Welcome to the August doldrums. In presidential campaign world, this month can feel like one of those 19th century military encampments as troops amass, polishing their weapons around the campfire at night, feeling the battle will start in just a few weeks. Everyone from the campaign manager to the lowest field staffer knows that this is their last chance to steal a nap, have dinner with a cloth napkin, or take a luxurious 15-minute shower without being forced to turn off the water to answer the phone with soap still in their hair (ahhhh, burning memories … literally!).

Starting in September, the battalion will be in a dead sprint to charge Election Day Hill and the war will be in full swing.

But there is one exception. This feeling of impending doom/excitement/anticipation lasts a lot longer for the lawyers. Like so many children during their 1950s duck and cover drills, these lawyers prepare for months for a day that is perpetually unlikely to happen: a multi-front recount. Will this year be different?

We’ll also take a quick look at the primaries from this week and what we learned. There are 85 days left. Let’s dive in!

Campaign Quick Hits

Debating the debates: The Commission on Presidential Debates declined to add a fourth debate in September at the urging of the Trump campaign, which argued that a debate was needed before mail-in ballots were sent out. In a public letter to the campaign, the commissioners explained, “There is a difference between ballots having been issued by a state and those ballots having been cast by voters, who are under no compulsion to return their ballots before the debates. In 2016, when the debate schedule was similar, only .0069% of the electorate had voted at the time of the first debate.”

Vaccine partisan gap: Fewer than half of Republicans—47 percent—in a Gallup survey said they would get “an FDA-approved vaccine to prevent COVID-19 … at no cost.” Only 19 percent of Democrats said they would not get the vaccine. When each side is messaging to its own voters about the pandemic, operatives are going to stare long and hard at numbers like these.

Ad wars cont’d: It’s worth noting that reserving ad time is a good press release parlor trick for campaigns. The announcement captures headlines but the campaign can always pull back the reservation at any time, or add to it. Here’s a great example of a headline that doesn’t matter: “Joe Biden’s Democratic presidential campaign is reserving $280 million in digital and television ads through the fall, nearly twice the amount President Donald Trump’s team has reserved.”

Supreme Court ticks up as issue for Democrats: I had an inkling when I saw this sign in D.C., which said “If you won’t wear a mask to protect your friends and family, do it to protect RBG.” Lo and behold, Morning Consult found that “57% of Democratic voters say the Supreme Court is very important, up 9 points since May. 53% of GOP voters say the court is a very important factor in their vote, unchanged since the spring.”

Mail-in ballot debacle: Of the 403,103 mail-in ballots that the New York City Board of Elections received for the Democratic presidential primary, 84,108 were rejected. That means 21 percent of Democrats who tried to cast a vote in the June primary were disenfranchised. Whether to count some of the ballots that lacked a vaid postmark is on appeal. And we still don’t know who won.

Kanye and the birthday party: Kanye West won’t be on the ballot in 21 states as of now. But Colorado voters will be able to pick him; Ohio and Wisconsin might as well. Who does that help? A newsletter for another time.

Of Killer Whales and Recounts

In early 2012, Sasha Issenberg, who would go on to write The Victory Lab: The Science of Winning Campaigns, published a story about a new project within the Obama campaign code-named Narwhal. As he put it, “Obama’s team is working to link once completely separate repositories of information so that every fact gathered about a voter is available to every arm of the campaign.” This was the precursor to the kind of voter modeling and scoring we discussed last week.

But several hundred miles east of Chicago, in a cozy stout office just a few blocks from Paul Revere’s house nestled among the patriotic landmarks of downtown Boston, the senior brass of the Romney’s political department were discussing narwhals as well … and what ate them. Thus was born the catastrophe that was Project Orca.

In evolutionary terms, Project Narwhal was that first dinosaur that found itself with a wishbone able to propel its downy feathered wings. It thrived against its predators at the time, its progeny survived the asteroid (the 2016 election), and it is now the ancestor to the buffet of species of birds that we see today (voter scoring and modeling). On the other hand, Project Orca was the dodo bird—an evolutionary dead end that’s hard to even explain why anyone thought it was a good idea.

