Campaign Quick Hits

TV as Reality: 51 percent of all Americans believe that The West Wing more than any other TV show about politics is realistic, beating out shows like Scandal, The Good Wife, and 24. Concerningly, 42 percent thought House of Cards was realistic. But then again, only 27 percent of Americans thought that Veep was realistic.

For what it’s worth, as someone who has worked in all three branches of government and on three presidential campaigns, Americans are right: The West Wing overall is the most realistic … though I’d put Veep in a close second. Very, very close.

Polling as a Predictor: Wondering how accurate a poll can possibly be this far out from November? Not very. FiveThirtyEight did the math:

Senate polls conducted during the first six months of an election year had a weighted average error of 8.2 percentage points — meaning the average polling margin between the Democratic candidate and Republican candidate was 8.2 points off the actual margin. Gubernatorial polls conducted during this span had a similar weighted average error of 8.6 points. That’s not super precise, but it’s also not much worse than polls conducted in the final three weeks of the 1998-2020 campaigns, which had a weighted average error of 5.4 points.

On the one hand, polls at this point aren’t likely to be much worse than polls in October. But on the other hand, polls in October aren’t that great.

What’s In a Wave

From Amy Walter over at Cook Political Report:

The [National Republican Congressional Committee] added another 10 House districts to its already robust list of 72 Democratic-held targets. And on the Democratic side, the House Majority PAC announced it would be reserving nearly $102 million in advertising in a whopping 51 media markets for the fall campaign. These moves suggest that both sides see the possibility of a Red Tsunami in 2022.

