Appetizer

What is going on with the GOP presidential primary polls? From Nate Cohn at the New York Times:

In national surveys since last November’s midterm election, different pollsters have shown [Trump] with anywhere between 25 percent and 55 percent of the vote in a multicandidate field.

That’s right: a mere 30-point gap.

As Nate pointed out in 2019—when he predicted that Joe Biden would be the frontrunner for the Democratic nomination the next year, months before Biden was even officially in the race—these polls can be predictive.

“Across both parties, candidates who have led in the polls over the first six months in the year before the primary have gone on to win more than half the time since the modern primary system developed in the early 1970s,” he wrote. Reagan in 1980, Bush in 1988, Bush in 2000, Gore in 2000, Kerry in 2004, Romney in 2012, Clinton in 2016, and Biden in 2020 all fit the pattern.*

With the polls all over the place this time around, how do we know whether Trump is the strong frontrunner or in a touch-and-go with Ron DeSantis? From a pure logic standpoint, it’s possible that none of the polls are right but surely we can figure out which ones are definitely wrong?

It’s worth reading all of Nate’s reasoning—and I think there are plenty of pollsters who would quibble with an item or two on his list—but this is where he comes out:

“There are two reasons to err toward the polls that are showing Trump weakness. First, the so-called probability polls have uniformly showed relative weakness for Mr. Trump … Second, the state polling is almost entirely consistent with a weak or relatively weak Trump … The assessment that Mr. Trump is stuck in the low-to-mid 30s nationwide represents a best guess.”

There are other warning signs for the Trump team. His fundraising numbers are abysmal. His campaign committees reported raising only $9.5 million since launching in November, leaving him with $25 million in the bank. Last year, he reported more than $100 million at the start of the year. These numbers are all the more shocking when you consider what a fundraising juggernaut Trump once was, raising more than $200 million in the month after the 2020 election.

And then there are the other guys. In the last week, Trump has tried to land attacks on Chris Christie, Nikki Haley, and DeSantis. But it all feels so different from 2015, when a Trump attack dominated the headlines and forced every candidate to play on his field. It feels much less like Trump is at the steering wheel this time. DeSantis isn’t expected to announce until after Memorial Day and that feels much more like the starting gun instead.

Trump isn’t where he was in 2015, but he isn’t going to run out of money. And he will never truly lack for attention. Even Cohn’s analysis leaves Trump as the marginal frontrunner in these polls, and that is a good place to be historically.

Entree

If you know anything about the history of redistricting law or the politics of race in this country, this is a monumental statement in a piece from Josh Kraushaar in Axios this week: “Of the 60 Black lawmakers elected to Congress this year, 30 now represent states or districts with a plurality of white voters, according to an Axios analysis. … In 2014, only eight (of 43) elected Black lawmakers were from plurality-white states or districts.”

This is great news for the racial progress of the country. But there’s a lot more at stake politically.

First of all, our redistricting laws are a bit of a mess when it comes to race. Politicians would “crack” minority neighborhoods and scatter them into other districts to dilute their voting power or “pack” minority neighborhoods into as few districts as possible to have as few minority representatives as possible. The Supreme Court has traditionally struck down such racial gerrymanders as violating the Voting Rights Act. But by forbidding cracking and packing, the court has by definition also required states to use race as a determining factor in drawing district lines, and that itself could be seen as a violation of the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

The Supreme Court is considering this exact question this term. Of Alabama’s seven congressional districts, only one is made up of a majority of black voters, even though more than a quarter of Alabama’s voters are black. Alabama says they used race neutral principles to draw the lines. The challengers say that’s not the question; minority groups must be able to elect representatives of their choice, which requires the state to consider race as a factor.

The VRA requires minorities to have the same “opportunity as other members of the electorate to participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice.” But what if race is no longer a predictive factor in who a district elects? What if a district that is 4 percent black can regularly elect a black representative? Texas 23rd, for example, is 70 percent Hispanic and elected Will Hurd three times. Georgia’s voting population is 29 percent black and 53 percent white and elected one black senator and one white senator.

Second, in the past, these “majority minority” districts were by definition almost always safe seats for whomever held them. On the one hand, that gave these members the longevity to build seniority. On the other hand, it also limited their political power since they never got to showcase their skills at winning tough races in swing districts, which was often the path to statewide office and party relevance. Val Demings, who was on Biden’s VP short list and the Democrats’ 2022 Senate nominee in Florida, was elected in a plurality white district. I’d argue it’s no coincidence that neither of our two most prominent black politicians, Barack Obama and Kamala Harris, began their careers in the House in majority-minority districts even though both California and Illinois both have plenty. (On the other hand, I should note that House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries was elected in a majority black district that favors Democrats by 26 points.)

Third, it’s also possible to read this data quite differently. Perhaps it’s not that racial attitudes have evolved but that partisanship has simply overtaken it. And maybe that’s not an unqualified good. “Vote blue no matter who” may be an old rallying cry on the left but it may be more true than ever. When the only thing voters care about is the letter after someone’s name—over their experience, their qualifications, or whether they share the same community—maybe we end up with even more negative partisan polarization. And there’s some evidence to bear this out, as well.

In 1958, 44 percent of whites said they would move if a black family became their next door neighbor and only 4 percent approved of an interracial marriage. Now, it’s hard to even find data on the first question because the number dropped below 1 percent by the late ‘90s, and 94 percent now approve of marriages between white people and black people. All of this is great news.

But in the meantime, I’m not sure we’re actually getting along any better.

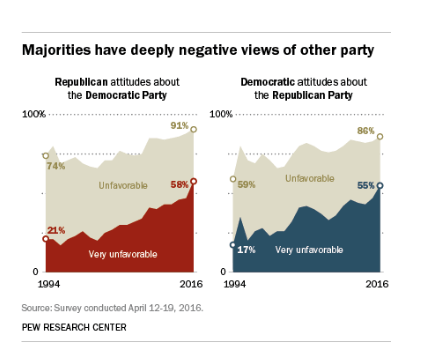

About 70 percent of Democrats say they probably or definitely would not consider being in a committed relationship with someone who voted for Donald Trump. More than 4 in 10 Republicans say it’s harder to get along with a liberal neighbor—political ideology was more important than sports, church attendance, military service, kids, or sexual orientation. Half of Republicans and Democrats say that the other party makes them feel angry and afraid. More politically engaged members of both parties are closer to 70 percent. And the trend lines aren’t good.

Plenty of studies are finding that “the strength of people’s attachment to their political parties surpasses affiliations with their own race, religion and other social categories” and “party affiliation now plays a bigger role in determining a person’s overall political views than their race, class, religious beliefs or education level.” In fact, David French wrote a whole book about it, which I highly recommend. In many, many ways, politics has become our new religion. But unlike the post-Henry VIII game of thrones between the Catholics and Protestants, we hold a vote on which new religion will be in charge every two years.

Two takeaways here: America is becoming a more racially diverse, tolerant, and representative place. But at the same time, we are also becoming less tolerant, more fearful, and more polarized along other lines. Maybe we could work on that one too?

Dessert

The Great Sort continues. Honestly, this chart probably says more about political polarization than anything any of us have written in the last 20 years. And now I’m craving some smothered and covered.

*Correction, February 13: This newsletter incorrectly included Bill Clinton in 1992 among the list of presidential candidates who have led in the polls for the first six months of the year before primaries began.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.