And Then There Was Arizona: Ohio, North Carolina, Missouri, and Pennsylvania all have open Senate seats up for grabs, seats currently held by Republicans who are not seeking reelection. Wisconsin and Iowa will have GOP incumbents running again in their Senate contests. Republicans have to hold onto all of those seats and win one more to take control of the body. Herschel Walker is running in Georgia against incumbent Raphael Warnock. Former Nevada Attorney General Adam Laxalt has Trump’s endorsement in Nevada against Democratic incumbent Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto. New Hampshire’s Gov. Chris Sununu and Maryland’s Gov. Larry Hogan declined to run, making both those seats harder to win.

That leaves Arizona. Gov. Doug Ducey, who has won three statewide elections, would be the favorite if he jumped in—in the primary and the general—despite or because of his pushback against Donald Trump’s stolen election claims. Unlike in New Hampshire and Maryland, Arizona will stay a top-tier race even if Ducey bows out. But look for an announcement one way or another soon. If he joins the Sununu/Hogan bandwagon, it may just answer the question,”‘Why would anyone want to be in the U.S. Senate these days?”

Oregon Shocker: As I’ve discussed on Advisory Opinions (the flagship podcast) a few times, it’s hard to disqualify a candidate from being on the ballot.

All those fantasies from both the right and the left about getting Madison Cawthorn kicked off on the grounds that his support of the January 6 rally violates the 14th Amendment’s insurrection clause? Umm, yeah, good luck with that. Why am I so certain Cawthorn will be on the ballot (and Trump for that matter)? There are lots of technical reasons. For example, the 14th Amendment says that an insurrectionist who has previously sworn an oath to uphold the Constitution as a member of Congress can’t be a congressman. But it also says that “Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability,” implying that the person still gets to be elected to Congress but the House can refuse to seat them, as happened once before actually.

(For Trump, it gets even more squirrely because technically it bars an “officer of the United States” from being “a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any state.” But president isn’t on the specified list of offices, and as the chief justice wrote in 2010, “The people do not vote for the ‘Officers of the United States.’ … ‘[O]fficers of the United States’ are appointed exclusively pursuant to Article II, Section 2 procedures. It follows that the President, who is an elected official, is not an ‘officer of the United States.’” Fun!)

But the real reason I’m so confident that Cawthorn wins is that our system has its thumb on the scale to let voters decide. Our courts don’t like to bar people from voting for their preferred candidate, based on something called the Anderson-Burdick framework. As our friends over at SCOTUSblog describe it, the Anderson-Burdick “balancing test requires courts to weigh burdens that a state imposes on electoral participation against the state’s asserted benefits.” In Anderson, the court struck down an Ohio law that required independent candidates to file by March before a November general election, arguing that the deadline was excessively early. In Burdick, the court upheld Hawaii’s prohibition against write-in voting. So the question for every other law is where it falls in that spectrum.

That brings us to Oregon where the “state’s high court upheld a determination from Oregon’s Democratic Secretary of State Shemia Fagan’s office, which found that [former New York Times columnist Nicholas] Kristof did not meet the three-year residency requirement for seeking the governorship.” Womp womp.

I’ll admit I was surprised. As the court said, “although the Court recognized that there was evidence that pointed in the other direction, the Court could not conclude that the secretary was compelled to find that [Kristof] remained domiciled in Oregon.” So in this case, the court deferred to the secretary of state to keep him off, and that means Kristof—despite raising a lot more money than any other candidate—won’t be the next governor.

Republicans almost certainly aren’t going to swoop in and win this one. But it does leave the intriguing possibility that “former state Sen. Betsy Johnson, who served for years in the state legislature as a Democrat but is now running for the governorship as an unaffiliated candidate” could take advantage of the anti-Democratic political climate for an upset victory in a crowded race of low-name ID candidates. It helps that her campaign recently got a $250,000 nudge from Nike co-founder Phil Knight too.