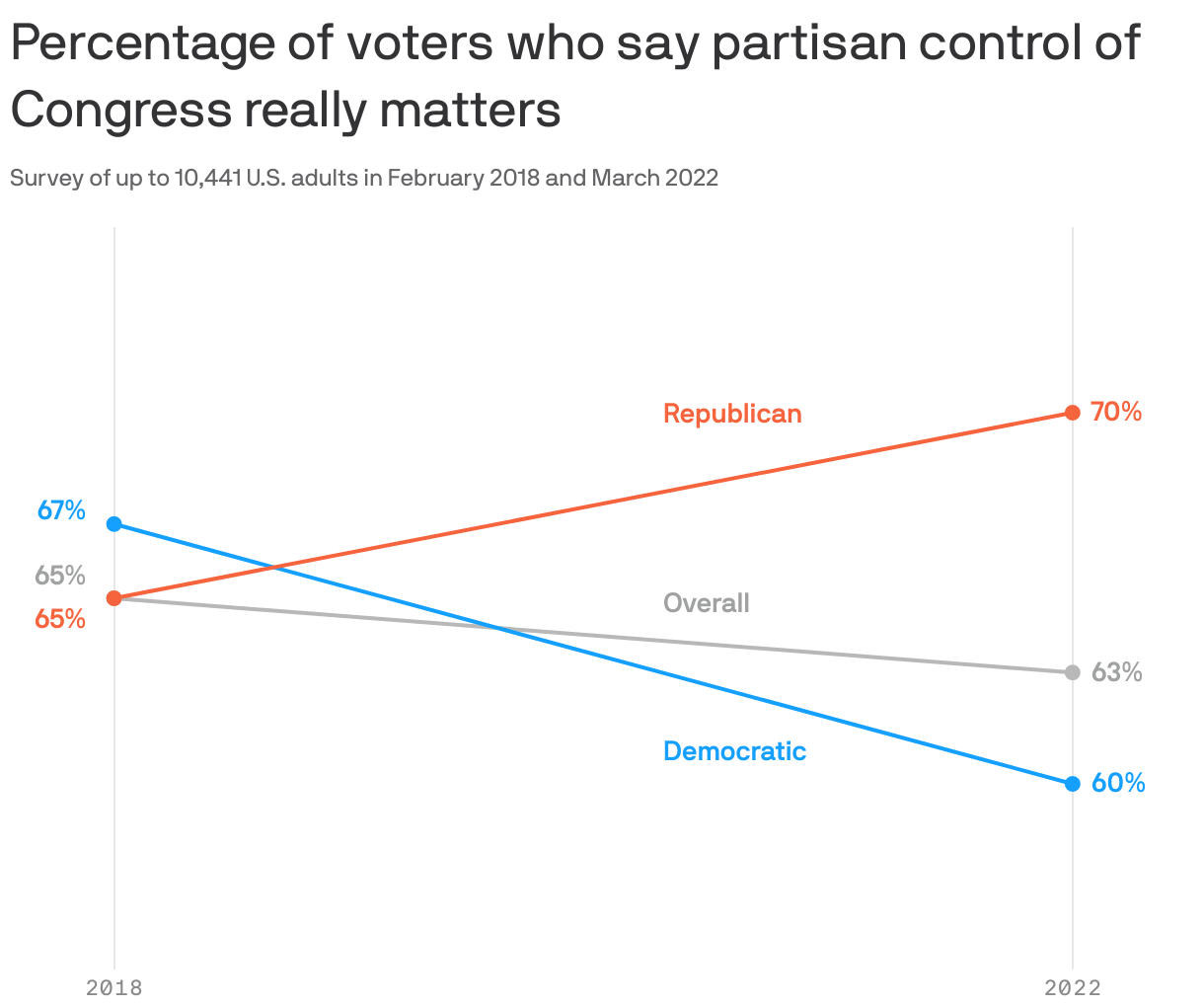

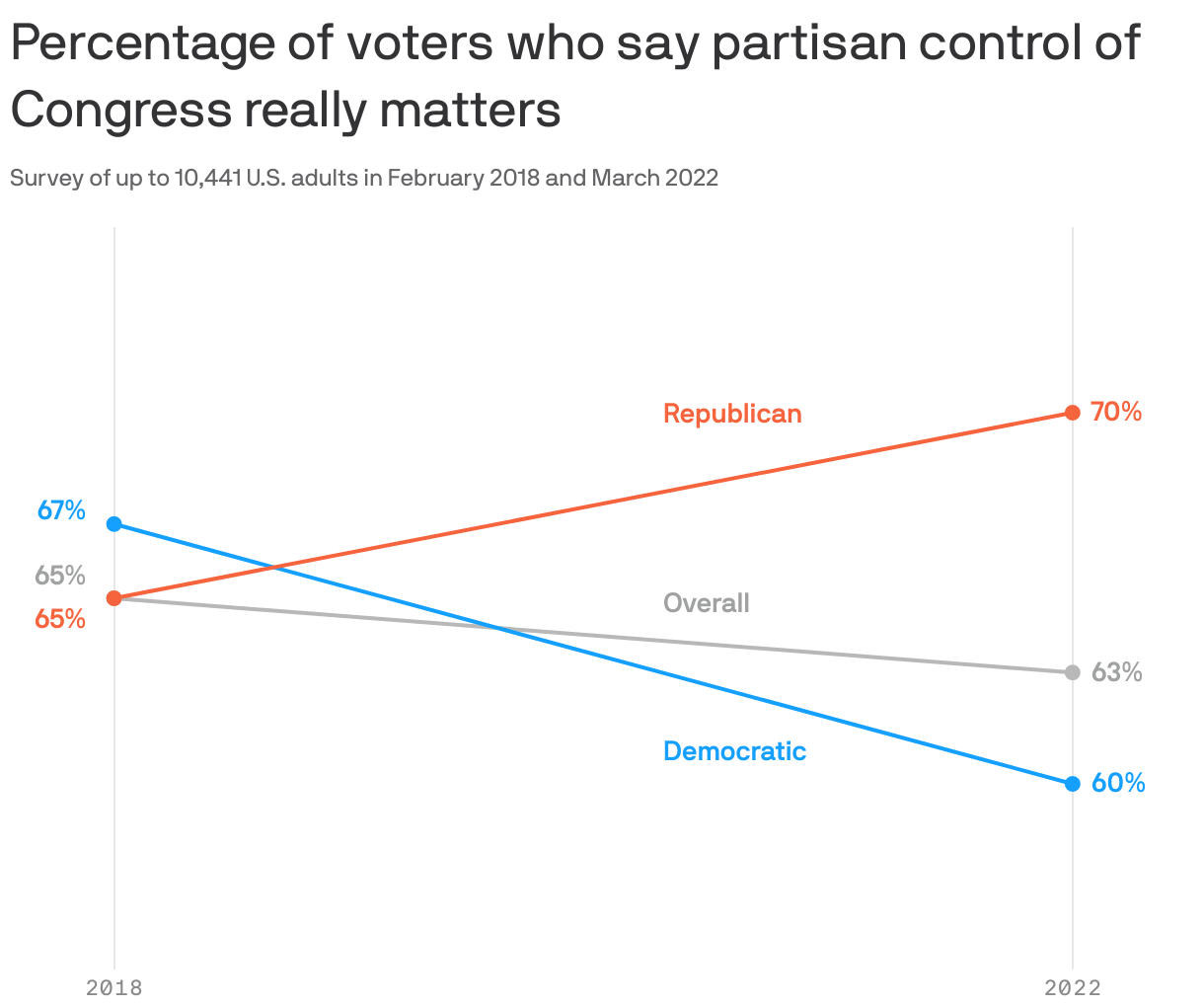

Eighty-two targets. Wowzer. And what’s driving the GOP confidence? First, there’s President Biden’s insanely low and dropping approval numbers. According to Gallup, only Donald Trump had lower numbers at this point in his presidency and Biden is tied with Harry Truman. And then there’s every measure of enthusiasm pollsters can come up with. Here’s the latest from Pew:

But there’s a problem. As Amy goes on to point out, waves don’t quite mean what they used to when you get into the mechanics. Waves are about “flipping” seats, meaning that either the district itself is fairly evenly divided between voters of both parties or that there’s a member in an outlier district (like a Joe Manchin in West Virginia). But there are fewer and fewer of either. Parties are getting increasingly sophisticated at gerrymandering to protect incumbents so there are fewer true “swing districts.” And even fewer outliers as evidenced by the fact that only two pro-life Democrats remain in Congress (and one of them, Henry Cuellar, may well lose his primary in the runoff election next month).

So while President Biden’s poll numbers are abysmal and GOP enthusiasm is high, “those metrics are bumping up against an increasingly ‘sorted’ House with few marginal seats and few incumbents sitting in the ‘wrong district,’ according to Amy. As a result, she says even a huge wave may translate to only 15 to 25 seats.

And looking at the state legislative races highlights this problem even more.

According to the director of CNalysis, a nonpartisan state legislative election analysis firm, “Republicans are favored to win 244 (!) districts that voted for Joe Biden in 2020.” Surely another sign of a big wave.

But what would that actually translate to in terms of flipped seats? Right now, Republicans control 3,980 seats or 54 percent of state legislative seats. And according to CNalysis, Republicans are favored to gain a net 161 seats (meaning they already control some of those Biden districts and Democrats will flip some too). That’s a 3 percent increase.

As Charlie Cook, of Cook Political Report put it:

Biologists often talk about the need for biodiversity. In politics, it’s healthy to have parties with internal diversity, not only along lines of gender and race but geographical and ideological diversity, as well. Just as inbreeding can distort certain characteristics in nature, in politics it has an effect too, creating a certain tone-deafness or an inability to see how anyone else might see an issue differently.

So true. And when you see headlines about a wave election, bear in mind that when biodiversity is as low as it is now, even waves aren’t what they used to be.

House GOP Touts Female Candidates

NRCC Chairman Tom Emmer told reporters last week that House Republicans are “breaking records” with regard to the number of women and candidates from minority communities who are launching bids for Congress. “At this time in the last cycle, we had 227 women that were filed—today, it’s approaching 300,” he said. “We’ve got the highest number of Hispanic candidates that have ever run for office as Republicans for the U.S. House.”

The problem for Republicans has rarely been the diversity of potential candidates, but how few of them make it through the primaries. Traditionally, Republican women have been far less likely to win a primary than their Democratic counterparts—though equally likely to win the general election if they can get there.

In 2018, for example, Republicans elected 22 new members, only one of whom was a woman. But in 2020, Republicans elected 46 new members and 19 of them were women. Interestingly, in that same cycle, Republicans lost three open seats that had previously been held by Republicans. All three went to Democratic women who ran against Republican men. And in two of the three, the Republican man had beaten a woman as the runner-up in the primary and in the third race, the GOP canceled the primary to nominate a man for the seat.

As Rutgers professor Shauna Shames told FiveThirtyEight, “The research I’ve done suggests that the primary campaign is the toughest hurdle for Republican women to get through, and many do not run, knowing they will not make it through the primary — where voters tend to be far more conservative than the Republican Party at large.”

And why are primaries harder for GOP women? There’s no one answer. Sure, Democrats have an institutional head start in some respects. The most obvious example is EMILY’s List, which specifically backs pro-choice female candidates in Democratic primaries and helps them with fundraising. But as someone who has spent a lot of time studying this issue, it’s possible that women had trouble raising money once upon a time but it isn’t an issue now and it hasn’t been for a while.

It’s also easy to say that the Democratic Party has prioritized “identity politics” while attempts to specifically tout a candidate’s diversity has been seen as a negative on the Republican side. But the reality isn’t quite so neat. Republicans have been specifically trying to recruit “diverse” candidates as far back as I can remember. When I was at the RNC a decade ago, we even had a program to specifically highlight GOP candidates who were young, female, or people of color with donors and reporters.

The real problem is more structural. Congressional primary voters tend to want candidates at the ideological extreme of their parties. Women of both parties tend to have more liberal voting records than the men in their parties at the state legislative level, where a lot of congressional candidates come from. This means that a Democratic woman’s more liberal voting record is more likely to appeal to Democratic voters. Whereas it’s just the opposite for the GOP women, where more moderate female candidates are less likely to win a GOP primary.

There’s also the problem that voters believe that female candidates are more liberal than male candidates even when a specific female candidate may be more conservative than her male opponent. Democratic women benefit from this stereotype; Republican women are hurt by it, contributing to the problem you can see in the chart below: The more conservative a congressional district on either side of the aisle, the less likely it is to elect a woman.