Why do I bring all this up?

For one, it’s a lovely stroll down memory lane for me. For those of you who volunteered on the Romney campaign eight years ago, just the mere mention of orcas is probably enough to send you into convulsions. I was in the field for the last several months of the 2012 election as part of the legal team. I was told this was going to be a tool for our field lawyers to be able to track Election Day incidents and deploy to hot spots more efficiently. But how? It became clear to everyone except the people touting it that their version of how this would all transpire made no sense and wouldn’t work regardless.

The idea was good in theory but never made sense in practice. Of course, that was one of the biggest problems—there was no time to practice. The app—to the extent one can call it that—rolled out the day of the election. But who am I kidding? The idea didn’t make sense either. It relied on volunteers, many of them elderly, to download an app on their phone the morning of the election (never mind that back then most of them still had flip phones). They would have to check off names from the voter rolls as people came into vote, and alert the legal team when they had a problem by pressing a button on the app that I can only assume said “Better Call Saul.” If all of these things happened, the political team would know who had already voted and be able to target supporter-not-yet-voted people from the voter file later in the day with targeted messages, phone calls, etc.

To the lawyers on the team, it was never even really a “plan” so much as “a picture of a dumpster on fire.”

As it was reported in the press and despite our warnings, the whole thing went down the day of the election. But that isn’t quite true. That implies it went up first. In fact, it never happened at all. I had 200 lawyers in a room in Richmond, Virginia, and by 7a.m., we were using landlines and paper. To this day, I’ve never seen the app. Speaking of things that didn’t happen, we also had a private plane waiting on a runway outside of D.C. waiting to take our army of lawyers to wherever the recount would turn out to be. (I still used my “go bag” that I had packed for the plane—to live on a friend’s couch with the shades drawn surviving on hummus, red wine, and her HBO subscription.)

So why didn’t anyone listen to the lawyers? It may not surprise you to learn that lawyers aren’t very high on the social status totem pole of campaigns.

To put this in ’90s high school rom-com terms: The political department is home to the jocks—lovably crushing beer cans on their foreheads while talking about the rager they don’t remember from last weekend. The finance folks are the cheerleaders—popular and beautiful and dating some guy in college that you don’t know. The communications department is where the student council stars land, all put-together and ambitious, if a little suspect because they are notoriously buddy-buddy with the teachers. And then there’s the poor lawyers—hopelessly stuck in the band room while they devise a great diorama for fourth-period biology that involves worms. Sure, the cooler kids know they need to be nice enough to the band geeks—how else are they going to pass biology?—but they don’t want to be seen with them in the hallways.

Back to the point: Lawyers perform a few vital functions on campaigns.

First, there’s the general counsel/HR side. Campaigns are multimillion dollar startup businesses that have all the personnel drama of any other business (maybe more so). People get hired and fired and reprimanded and crash their rental cars. There’s incorporation issues and taxes and copyrights. Leases, venue contracts, and insurance.

Second, there’s the election law part. As Kanye can now tell you, a candidate doesn’t automatically wind up on 50 state’s ballots without a lot of leg work. And then there’s the “keep us out of jail” stuff. The campaign can’t “coordinate” with a super PAC but is it coordination if the campaign creates an unpublicized but publicly available Twitter account that happens to tweet out internal poll numbers showing which media markets they are most competitive in? Or how about the super PAC posting its entire trove of opposition research—which costs hundreds of thousands of dollars to create—online for free?

Third, there’s litigation. This is the phase we are in right now. And I’m always stunned with how little attention it receives in comparison to its relative importance. As I noted in quick hits above, reserving TV air time is a largely made-up number that is an instant sugar high for campaign reporters. But filing an injunction to extend the deadline for mail-in ballots to be received by election officials, resulting in tens of thousands of ballots being counted or not counted come election day? Yawn.

Last week, our reporter Audrey did a fabulous job giving us a current lay of the litigation land right now:

The GOP is currently litigating in 19 states over election laws that institute universal mail-in voting, no-excuse absentee ballots, and/or other election laws that Republicans believe jeopardize the integrity of our democratic system. The Republican National Committee recently doubled its legal budget to $20 million—after an initial commitment of $10 million in February—to challenge statewide election laws.