The Great Sort, continued: According to the Associated Press, “Barack Obama won 875 counties nationwide in his overwhelming 2008 victory. Twelve years later, Biden won only 527. The vast majority of those losses—260 of the 348 counties—took place in rural counties.”

Dave McCormick’s Super Bowl Ad: Political campaigns are most effective when they are able to run attention-grabbing ads for the least amount of money possible. Cue Pennsylvania U.S. Senate candidate Dave McCormick, who made headlines last week for running a Super Bowl ad featuring a “Let’s Go Brandon” chant—a slogan that’s code for “F— Joe Biden” among conservatives. “Left unmentioned (and probably unleaked by the McCormick campaign) was that it ran in just a single market, Pittsburgh, with only $70,000 behind it,” wrote Jonathan Tamari in the Philadelphia Inquirer last week. “For comparison’s sake, you need $1 million to make a real statewide dent on TV. It’s a common strategy, especially around the Super Bowl: do something splashy that gets free attention rather than spending your own money. It worked for McCormick, winning headlines in conservative outlets where the ad is likely to be a hit.”

Worth Your Time: The leading candidate in Ohio’s Republican Senate primary is Josh Mandel. I knew Josh before he ran for Senate in 2012. We ran in similar circles and had the same friends. (Ditto Josh Hawley, by the way.) I even spoke at one of his fundraisers in Cincinnati when I was working for the Romney campaign back then. So I’ve watched the evolution of the Mandel race with as much confusion and curiosity as anyone. And for everything I’ve read about it, I guess this piece by Politico’s Michael Kruse comes about as close as anyone has come to explaining it:

He doesn’t act the way he used to act, and he doesn’t talk the way he used to talk, say so many Democrats and Republicans alike. And they’re right. He used to present as more moderate, used to preach bipartisanship and diversity and civility, and no longer does. Perhaps most importantly, he once was conspicuously unsupportive of Trump, and now he has publicly pivoted to full-fledged MAGA. Who, they wonder, is he really? In the end, though, that elemental, sometimes poignant question that has coursed through so many of my conversations about Mandel is actually a question about the identity of the Republican Party writ large. He was, after all, considered for so long such a formidable and promising prospect — a Marine, a combat veteran, the grandson of a Holocaust survivor and a World War II soldier, a proven, prodigious fundraiser and a Republican who earned the votes of Democrats in the suburbs in a place where that was what was needed to win. Mandel, they all thought, was a big part of the future of the GOP. And they might still be right. The future’s just not what they thought it would be.

