Happy Wednesday. April Fools’ Day is canceled, due to coronavirus concerns.

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

As of Tuesday night, there are now 189,035 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the United States (a 15.1 percent increase from yesterday) and 3,900 deaths (a 23.3 percent increase from yesterday), according to the Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, leading to a mortality rate among confirmed cases of 2.1 percent (the true mortality rate is difficult to calculate due to incomplete testing regimens). Of 1,048,971 coronavirus tests conducted in the United States, 17.6 percent have come back positive, per the COVID Tracking Project, a separate dataset with slightly different topline numbers.

-

Asian countries that had gotten ahead of the coronavirus spread are instituting new, strict rules to prevent a resurgence.

-

Democratic frontrunner Joe Biden said Tuesday evening that it was difficult to envision the Democratic National Convention taking place as planned in Milwaukee this July.

-

Bill Gates, who has been warning about pandemics for years, lays out his plan for this one. “There’s no question the United States missed the opportunity to get ahead of the novel coronavirus. But the window for making important decisions hasn’t closed.”

-

The Department of Justice Office of the Inspector General issued its long anticipated FISA report on Tuesday, finding that every one of the 29 FISA applications it reviewed had errors, inadequately supported facts, or in four instances, supporting files that could not even be located.

-

The stock market closed out one of its worst quarters in recent memory yesterday. The Dow dropped 23.2 percent over the past three months, and the S&P 500 fell 20 percent.

‘This Is Going to Be a Very, Very Painful Two Weeks’