$20 million buys a lot of worms for the diorama if you know what I mean. Unfortunately for you, dear reader, I am a lawyer and we’ll be following these cases as they progress here and on Advisory Opinions. #sorrynotsorry

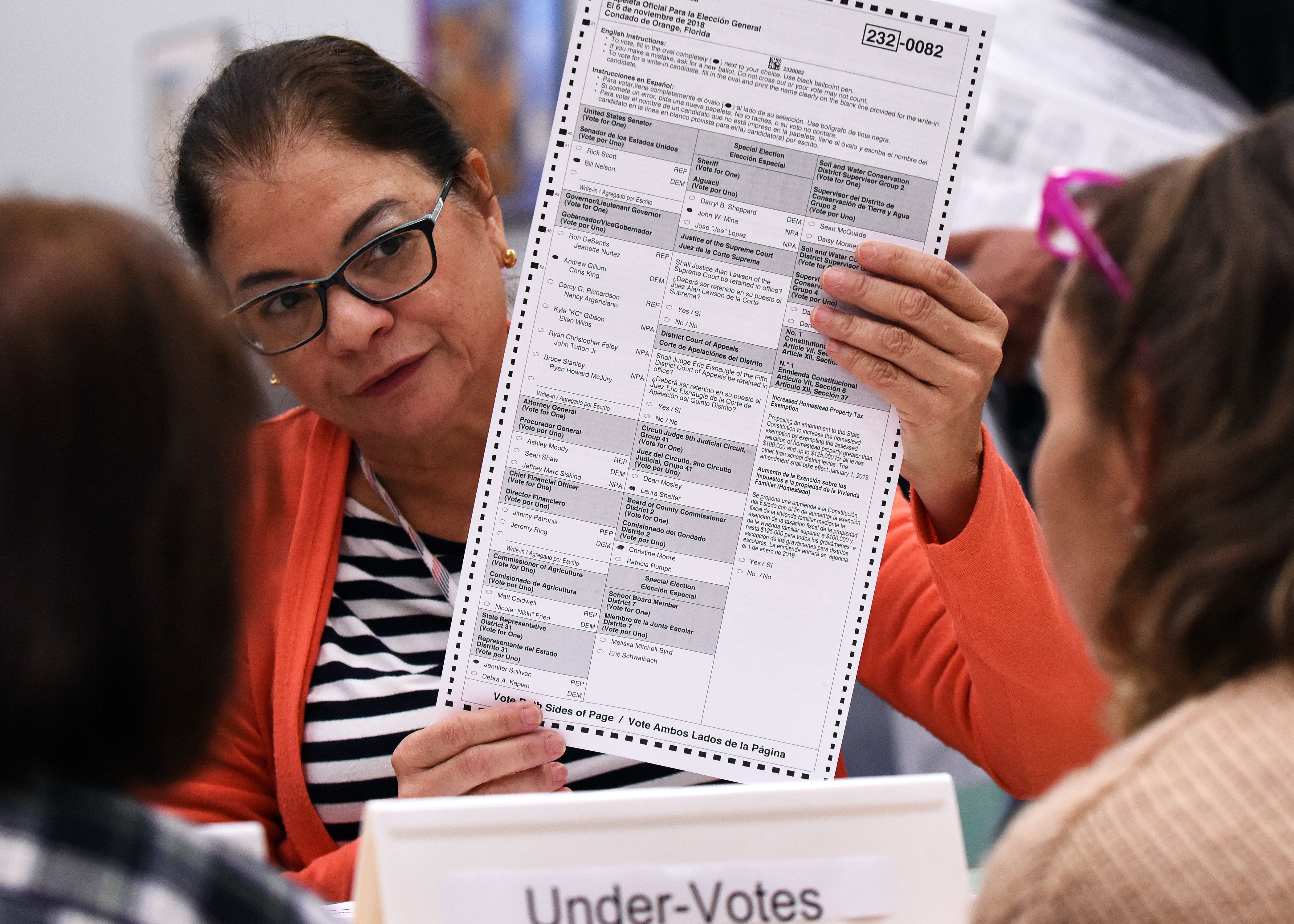

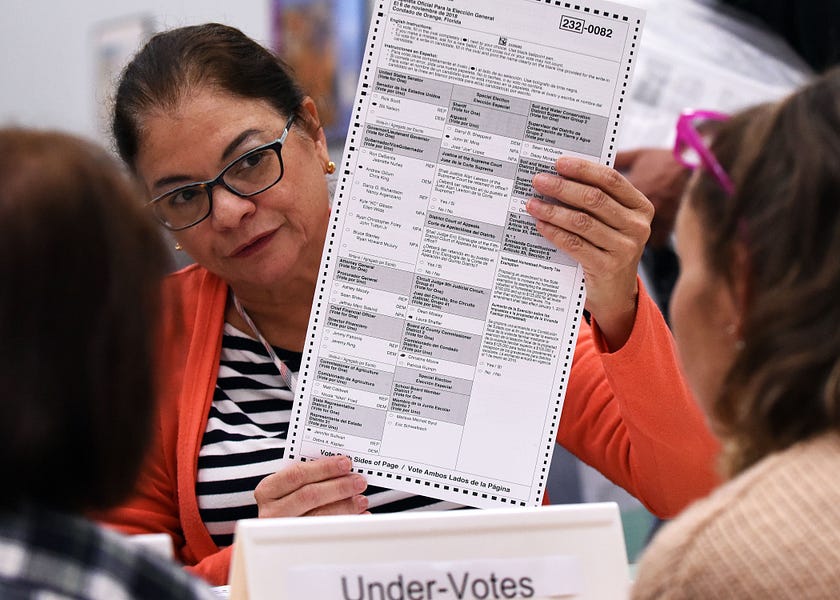

Lastly, there’s recount prep. Months of work by dozens of lawyers resulting in thousands of pages stuffed into binders, including draft motions to file in courts around the country that all comply with local jurisdictional rules and intricately footnoted descriptions (lawyers LOVE footnotes) of exactly how a ballot is to be transported to its next destination after the initial count. And then Election Day is all wrapped up by 9 p.m. and none of those binders ever even gets opened. Well, for a recount lawyer, it can feel a lot like epididymal hypertension.

There is one exception. On rare occasions, there is a recount-style event before Election Day. In Palm Beach County in 2012, 60,000 absentee ballots went out with a typo that meant the vote tabulating machine couldn’t read them. As a result, “volunteer workers [had] to copy the votes by hand onto new ballots to ensure they [were] counted by the county’s tabulation machines.” And if you’re wondering how Palm Beach County could possibly be so careless after being widely mocked in 2000, I would invite you to Google a little bit about the just-recently-former Palm Beach County elections supervisor, known for her “combative incompetence.”

In the end, close to 30,000 ballots with a dozen-plus votes per ballot were transcribed onto fresh ballots by pairs of volunteers and monitors in an industrial warehouse near a Wendy’s off I-95 day in and day out in October. And each of those tables had a lawyer from each presidential campaign keeping a watchful eye to ensure that not one vote was lost. I headed up the Romney team and a section-mate of mine from law school headed up the Obama team. It felt like a skirmish that presaged the big battles to come after Election Day. But as we know now, it didn’t make a damn bit of difference.

And with that, pour one out for the band geeks in your life. Every industry has them. And at least in my former world, they’re burning the midnight oil these days even when nobody notices the lights are on.

Primary Coloring Books

Andrew’s back this week with a look over the most recent batch of Senate primaries. Even if you don’t care about Senate races as a general matter, late primaries can tell a national campaign a lot about who is turning out this cycle and which state parties have their act together. Take it away, Andrew …

The cast of characters for this year’s Senate GOP races is nearly set. Two of the three states with retiring Republican incumbents held their primaries last week: Kansas on Tuesday, Tennessee on Thursday.