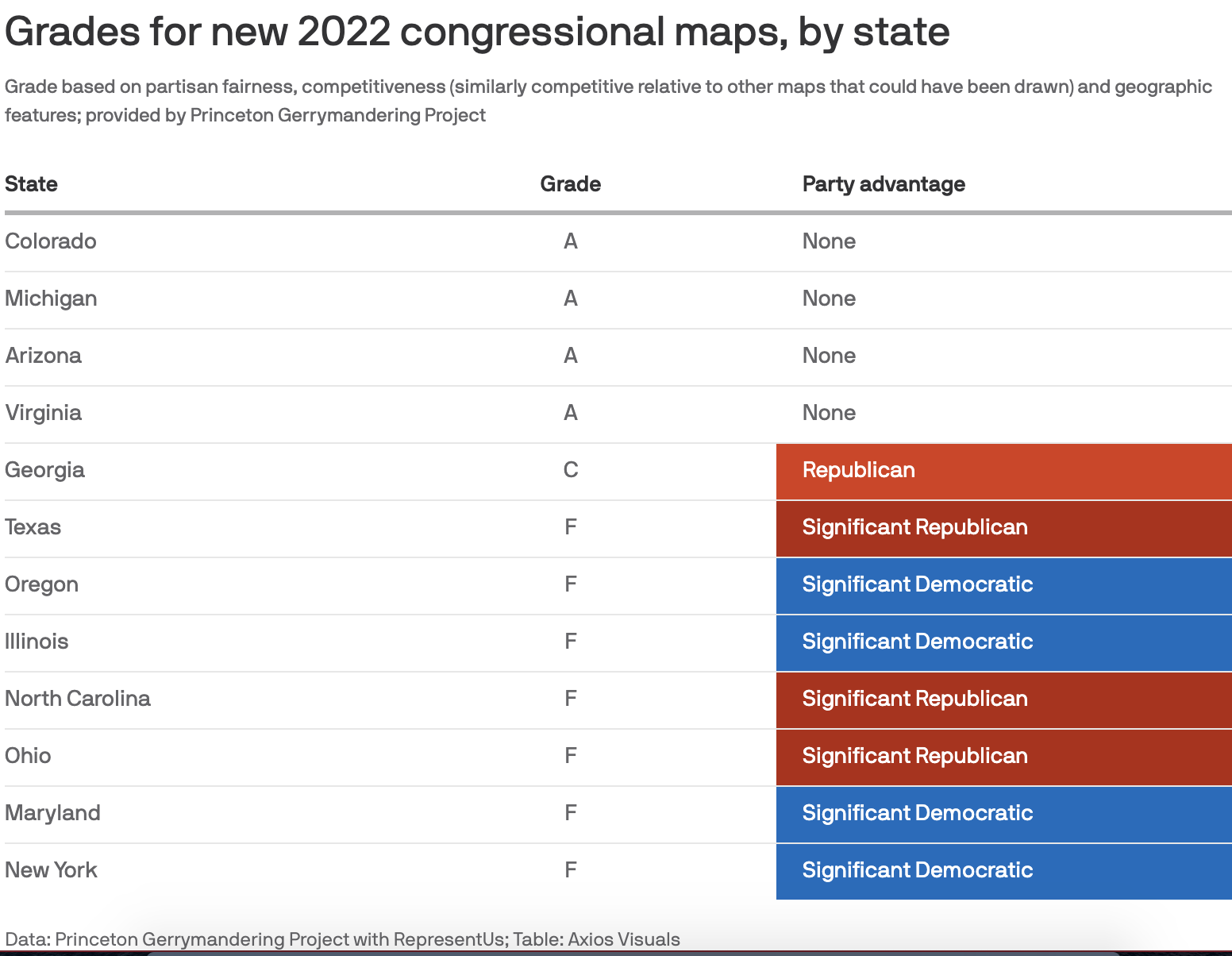

Grading Redistricting So Far: The Princeton Gerrymandering Project and RepresentUs decided to grade more than a dozen states on their post-census congressional maps and the results aren’t great. Of the four states that got As, “three of those states had maps drawn by an independent commission, as opposed to partisan lawmakers … the fourth, Virginia, had a final map drawn by its state Supreme Court, after the state’s new independent commission missed its deadline for approving a map.”

How Fundraising Tactics Pick Candidates

Last week, toward the end of the Dispatch Podcast (starting at the 52-minute mark), Steve and I got into a debate about whether Liz Cheney’s stance against Trump led to or created the space for the current pushback against Trump that we’ve seen lately from folks like former Vice President Mike Pence and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell. But the whole conversation assumed that Trump’s sway over the party is, in fact, weakening. Let me make the opposite case here.

In short, if you look under the hood at how federal campaigns actually raise money, then Donald Trump is more powerful than he’s ever been. So powerful, in fact, that it’s hard for me to even fathom how a candidate not aligned with Trump—and by aligned I mean lockstep with his campaign operatives and committees—can get through any GOP primary, let alone a general election.

The latest from Lachlan Markay and Jonathan Swan at Axios is about the overwhelming fundraising presence of Donald Trump: “22 cents of every dollar in donations processed through GOP payment processor WinRed last year went not to GOP midterm candidates but to two Trump committees: Save America and the Trump Make America Great Again Committee,” they write.