Trump Endorses Sarah Palin

Former President Donald Trump gave his “Complete and Total Endorsement” to former vice presidential candidate and former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin on Sunday, just two days after she announced her run for Alaska’s sole congressional seat. The seat was most recently held by GOP Rep. Don Young, who died last month after holding the seat for 49 years.

It’s not clear how the primary will shape up or whether this will be another test for the value of a Trump endorsement—after all Sarah Palin has the highest name ID of any person in the state (and probably the highest national name ID of anyone running for Congress except for Nancy Pelosi … and maybe even including her). The special election open primary will be held on June 11, and then the top four candidates will proceed to a ranked-choice runoff on August 16.

Curious who else is running? Chris Stirewalt covered the race in more depth over on the website:

The field to replace Young includes state Sen. Josh Revak, a combat-injured Iraq veteran who worked in Young’s office for six years before running for the state House and eventually getting appointed to the state Senate. He seems to have to have the backing of Young’s crew and a good rapport with Republican Gov. Mike Dunleavy. The Murkowski faction is represented in the field by Tara Sweeney, a Cabinet secretary under Frank Murkowski who served as assistant secretary of the interior for Indian affairs during the Trump administration. Nick Begich III, the grandson of the congressman whom Young was elected to replace in a special election 49 years ago, is running, too. Begich got in the race for the full term starting in 2023 before Young’s death but is now also in the hunt for the unexpired term.

The real full-circle candidate, though, is Emil Notti, the Democrat whom Young narrowly defeated to win his first term in 1973. The 89-year-old Native leader told the Anchorage Daily News “I’m not looking at a long-term career, so it wasn’t really a hard decision.”

Andrew can’t get enough of Georgia these days. Here’s some more of his thoughts on Peach State politics.

Kemp Goes on the Offensive

The gloves are coming off in Georgia’s Republican governor’s primary. Until recently, incumbent Gov. Brian Kemp had largely ignored the insurgent Trump-backed challenge of former Sen. David Perdue—not because Perdue wasn’t a significant opponent, but because his team judged his best path to reelection was to focus on his own record and the threat of Democratic challenger Stacey Abrams. But that changed last week following comments Perdue made on a far-right show called BKP Politics over Kemp’s support of raises for teachers and a two-month suspension of the state gas tax.

“It’s disgusting to me as a private citizen,” Perdue said, “to see a governor throwing our taxpayer money around in an election year as giveaways, to teachers in terms of pay raises, to taxpayers in terms of a one-time deal, in terms of a gas tax reduction—watch this, for only two months.”

Perdue’s point was to accuse Kemp of enacting popular actions right before the election to help his own primary chances. Of course, the thing about popular actions is that they’re popular—so it wasn’t surprising that team Kemp pounced on the comments. “In his own words, David Perdue called teacher pay raises & suspending the gas tax ‘disgusting,’ reads the grainy-footage attack ad. “David Perdue: against teachers & taxpayers.” (Perdue punched back at the ad as a “false attack from a governor who is desperate to keep his job” and “trying to play election-year politics.”)

Perdue’s teacher-raises hit was unquestionably unfair—Kemp has supported increasing teacher pay since the beginning of his term—while the gas-tax critique was a grayer area. It’s true that the two-month suspension of the state tax lasts until just after the primary, although a spokesperson for Kemp told The Dispatch that there will be an “opportunity to evaluate any further needs” after that. One might argue that handing out election-year goodies here and there is the incumbent’s prerogative that corresponds with the challenger’s ability to make shoot-for-the-moon campaign promises, like Perdue’s pledge to abolish the state income tax altogether.

Regardless, what’s interesting is that this is the grounds on which Kemp was finally willing to hit Perdue—who has been going after Kemp for not “supporting” Trump’s effort to fudge the 2020 election results in Georgia for months. In campaign events around the Atlanta area last week, Perdue was flanked by former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, who told attendees that “Brian Kemp cost us control of the U.S. Senate, and Brian Kemp took 16 electoral votes away from Donald Trump.”

It isn’t as though Kemp couldn’t lean into the elections issue if he thought it was a good strategy—he signed an election-reform bill last year that waslauded by conservative groups and multiple audits of the 2020 election found no malfeasance. Instead, he’s just hoping that the subset of the electorate that remains bought in on Trump’s stolen-election narrative isn’t a big enough coalition to swing the race in Perdue’s favor. If he’s right—and he’s led Perdue all along in fundraising and in the polls—it will mark a major sea change in how we view Trump’s hold on the Republican Party. All along, Trump has presented Republican politicians with a choice: with me or against me, MAGA or Never Trump. Right now, Kemp’s just refusing to play that game.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.