Good morning. Next week is set to be a quieter one on the Hill—Congress isn’t scheduled to return for votes until the week of May 10. The last time members had a recess, we brought you an off-the-daily-news-cycle issue including interviews with two House freshmen about their time in Congress so far. Are there any specific lawmakers you want to hear from next week? We’ll try our best to make it happen. Let us know in the comments.

Lawmakers Push Staff Pay Bump

Top Democrats, concerned about turnover and institutional brain drain, are calling for a boost in funding to pay congressional staff higher salaries.

In a letter to leading House appropriators this week, House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer and Democratic Caucus Chairman Hakeem Jeffries urged a 20 percent increase in funding for members’ spending allowances. They noted that staff salaries over the past decade have not accounted for inflation, and working for Congress is, for many, unsustainable.

Hoyer and Jeffries wrote that a funding increase for individual offices, committees, and leadership offices would not only enable existing congressional staff to receive pay raises and more benefits, but also increase capacity to recruit talented new staff who would otherwise be deterred by less competitive salaries.

Hill staff keep the place running, often working long days performing thankless tasks. They write legislation, schedule lawmakers’ days, organize hearings, meet with constituents and interest groups, and spend time learning the important policy details members of Congress don’t have time to delve into as thoroughly. Congressional staff work demanding schedules in a stressful environment—even those who don’t spend hours each day answering angry phone calls about a wide range of topics.