When I read that, I had to put down my phone because my mind was racing about exactly what that means for GOP candidates and would-be candidates. Right off the bat, the GOP is paying a Trump tax of more than 20 percent. And Trump decides where that money goes and which candidates—if any—he will support with that money. So far, it’s worth noting, he’s paid more in rent to himself at Trump Tower ($375,000) than he has given to candidates ($350,000).

(It’s actually a genius money laundering scheme. Trump throws lavish parties on his own properties to raise money for his federal PACs and uses that PAC money to pay himself for the venue rental fees, food, and costs. Suddenly, what started as “hard dollars” that could only be used for campaign-related expenses and to support GOP candidates is now in Trump’s bank account.)

But that’s not even the half of it. If the fundraising game has shifted to the small dollar/online donors (which, again, are only about 2 percent of voters) and that sliver of donors is getting targeted—as Axios reports—14 times a day just by Trump, how do any other candidates break through for their own campaigns?

Swan and Markay summarized the problem nicely, I thought:

• Donor burnout, and diminishing returns from a flood of frantic emails and texts — not just from Trump, but also other candidates invoking his name. There’s also a scenario in which Trump squats on hundreds of millions of dollars, rather than spending it on other Republicans.

• The “quadrupling-down” approach that’s proved effective for Trump may actually make it harder — and more expensive — for other Republicans to raise money online.

• Trump’s approach is spurring other campaigns to lean heavily on his brand in their own fundraising appeals. That keeps Trump essential not just to the Republican political brand but to its ability to raise money online.

And all of this highlights the nitty-gritty of the digital fundraising world. Hitting your list too often means that recipients burn out and unsubscribe. That’s why fundraising teams are constantly “renting” each other’s lists—asking a similarly aligned group to send out their fundraising pitch to that group’s email list. In return, the group can ask for a flat rental fee, but more often they get a cut of the fundraising haul. The result is a cycle in which the only people left on any of these GOP lists are the most hardcore Trump fans who haven’t unsubscribed after being hit more than a dozen times in a day by Trump.That makes list rentals more expensive overall, and it means that sending “Trump copy” is more valuable to the list owner. So if you’re a candidate who believes in limited government and doesn’t mention Trump in your fundraising appeal, you’re going to have a very hard time finding anyone who will send out your copy to their list.

It may be pissing off people like McConnell or other party elders but there’s nothing they can do about it. If you think about it that way, McConnell taking shots at Trump is like shooting a gun up into the sky to complain about gravity. The laws of gravity didn’t get any weaker.

And think about the effect that lopsided fundraising advantage has on who succeeds in a GOP primary: Who runs in the first place if you’re told all your fundraising appeals will have to mention Trump? Who gets out ahead in 2024—even if Trump doesn’t run? Or if Trump does run, will other 2024 GOP presidential candidates be able to find another fundraising mechanism to compete?

When I was on the Carly Fiorina campaign, we knew we wouldn’t be able to compete with the fundraising operations of, say, a Ted Cruz—a sitting senator with years to build up his list. The answer was to shift everything we could to the super PAC, which was named Conservative, Authentic, Responsive Leadership for You and for America … aka CARLY for America. (The campaign was called Carly for President—totally different, as you can see.) We, on the campaign side that was regulated by federal financing laws, would post our schedule on a publicly available Google calendar. The super PAC would then do all the heavy lifting—getting would-be primary voters to attend, set up the venue, sign up volunteers.

As one reporter noted at the time, “Mrs. Fiorina traveled with a few campaign aides who squeezed into a white sport utility vehicle, while a team of at least seven people from the super PAC swooped in, often hours ahead, at each stop to stage her backdrops, set up sign-up tables and arrange stacks of posters and placards.”

And we weren’t the only ones. Ben Carson, Mike Huckabee, Rand Paul, and Bobby Jindal all did something similar—although I’d argue that we took it further than any of them did. And why? Because none of those campaigns thought they could compete on the fundraising side.

But that was 2015 when the problem was too many hungry, hungry hippos gobbling up all those marbles in the middle. In 2023, the problem will be that there’s only one hippo and he has the size and temperament of a T. Rex.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.