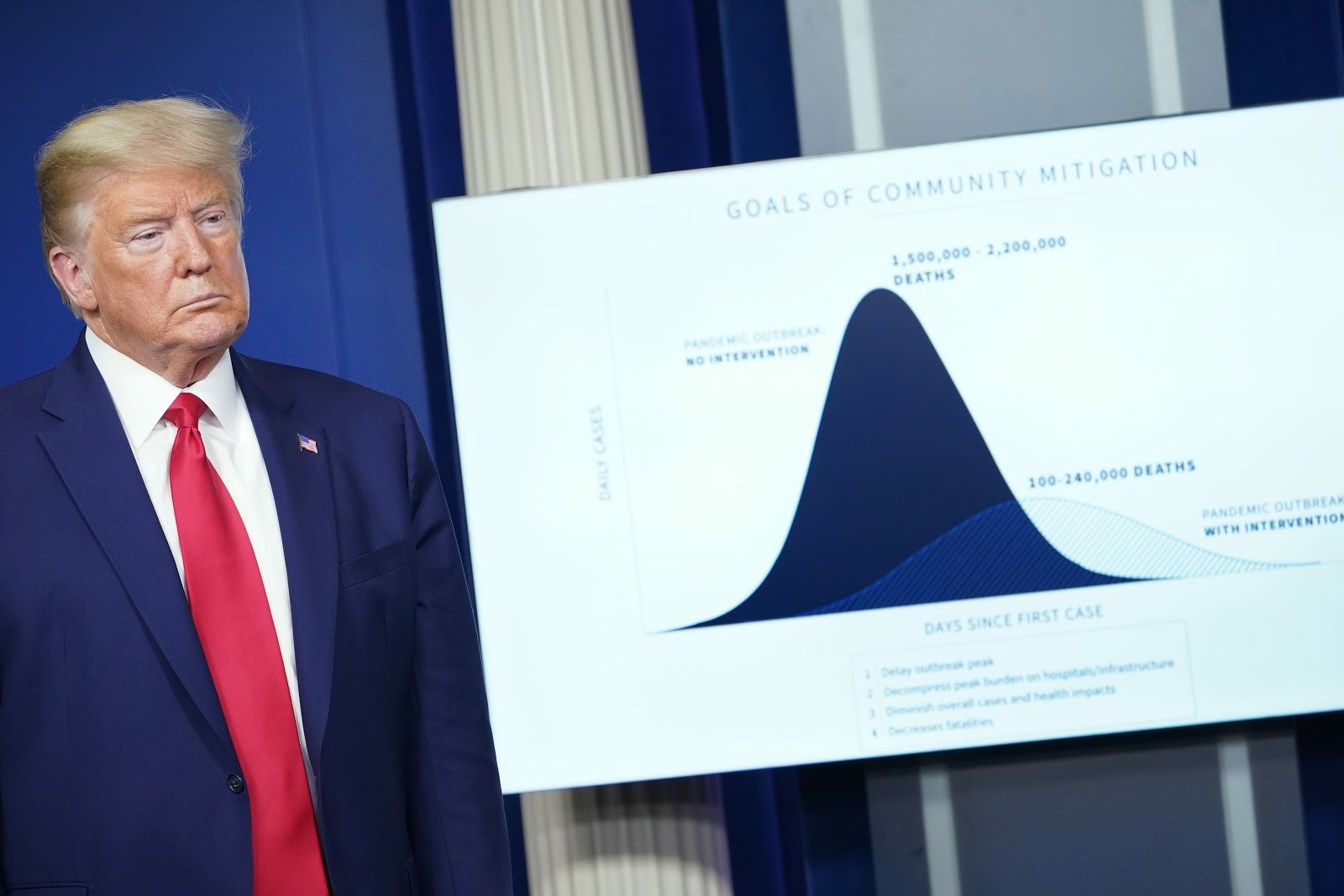

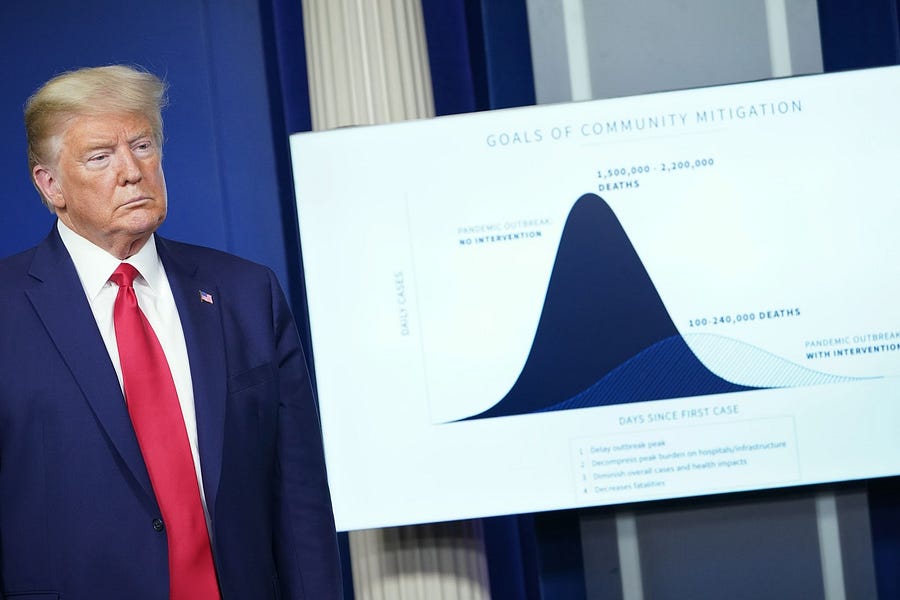

At a marathon White House press briefing Tuesday, President Trump and his administration’s top pandemic experts had a bracing message for the country: We’re about to start seeing many, many more coronavirus deaths, and if we’re lucky, the next two weeks will be the worst.

“I want every American to be prepared for the hard days that lie ahead,” Trump said, with uncharacteristic solemnity. “This is going to be a very, very painful two weeks.”

The numbers the experts shared were certainly painful: 100,000 to 200,000 deaths over the next few months even if things go well, according to one model shared by Dr. Deborah Birx, the White House’s coronavirus response coordinator.

Yet Birx, Dr. Anthony Fauci, Trump, and Vice President Mike Pence assured the nation that many signs remain encouraging: Outside of New York and New Jersey, most metropolitan areas are showing substantially slower case growth, raising the possibility that hotspots could remain rare and the final death tally could end up being less disastrous than projected.