Neither outcome was a particular surprise: In both races, a more straitlaced “establishment” pick triumphed over a loose-cannon challenger of the sort typically described as “grassroots.” But each outcome had interesting things to show about the mood of the party going into a tough cycle this year.

In Kansas, a GOP Senate stronghold for nearly a century but where the race is expected to be uncharacteristically competitive this November, the primary was a quintessential example of the Mitch McConnell playbook. After Secretary of State Mike Pompeo decided not to return to his home state to challenge for the seat, party leadership with left with a possible disaster on their hands in the form of the apparent next man up: Kris Kobach, the state’s incendiary former secretary of state, who marries Stephen Miller’s zealotry on immigration with Donald Trump’s love for controversy and smashmouth rhetoric.

Kobach’s two most recent resume items were running President Trump’s voter fraud commission into the ground in 2017 and getting historically crushed by Democrat Laura Kelly in the Kansas governor’s election in 2018. His weakness in a statewide election this year was a point of bipartisan national agreement.

In a redux of the 2012 Missouri Senate race between Todd Akin and Claire McCaskill, Democrats spent heavily to boost his candidacy throughout the primary season, running ads insisting that NeverTrumpers and other RINOs hated Kobach for being “too conservative.” Meanwhile, McConnell and other party leaders went to great lengths to hamstring his campaign, going after him with aggressive attack ads and convincing much of the rest of the field to unite behind a more acceptable candidate. That candidate was Rep. Roger Marshall, a two-term Trump-embracing conservative of the more ordinary mold.

One person who remained notably absent from the race was Trump himself, who was reportedly talked out of endorsing Marshall when Ted Cruz reminded him Marshall had supported John Kasich for president in 2016.

In the end, it wasn’t close. Marshall coasted to a win with 40 percent of the vote compared to Kobach’s 26 percent. A third candidate, Bob Hamilton, captured another 19 percent.

The case of Tennessee is somewhat different. Unlike Kansas this cycle, nobody really expects Democrats to mount a substantial challenge to the seat, which means the state’s Republican primary voters had carte blanche to determine what sort of Republican they wanted representing them come next year.

On Thursday, they chose Bill Hagerty, a former private-equity man who served as President Trump’s ambassador to Japan until he launched his Senate campaign last year.

With his business background, his strong connections with and endorsement from the president, and his huge name recognition advantage around the state going into primary season, Hagerty should’ve been a shoo-in. But although he pulled out the victory in the end, Hagerty had to stave off a late surge from an outsider insurgent: orthopedic surgeon Manny Sethi. In the end, Hagerty captured just north of 50 percent of the vote, compared with Sethi’s 39.4 percent.

Running a Republican grassroots campaign can be difficult in the Trump era. The president’s perpetual energize-the-base strategy has helped him to maintain unparalleled support among Republican primary voters; as a result, a presidential endorsement can be a godsend for a candidate with a challenger trying to outflank them to the right.

But Sethi gave Hagerty a run for his money anyway with a strategy laser-targeted on the culture-war fights of the day. While Hagerty ran a strategically conservative campaign that focused overwhelmingly on his relationship with the president and his support for the MAGA agenda, Sethi constantly focused on the actual issues riling up the base at the time, from repeated attacks on the Black Lives Matter movement to gadfly attacks on the U.S. pandemic response. In the days leading up to the primary, Sethi repeatedly touted the benefits of the controversial drug hydroxychloroquine and called for President Trump to fire his top pandemic expert, Dr. Anthony Fauci.

To defend himself against these attacks, Hagerty was forced into the bizarre position of criticizing Fauci as well, but then attacking Sethi for not trusting Trump’s judgment about keeping him on. “I don’t believe Dr. Fauci has done a good job advising our president,” he said in a statement days before the primary. “President Trump is quite capable of managing the executive branch, and I don’t view it as my job as a U.S. Senate candidate to tell him how to manage his staff.”

In the end, Hagerty won. But it’s remarkable how far an underdog challenger can get in a Republican primary these days just by channeling a message that feels Trumpian—even when Trump himself has definitively endorsed his opponent.

Photograph by Paul Hennessy/NurPhoto/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.