52,754 new cases of COVID-19 yesterday, with 8 percent of the 657,562 tests reported coming back positive. An additional 1,406 deaths were attributed to the virus on Wednesday, bringing the pandemic’s American death toll to 165,934. *Note: North Carolina withdrew 220,000 test results due to a reporting error, which explains the discrepancy between cumulative and new tests today.

-

FiveThirtyEight is out with its 2020 election model, which finds Joe Biden has a 71 percent chance of winning the Electoral College compared to Donald Trump’s 29 percent chance.

-

Speaker Nancy Pelosi said Wednesday that Democrats and the Trump administration remain “miles apart” on the next round of economic aid in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

-

The Biden campaign raised a whopping $26 million in the 24 hours after announcing Sen. Kamala Harris would be joining the ticket. Harris appeared with Biden in Delaware yesterday for the first time as his running mate, leaning into her past as a prosecutor, reminiscing on her friendship with Biden’s late son Beau, and previewing the attacks she’ll bring to President Trump and Vice President Pence.

-

Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward has a second Trump administration book due out next month, this one called “Rage” and featuring several interviews with Trump himself. CNN reports that “Woodward conducted more than a dozen interviews with Trump for ‘Rage’ at the White House, Mar-a-Lago and over the phone.”

College Football Hangs in the Balance

The Big Ten, Pac-12, and Big East college athletic conferences officially announced this week they were joining smaller conferences—the Ivy League, the Mid-American Conference, the Mountain West Conference—in postponing all fall sports until spring 2021 at the earliest.

“As time progressed and after hours of discussion with our Big Ten Task Force for Emerging Infectious Diseases and the Big Ten Sports Medicine Committee,” Big Ten Commissioner Kevin Warren said in a statement, “it became abundantly clear that there was too much uncertainty regarding potential medical risks to allow our student-athletes to compete this fall.”

The other three Power 5 conferences—the Big 12, SEC, and ACC, mostly located in the South and Sun Belt—reiterated this week they plan to forge ahead with their football seasons, albeit with modified schedules.

College football has become, well, a political football, in the larger debate over the national coronavirus response. Many high-profile politicians criticized the aforementioned conferences’ decisions to postpone their fall seasons, including President Trump.

Nebraska Sen. Ben Sasse—who served as a university president before running for office—also wrote a letter to the Big Ten presidents and chancellors urging them not to cancel the season. “Life is about tradeoffs,” he wrote. “There are no guarantees that college football will be safe—that’s absolutely true; it’s always true. But the structure and discipline of football programs is likely safer than what the lived experience of 18- to 22-year-olds will be if there isn’t a season.”

This argument—that a disciplined football season would actually be healthier for players than the lack of one—is also what undergirds the #WeWantToPlay movement spearheaded by some of the top players—Clemson quarterback Trevor Lawrence and Ohio State quarterback Justin Fields, among others—after a Zoom call between players from a range of different teams and conferences.

“People are at just as much, if not more risk, if we don’t play,” wrote Lawrence in a Twitter thread Sunday. “Players will all be sent home to their own communities where social distancing is highly unlikely and medical care and expenses will be placed on the families if they were to contract COVID-19. Not to mention the players coming from situations that are not good for them/their future and having to go back to that. Football is a safe haven for so many people. We are more likely to get the virus in everyday life than playing football.”

But many colleges have decided—particularly in the absence of the liability protections Sen. Mitch McConnell has been advocating for in coronavirus relief negotiations—that the risk associated with having a season outweighs the consequences of not having one. The COVID-19 mortality rate for young, healthy men is of course significantly lower than it is in older populations, but with more than 13,000 players across the country, some are bound to have underlying conditions. Dr. Sheldon Jacobson—a computer science professor at the University of Illinois—modeled a full season back and June and estimated 30 to 50 percent of players would contract the virus, and three to seven would die from it.

The liability concerns go both ways. Several top players—Rashod Bateman of Minnesota, Micah Parsons of Penn State—decided to opt out of the season even prior to the Big Ten’s postponement. “I am now making the hardest decision that I have ever had to make in my life,” said Bateman, who is expected to be a first-round NFL draft pick next spring. “I have to set my wishes aside for the wellness of my family, community, and beyond.”

The SEC announced its safety protocols earlier this week, including biweekly testing for all players, mandatory masking and social distancing on sidelines. But with dozens of teams traveling across the country and living on college campuses, the odds of creating a fully impenetrable bubble are slim to none.

The lack of a football season will deal a serious blow to many large college’s budgets, creating shortfalls that will roil athletic departments for years. At some major programs, college football can generate as much as $150 million annually.

Some Flashes of Good COVID News?

Is America past the worst of its second COVID wave? It’s not the sort of thing you want to just blurt out—knock on wood, and all that—but we are starting to see some encouraging signs in the numbers.

After shooting up like a rocket between mid-June and mid-July, new daily cases of the virus have started to dip again over the last two weeks. Daily deaths, a trailing indicator, have yet to follow suit—more than 1,000 Americans per day are still dying from the disease. But while that number is tragic, it’s several times less severe than the daily death totals we were seeing during the virus’ first surge in mid-April—when new cases per day at their worst were barely half what they’ve been in recent weeks.

Why are cases seemingly dropping? One reason may be because testing itself has dipped a bit since August. But while that isn’t ideal, it doesn’t account for the full dip either—the test positivity rate has continued to inch down, too, suggesting that a slight ebb in tests hasn’t hurt our ability to see the state of the virus today.