“Models are as good as the assumptions you put into them,” Fauci said. “As we get more data as the weeks go by, that could be modified.”

Much of the responsibility for keeping that number low will continue to fall on the response of the federal government, as it continues to try to catch up with widespread testing, logistical coordination, and crisis care. But both Fauci and Birx stressed that nothing is currently playing a bigger role in slowing the spread than the continued diligence of the American people.

“It’s communities that will do this,” Birx said. “There’s no magic bullet. There’s no magic vaccines or therapies. It’s just behaviors.” Fauci added that it’s “not time to take your foot off the accelerator” of stringent social distancing measures, “but to just press it down.”

The graveness of the situation seemed to impress itself on president and media alike in the briefing room: As Trump fielded media questions for the better part of two hours, the back-and-forth rarely devolved into the sort of mutual antagonism that frequently overwhelms such briefings.

Meanwhile, the CDC is currently reevaluating whether to reverse a key part of its own early COVID-19 guidance: recommending that even healthy people wear masks in public spaces where they could come into contact with others.

As the novel virus began to take hold around the world earlier this year, U.S. health systems saw at once that getting enough protective equipment for their medical professionals was going to become a significant problem. Early CDC mask guidance was designed to prevent a run on the national supply: stressing that wearing a mask didn’t help keep a person healthy and advising that people shouldn’t wear them in public unless they were symptomatic themselves.

But masks can be extremely useful in preventing unwitting spread to others when worn by those infected. So as the virus’s rampant community spread has illustrated the problem of asymptomatic carriers, the CDC has begun to consider whether the best way to mitigate the issue is a blanket mask policy. “The CDC group is looking at that very carefully,” Fauci said Monday.

On Tuesday afternoon, Trump encouraged people who wished to mask themselves that improvisation was an acceptable tactic: “I would say do it, but use a scarf if you want, rather than going out and getting a mask or whatever.”

The Remarkable Parallels Between 1918 and Today

Each and every day of this pandemic may feel like it’ll take up an entire chapter in a future history textbook—and the crisis stands to become the defining event of a generation—but that doesn’t mean any of this is unprecedented. We pored over newspaper clippings from a century ago in search of similarities and differences between the Spanish flu and what we’re living through today. What we found was eerily reminiscent of the last three weeks.

“Queer Ailment Gripping City,” read the headline of one of the earliest pieces on the virus in the Detroit Free Press. “No section of Detroit spared by epidemic of malady resembling influenza. Whatever it is, you’ll know if you’ve got it. … Some physicians profess to note in the ailment a marked resemblance to genuine old influenza. Others assert it to be in the nature merely of a severe cold aggravated by infections from germ-laden dust on the city streets. Dr. W.K. Kwiecinski, a leading Polish practitioner, states that the disease, as it is in evidence among his patients, has all the earmarks of bronchial pneumonia and is spreading at an alarming rate.”

On September 14, 1918, the New York Times reported on then-Surgeon General Dr. Rupert Blue’s description of the disease and its treatment: “‘First there is a chill, then fever with temperature from 101 to 103, headache, backache, reddening and running of the eyes, pains and aches all over the body, and general prostration. Persons so attacked should go to their homes at once, get to bed without delay, and immediately call a physician … Treatment under direction of the physician is simple, but important, consisting principally of rest in bed, fresh air, abundant food, with Dover’s powder for the relief of pain. Every case with fever should be regarded as serious, and kept in bed at least until temperature becomes normal.’”

Less than a month later—on October 5—Dr. Blue argued the only way to stop the epidemic was to shutter churches, schools, theaters, and public institutions in every community in which the virus was present, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported. “‘There is no way to put a nation-wide closing order into effect,’ said Dr. Blue today, ‘as this is a matter which is up to the individual communities. In some states the state board of health has this power, but in many others it is a matter of municipal regulation. I hope that those having the proper authority will close all public gathering places if their community is threatened with the epidemic. This will do much towards checking the spread of the disease.’”