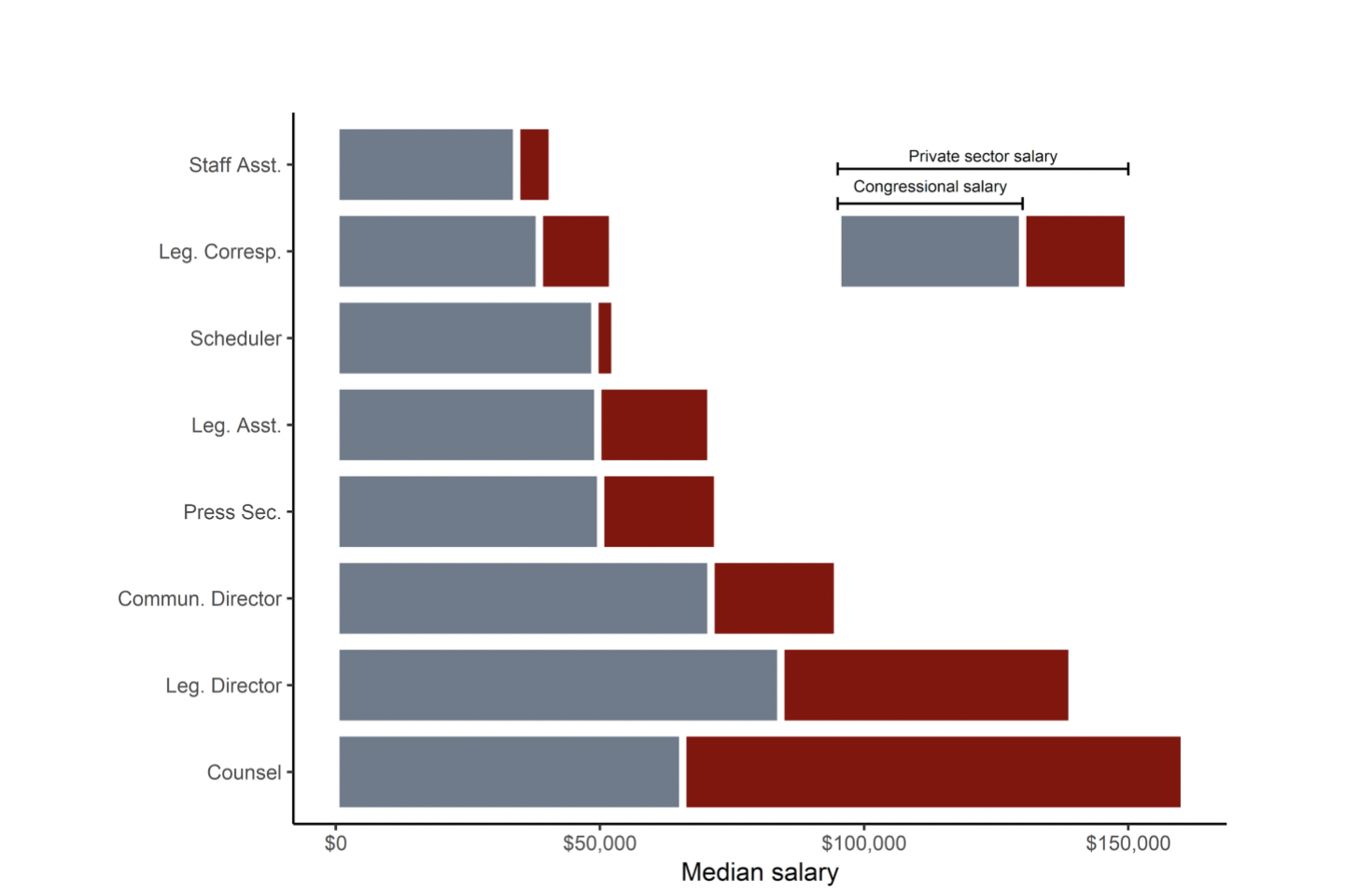

Pay on the Hill hasn’t kept pace with inflation. Most median salaries for various House positions are effectively lower than they were in 2010, with some as much as 20 percent below inflation-adjusted 2010 levels. The cost of living in Washington, D.C. is high. It’s not uncommon to find Hill staffers packed into houses or apartments with a bunch of roommates sharing the rent to make ends meet. In later years, even with more established staff making higher salaries, it can be difficult for Hill personnel to save enough money to buy a home or to feel financially secure enough to start families.

This contributes to shorter careers on the Hill and fewer experienced staff remaining on the job. According to a September report from New America, a left-leaning think tank, the average tenure for staff on Capitol Hill is 3.1 years. “About 65 percent of staffers plan to leave Congress within five years,” the authors of the paper wrote. “Even more strikingly, 43 percent plan to depart by the end of the Congress in which they are employed.”

Congressional staff know they could make more money in the private sector, especially those who have relevant policy experience in lucrative fields, like financial services or tech. Here’s a visual comparison from expert Casey Burgat—legislative affairs program director for George Washington University’s Graduate School of Political Management—in his 2019 written testimony for the House Appropriations subcommittee on the legislative branch:

Many Hill staff would like to stay in public service—but working for Congress just isn’t the most sustainable way to do so. If they don’t go to the private sector, some staffers seek to transition to the executive branch, where they can work better hours for more money.

“In our experience, House staff generally prefer working in public service and would remain on Capitol Hill longer if they no longer felt that their only option to afford the cost of living in the Washington metro area and achieve economic security in the middle class is to leave and pursue more lucrative positions in the private sector or the executive branch,” Hoyer and Jeffries wrote in their letter this week, addressed to House Appropriations Committee Chair Rosa DeLauro and Rep. Tim Ryan, who chairs the Appropriations subcommittee on the legislative branch.

Hoyer and Jeffries added that low pay also makes it more difficult to hire staff from economically underprivileged backgrounds, who can’t rely on financial support from their families.

“This often has the effect of advantaging those from high-wealth families,” they wrote. “Pre-existing wealth should not be a barrier to entry for a career as a congressional staffer.”

A 20 percent increase in members’ representational allowances could help shore up staff salaries and make Congress a more competitive employer. But it may not make enough of a difference to reverse these trends in the long run.

“It definitely won’t hurt. Twenty percent is a really big bump,” Burgat told The Dispatch Thursday. “But keeping in mind inflation, that will get us back to like 2011 baselines. So it’s really filling in the hole that is already existing.”

“The question then becomes what do they use it for? Members in their own offices, committees too, really have a ton of leeway in how they hire and what salaries they set for what positions. It’s kind of up to them,” he said. “And so does that mean they’ll hire more staff and pay them less? Will they give raises to current staff? There’s a lot of questions to be asked about how that money will actually be spent.”