A clue can be found in a recent National Bureau of Economic Research paper that tracked consumer behavior in the days during and immediately following our national lockdown this spring. By examining data from SafeGraph and Yelp, the researchers deduced two interesting facts: Beginning state lockdowns actually had a smaller-than-expected impact on consumer behavior, because people were already choosing to steer clear of public spaces anyway. But ending state lockdowns had a much more sudden effect: People surged back into public spaces, even in places where it was not yet actually safe to do so.

“Lifting these bans can have both a direct effect—people who always wanted to do the activity can do so—and an indirect effect—the lifting of the regulation sends a signal suggesting that the activity is now safe,” the paper reads. “Neither the model nor our empirical work suggests that reopening was necessarily a good or bad decision, but it does suggest consumers interpreted states’ reopening decisions as a signal that the risk had abated, even in states where that does not appear to have been the case.”

What this suggests is that the spike that followed economic reopenings may not have been a necessary consequence of reopening—rather, it was a consequence of reopening in an environment where a critical mass of people felt the danger was past. Two months and thousands of deaths later, many of us have been disabused of that notion.

As we mentioned yesterday, fully half of Americans now personally know someone who has had COVID-19, with one-fifth of Americans knowing someone who has died from it. It could be that cases are slowing again simply because enough of us have been personally affected by the virus that we’ve resolved to get serious about it again.

Why have deaths not been as bad this time around? One grim reason seems to be because of how badly we failed before at keeping the virus out of communities where it was poised to do the most damage, like nursing homes. Some of this was simply due to the virus catching us unawares and flat-footed, such that it had spread many places back in March before we started any protective measures. Then there were specific major policy failures, like New York’s decision on March 25 to return recovering COVID-19 patients from hospitals to nursing homes. The flip side of this is that while the virus has spread more widely in recent months, we’ve done a better job keeping it out of those extreme high-risk environments.

Then there’s the matter of treatment. While there’s still no cure or universally effective treatment for the virus, doctors and hospitals now have months of experience under their belt, during which time a worldwide effort to throw the kitchen sink at the problem has paid some dividends. A number of treatments have emerged to nibble around the edges of the pandemic—antivirals, steroids to soothe inflammation and prevent a patient’s immune system from running amok, blood thinners to guard against surprise side effects from COVID’s tendency to clot the blood. Then there’s convalescent plasma: The more people recover from the virus, the more there are to donate the antibody-laden blood serum to those still suffering.

We’re nowhere near out of the woods yet. But it’s not all despair out there. Keep the faith.

Worth Your Time

-

Just hours after Marjorie Taylor Greene—the QAnon adherent with a history of bigoted comments—won her primary in Georgia’s 14th Congressional District, President Trump tossed his full support behind her, calling her a “future Republican Star” and a “real WINNER!” Melanie Zanona, Ally Mutnick, and John Bresnahan have some great reporting at Politico on the headaches Greene is already causing Republican officeholders—and Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy in particular. A source close to McCarthy told Politico that he would welcome Greene into the GOP conference if she wins in November, something that appears likely given the strong GOP makeup of her district. “Kevin McCarthy puffed his chest out about stripping Steve King of his committee assignments, then sat on the sidelines and let another Steve King walk away with this race in GA14,” said one GOP source. “It’s political malpractice and Republicans will be answering for her for years to come.”

-

FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver wrote a piece—“It’s Way Too Soon To Count Trump Out”—explaining how his election model works, and it’s a really useful guide to polling, probability, and campaign fundamentals. “Biden is in a reasonably strong position: Having a 70-ish percent chance of beating an incumbent in early August before any conventions or debates is far better than the position that most challengers find themselves in,” Silver writes. “His chances will improve in our model if he maintains his current lead. But for the time being, the data does not justify substantially more confidence than that.”

-

It’s certainly true that today’s cultural climate has made it all too easy to denigrate history for its failures and take progress for granted. “The idea of the past as nothing but a nightmare, specifically one of injustice, is probably the prevailing historiographical trope of our time,” writes Theodore Dalrymple in Law & Liberty this week. He advocates for a “historiography that is capable of recognising defects and even horrors in a tradition, but also strengths and glories, such that the tradition can survive without remaining obdurately stuck in its worst grooves.”

Presented Without Comment

Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

Joe Biden tapped Kamala Harris as his running mate on Tuesday, and The Dispatch Podcast gang (with Declan filling in for Jonah this week) has thoughts. Tune in for a lively discussion on what Biden’s VP pick means for the future of the Democratic Party, a deep dive into foreign election meddling, and a much-needed update on the status of professional sports during the pandemic.

-

Speaking of foreign election meddling, Thomas Joscelyn’s latest Vital Interests newsletter (🔒) asks and answers the question: How effective is Russia’s disinformation? Spoiler: Not as effective as you might think.

-

Social conservatives are sounding the alarm over a new rap song called “WAP” by Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion over its explicit language and sexual innuendo. It reminds David of another rap song from years ago that created a stir, 2 Live Crew’s “Me So Horny.” In yesterday’s French Press (🔒), he looks back on how efforts to combat the song—the song was banned in some places, and the group was arrested for performing it live—failed, and the risks inherent when “political power was brought to bear in the attempt to rescue the culture.”

Let Us Know

Is your favorite college football team still scheduled to have a season this fall? Do you agree with where they landed?

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Charlotte Lawson (@charlotteUVA), Audrey Fahlberg (@FahlOutBerg), Nate Hochman (@njhochman), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Photograph by David John Griffin/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.