There were fights over how much of the economy to shutter. “We should close all stores and all places of business except food stores and drug stores,” City Physician W.C. Goenne told the Daily Times of Davenport, Iowa. “If such a quarantine were placed on the city for a week I believe we could stop the epidemic. I do not believe in partial quarantine, however.”

But Charles Grilk—the chairman of Davenport’s chapter of the Red Cross—disagreed, arguing it would be impossible to enforce such restrictions and that the community should simply isolate the sick. “I believe that the epidemic will run its course,” he said. “I am in favor of quarantining the individual cases.”

The acting mayor of Tucson, Arizona, ordered all public places in the city closed on October 10, including “churches of all denominations, public and private schools, moving picture houses, [and] pool rooms.” He concluded: “I urge upon every person, above named places of assemblage and all ministers of the gospel to strictly observe this request. We are not only fighting the enemy abroad [referencing World War I, which was coming to a close but still raging], but also the enemy at home. In order to conserve all our forces and resources it becomes a necessity for each and every one to observe this request.”

An Associated Press story that same day reported the “Spanish influenza now has spread to virtually every part of the country.”

The Journal and Tribune in Knoxville, Tennessee, cited Boston health authorities’ tips for avoiding infection: “Keep out of places where people are. Do not let anyone cough, etc., into your face. Keep your mouth shut. Wash your hands frequently. Avoid getting tired—go to bed early. Eat your meals regularly and slowly. If compelled to eat away from home, see that the dishes and cups are clean. Keep where the air is fresh.”

About 10,000 posters were plastered around New York City. “To prevent the spread of Spanish influenza, sneeze, cough, or expectorate (if you must) in your handkerchief,” they read. “You are in no danger if everyone heeds this warning.”

On October 12, the Buffalo Times reported local health commissioners “suggested that every person in the city should wear a mask for nose and mouth … ‘If everyone in the country would go masked at all times the epidemic would be conquered in the United States in a week to ten days,’ declared Dr. Charles G. Stockton.”

But there weren’t enough masks to go around in many parts of the country. “An emergency call was made for the Red Cross to make 1,200 masks for the boys in camp as a preventive from the Spanish flu,” reported the Adams County Free Press on October 16.

Articles were written decrying the economic effects of local quarantines. “The dreaded Spanish ‘flu’ has numbered among its victims scores of Des Moines business men whose names will not be mentioned in the reports of the health department,” the October 3, 1918, Des Moines Register read. “In fact, practically every owner of a movie show, restaurant, temp bar, dance hall, taxicab or other place of business which has catered to the boys in khaki claims that the ‘flu’ has hit him hard, since the quarantine of Camp Dodge and Fort Des Moines went into effect.”

“‘How’s business? Rotten!’ say the taxicab and bus drivers. ‘Several of the boys have quit, and lots more of us are thinking about it. The traffic ain’t paying for the wear on tires.’”

Lawmakers came down with the disease—“Senator [William] King of Utah is the first Senate member reported ill with Spanish influenza … [and] has been confined to his home since Sunday”—and the National Association of Motion Picture Industries decided to “discontinue all motion picture releases after October 15 because of the epidemic of Spanish influenza.”

Newspapers ran various advertisements purporting to keep customers safe from the pandemic. “Look out for Spanish Influenza. At the first sign of a cold take Hill’s Bromide Cascara Quinine,” read one. “The dangers of contracting Spanish Influenza can be greatly reduced by having your clothes dry cleaned regularly; Let us be your cleaner,” implored another.

The surgeon general put out a call to physicians in “localities far removed from the districts in which the disease is raging” to travel to where the need was more acute, and New York Health Commissioner Dr. Royal Copeland warned of hospital capacity being strained. “If the prevalence of influenza increases to any degree,” he said, “it will be manifestly impossible to provide hospital care for any considerable proportion of the cases, and the general hospitals will have to be depended on to assist.”

