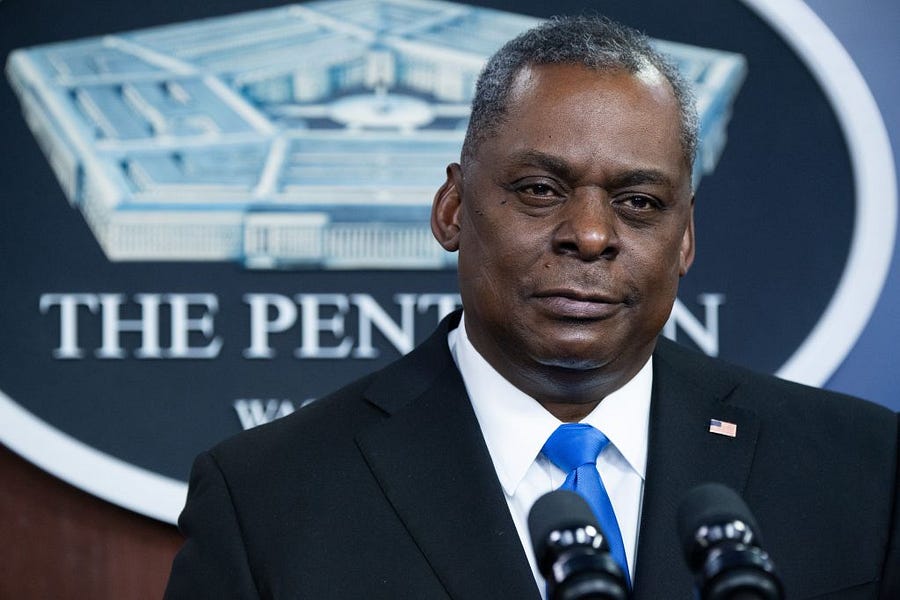

During a press briefing on February 19, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin described China as the Pentagon’s “primary pacing challenge.” Austin was speaking shortly after attending his first NATO defense ministers meeting as the Pentagon chief. He outlined the challenges NATO faces, including “a resurgent Russia, disruptive technologies, climate change, an ongoing war in Afghanistan, and the persistent threat of terrorism.” Still, it’s clear that “an increasingly aggressive China,” as Austin phrased it, was first and foremost in his mind.

This is hardly surprising. A sea change within the Defense Department occurred during the Trump years, as the Pentagon came to prioritize a return to so-called “great power competition” above all else. This agenda has continued into the first weeks of the Biden administration, with Austin vowing to work with other NATO countries to defend “the international rules-based order, which China has consistently undermined for its own interests.”

But just as the Trump administration was forced to contend with other issues—namely, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, which many in the Pentagon would rather leave behind—so, too, has the Biden team. Austin, to his credit, made it clear that he had time to deliberate the course forward in those conflicts; even though neither conflict is easy, there is little political will to remain involved in them and the Defense Department has other priorities.

On Afghanistan, Austin said the new administration is coming “to grips with the reality on the ground.” But there is a large gap between the “reality” of the war in Afghanistan, and how some in Washington prefer to see it.

The reality is that the February 29, 2020, deal between the Trump administration and the Taliban did nothing to bring about peace. It was simply a withdrawal deal, in which the Taliban agreed to (mostly) abstain from attacking American forces as they left.

As the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) confirmed in a report released Tuesday, the months that followed the inking of that deal were bloody, with the violence surging after the onset of so-called intra-Afghan “peace talks” in September. Although the total number of civilians killed or wounded throughout 2020 was thankfully less than in previous years, the last quarter saw an uptick in violence as the Taliban went on the rampage. In all, 8,820 civilian casualties (3,035 killed and 5,785 injured) were recorded in 2020. And UNAMA found that the Taliban was responsible for more civilian casualties than any other party—45 percent of the total (with 1,470 people killed and 2,490 injured in Taliban violence). The Islamic State’s regional arm and other “undetermined anti-government elements” continued to wage war as well. In sum, the jihadis killed or injured more than half of the civilians who fell victim to violence in 2020—far more than those caused by the Afghan government (22 percent of the total).

Austin is aware that the war continues to rage on, but he didn’t lay blame at the Taliban’s feet, as he should have. “Clearly, the violence is too high right now, and more progress … needs to be made in the Afghan-led negotiations, and so I urge all parties to choose the path towards peace,” Austin said. “The violence must decrease now.”

Austin’s wording was neutral—as if every party to the war were equally responsible for the continuation of the conflict. But that is clearly not true. The Afghan government has repeatedly called for a ceasefire, so real peace talks can begin. The Taliban has refused, preferring to kill and maim Afghans in the name of resurrecting its totalitarian Islamic Emirate.

Austin explained that the administration is conducting an “interagency review” of all options, but they are generally “mindful of the looming deadlines.” There is really only one deadline. The Feb. 29, 2020, withdrawal agreement between the U.S. and the Taliban stipulated that all American and NATO forces be out of Afghanistan by May 2021.

Some have recommended that the Biden administration attempt to renegotiate this withdrawal deadline with the Taliban. That was the first proposal in a report released by the congressionally established Afghanistan Study Group earlier this month. So far, however, the Taliban has refused to entertain any extension. And if the Taliban is willing to reconsider—and that’s a big if—you can bet they’ll demand more concessions. But Americans should be asking: to what end?

The Afghanistan Study Group’s report begins with an unrealistic claim: that “there is a real opportunity to align U.S. policies, actions, and messaging behind achieving a durable peace settlement to end four decades of violent conflict in Afghanistan.” It’s difficult to see how anyone could come to that conclusion. There is zero evidence that a “durable peace settlement” is currently in the cards.

Austin says the U.S. is “committed to a responsible and sustainable end to this war, while preventing Afghanistan from becoming a safe haven for terrorist groups.” But there is no reason to think the Taliban wants to “end” the war before achieving its central political goal: the resurrection of its Islamic Emirate. And no one should believe that the Taliban is going to break with or otherwise restrain al-Qaeda, absent significant evidence to that effect. These are the realities of the war.

If the Biden administration is going to operate within reality, as Austin says, then the U.S. faces a simple decision: maintain a military presence and continue to assist the Afghan government after May 1—or leave.

With respect to Iraq, Austin said he “reiterated our strong commitment to the defeat of ISIS and to supporting Iraq’s long-term security, stability, and prosperity.” It’s unlikely that ISIS will be truly defeated anytime soon, but it isn’t just the Sunni jihadists who continue to fight on.

Austin referenced the “deadly rocket attack in Erbil,” Iraq on February 15. Several Americans were wounded in that barrage. But the new defense secretary made no mention of the suspicion that the Iranians were behind the attack. While that remains unproven, Austin did not say anything about Iranians whatsoever during the February 19 press briefing.

It goes to show that while China is a priority for the Biden Defense Department, and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq receive some attention, other issues are considered far less important. On February 22, days after Austin’s press briefing, another round of rockets was fired at the U.S. Embassy in Iraq. It remains to be seen if and when the Biden administration will seek to respond.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.