Several current and former Hill staffers have said the new funding should come with requirements about how the money can be used. Without guardrails ensuring members spend the additional funding on raises for staff or hiring new employees, they fear, members could just direct it to other priorities. Lawmakers have a great deal of discretion to use their office’s funds as they see fit. It’s not particularly likely members will agree to limits on the new funding. “This is one thing where they have almost complete authority,” Burgat told The Dispatch. “So they’re reluctant to have someone else tell them how to spend it.”

Strong political forces have played a role in keeping staff pay low over the past two decades. Those considerations aren’t going away any time soon. Many members are afraid to pay staff well, worrying voters will look at that spending unfavorably. Primary challengers could hit Republicans, especially, if they were to support adopting such a substantial increase in funding for legislative branch operations this year.

“They think that it would be cast, and probably rightfully so, that they’re spending money on themselves,” Burgat said. “If you’re able to ask folks at the member level or even a voter level, ‘Should staffers be paid consummate with the private sector?’ I think you’ll get a lot of support there. But it’s mostly about the politics of members voting to increase funds available to them, particularly when Congress is as unpopular as it is.”

Burgat added that there are a great deal of misconceptions about Hill staffers among the public, but it can be helpful to point to the numbers.

“The average staffer is a 24-year-old that’s been here two years, who’s already looking to leave,” he said. “Given how much that they do and how much reliance there is on them? There’s no way that you would design a system on that premise. It’s just bad governance.”

Police Reform Talks Continue

After his primetime response to President Joe Biden’s joint address before Congress on Wednesday night, South Carolina Sen. Tim Scott got back to work in his high-profile negotiations with Democrats for a police reform bill.

Scott—alongside GOP Sen. Lindsey Graham and House Republicans Pete Stauber and Brian Fitzpatrick—met with Democratic Sens. Cory Booker, Dick Durbin, and Democratic Reps. Karen Bass and Josh Gottheimer on Thursday afternoon to discuss the legislation.

It was the largest in a series of recent meetings to try to hammer out an agreement. Scott has been holding smaller conversations with Bass and Booker in recent days.

The two parties have been at odds over how best to address police violence and justice in policing after George Floyd was killed last year. Talks for bipartisan legislation that could pass into law have ramped up this month in the wake of former Minnesota police officer Derek Chauvin’s conviction for Floyd’s murder. Lawmakers hope to carve out a solution by late May, which will mark a year after Floyd’s death.

House Democrats have twice passed a bill seeking an end to the use of chokeholds, no-knock warrants at the federal level, and qualified immunity, the legal doctrine that largely shields law enforcement officers from liability. Scott’s measure in the Senate has some similarities—it also incentivizes states and local governments to ban the use of chokeholds and would provide funding to increase the use of body cameras. Scott’s bill doesn’t include a federal ban on no-knock warrants but has provisions to gather data on their use.

(You can read a more detailed breakdown of the differences between the House Democratic bill and Senator Scott’s legislation in last Friday’s Uphill, here.)

The biggest sticking point between the two measures is qualified immunity: Republicans are opposed to removing the legal shield from civil action officers typically have in the course of their work. Scott has instead argued for language to enable legal action against police departments and local governments instead of individual officers.

It’s not clear what a potential deal will look like. The negotiating parties have kept relatively quiet about the policy details, even as they have projected optimism about progress in recent weeks.

“We just had a general discussion, and so you know we’re not going to go into the specifics,” Bass told reporters Thursday as she and Graham emerged from the meeting.

“We’re trying hard, and when you’re trying hard, you usually get to where you want to go,” Graham said.

“She’s wonderful,” he added of Bass. “I probably just ruined her political career, but she’s wonderful.” (This short C-SPAN video of members leaving the meeting captures some of the chaos of Hill reporting, if you want a look behind the curtain.)

New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker said the discussion went “really well.”

“We will definitely meet until we get this done,” he added.

And Scott said he is hopeful a deal can be struck.

“Nothing happened in the meeting that deters me from being optimistic that we can get there,” he said.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.