There were even debates over what to name the virus. “Although the present epidemic is called ‘Spanish influenza,’” noted a piece in Missouri’s Wentzville Union on October 11, 1918, “there is no reason to believe that it originated in Spain. Some writers who have studied the question believe that the epidemic came from the Orient and they call attention to the fact that the Germans mention the disease as occurring along the eastern front in the summer and fall of 1917.”

Sounds exceedingly familiar, doesn’t it? This by no means indicates the outcomes of the two pandemics will be comparable—675,000 Americans died from the virus a century ago—but the public responses certainly followed similar patterns. Thankfully, today’s coronavirus does not appear to affect children the same way the 1918 H1N1 virus did, and medicine and technology have progressed mightily in the past 100 years.

Worth Your Time

-

National Review’s John McCormack has a good interview with Sen. Tom Cotton, a China hawk who was sounding the alarm on the threat of the coronavirus long before the rest of the nation was paying much attention.

-

Larry Hogan, the Republican governor of Maryland, and Gretchen Whitmer, the Democratic governor of Michigan, co-wrote a Washington Post op-ed this week with a checklist of things state governments still need from Washington in the weeks ahead to keep the fight against coronavirus going. It’s a little wonky and a little press-release-y, but still worth a read to get a sense of how state authorities are feeling at the moment.

-

He was convicted of murdering his wife on questionable evidence. Now, Joe Bryan has been released on parole 33 years later. ProPublica published an article exploring the history of his case and the flaws in his conviction.

Presented Without Comment

Something Useful

With COVID-19 transmitting rapidly and untraced in communities across much of the country, more and more medical experts are speaking up about the importance of regular people wearing masks while out and about. With hospital-grade respirators in desperately short supply and even regular paper masks hard to come by, that means the best solution for many people is a DIY strategy. This New York Times piece has a good rundown of the available options. As most of your Morning Dispatchers are shiftless men in their 20s, we particularly appreciated this janky option requiring no sewing: just a T-shirt and scissors. (Just remember to launder them: A dirty mask can be worse than no mask at all!)

Toeing the Company Line

-

David’s midweek French Press is a riff on the legal axiom “bad facts make bad law,” arguing that “irresponsible exercise of civil liberties”—such as pastors holding crowded worship services in defiance of shelter-in-place orders—”all too often leads to the cultural and political devaluation of those liberties and—ultimately—to the suppression of those liberties.”

-

The latest episode of The Remnant reunites Jonah with an old wingman, National Review’s Jim Geraghty, to talk the latest on the coronavirus.

-

On the website today Jeryl Bier makes the case for why we should not believe the official numbers coming out of China. “Over the last half of March, despite the massive dispersion of Chinese citizens from the epicenter of the virus, Wuhan, the commission has reported barely one new domestically acquired case per day.”

-

Also on the website, Danielle Pletka surveys a handful of legislative proposals aimed at China—measures to shift the U.S. supply chain away from China, bills regarding Huawei, sanctions regarding the South China Sea—and argues that an comprehensive solution would work better than such piecemeal measures.

Let Us Know

Yesterday, we asked you to share with us the one thing that—were it restored—would make these next several weeks so much easier. Thanks for all your replies, here were some of our favorites.

-

Lydia: The gym. I miss the gym most of all.

-

Rob: Cubs baseball definitely would make this better.

-

NYerInExile: What my wife and I are currently missing the most is our ability, as Catholics, to celebrate the Mass in person with our parish, and most importantly, to receive the Eucharist.

-

Tina: I miss going to the library. Selecting and reading hardcover books.

-

James: What I miss most is dining out with my wife once or twice a week. I suspect that sounds shallow to many, but it has been an integral part of our routine.

-

Susan: I am a docent at a botanical garden here in Arizona, where it is the height of spring. I miss being in the garden and introducing people to the beauty of the desert.

-

David: One thing I’ll never take for granted again: the dog park!

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Alec Dent (@Alec_Dent), Sarah Isgur (@whignewtons), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.