The “man of letters” is a species that today thrives more readily in European soil than in the United States (where there is much more competition from business and entertainment) and Ales Bialiatski is one such specimen, a scholar of Belarusian literature and language, a founder of writers’ associations, a former director of the Maksim Bahdanovič Literary Museum in Minsk. He is also a nationalist in the happier sense of that often-unhappy word, having been a secret organizer of the Belarusian independence movement during the Soviet era, and he boasts of having been the first to show up at city hall in Minsk (where he was a city councilman) with a pre-Soviet Belarussian flag, the first one to be flown from the municipal building in the capital announcing the impending independence of the republic, which was realized two weeks later. Ten years ago, he was awarded the Václav Havel Human Rights Prize, and last year it was the Nobel Peace Prize.

Of course, they’ve got him locked up in a dungeon.

The official charge is financial corruption—he was just given a 10-year sentence for “cash smuggling”—but Bialiatski’s crime is his opposition to the brutal government of Alexander Lukashenko, who became Belarus’ first president in 1994 and who has held the supremacy ever since, and who is responsible for Belarus’ unhappy epithet: “Europe’s Last Dictatorship.” Lukashenko presents himself as a nationalist, too, but he is a funny kind of nationalist—one who takes his orders from Moscow and who has at times floated the idea of formal annexation by Russia. (Russia and Belarus already are joined in a “Union State” under the terms of which Belarus enjoys notional independence from and, wink-wink, equality with Russia.) Bialiatski speaks Belarusian, and the museum he once managed is dedicated to the founder of modern Belarusian literature—and he was forced out of the museum directorship by Lukashenko, who prefers and promotes Russian.

The language issue has been prominent in the Bialiatski matter. The writer-activist himself complained in an earlier proceeding that he, a Belarusian-speaking man in Belarus, was tried by a court that refused to conduct any business in that language, even though it enjoys official status. “The situation with the language used in court appears to be extraordinary,” he wrote to his judges. “I remind you that the Belarusian language is a state language, and you, as state officials, should know two state languages, including Belarusian, and not struggle to say two words. Therefore, you are obliged to speak, accordingly, in Belarusian with Belarusian-speaking citizens. For example, as provided for by the Law ‘On Appeals of Citizens’, if you write in Belarusian, any official department will respond to you in Belarusian. This put me in an unequal position with the prosecution. I was not given the opportunity to explain my position thoroughly and in detail, to dispute the unjust and senseless accusation.” The scene there was reminiscent of another writer, one whose achievement was such that he won for himself an eponymous adjective here applicable: Kafkaesque.

The nationalism of Lukashenko and his clique reminds me more than a little of the fervor of some of our homegrown self-proclaimed nationalists: I do not doubt the intensity of the sentiment involved, but it seems to me that they have not quite figured out to which country they are, in fact, attached. One only need see Sohrab Ahmari enjoying a “lighthearted moment” with Hungarian caudillo Viktor Orbán and suppressing … whatever it is he is trying to suppress … to begin to understand the psychic energy at work.

Orbán has studied the Woodrow Wilson playbook but also the Stalin playbook—he has successfully bankrupted opposition newspapers but also imposed political discipline on theaters. And one need not go the full Fidel Castro to get the job done: As one academic told The New Yorker’s Andrew Marantz: “Orbán doesn’t need to kill us, he doesn’t need to jail us. He just keeps narrowing the space of public life.”

Each case is different, but there is a family resemblance among dictators. Tyrants such as Lukashenko are always at war with their own people, and they are always at war with language, from the mundane quotidian output of journalism to the sublime work of poetry. Henry VIII, the prototype of the modern tyrant, enjoyed the services of one of England’s finest writers, Thomas More, and had him executed. (Welcome to Utopia.) One of the Spanish fascists’ first order of business was assassinating the poet Federico García Lorca, and the Franco government banned his works for decades. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics had its “Night of the Murdered Poets,” and in the course of its wide-ranging campaign of state terror that gang of homicidal idealists managed to murder, imprison, or exile many of the greatest writers subject to it, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn being the most famous of the exiles. Isaac Babel’s play Maria was shut down by the NKVD, Stalin’s secret police, during rehearsals, and the author eventually was shot and dumped into a mass grave as part of the “Great Purge.”

Pablo Neruda was headed into exile when he (probably) was murdered by the Pinochet regime, which also murdered the poet-musician Víctor Jara, the American journalist and documentarian Charles Horman, and many others. The French surrealist Robert Desnos ended up in a Nazi concentration camp. (He lived to see it liberated but died in the camp shortly thereafter of the typhus he had contracted there.) Juliano Mer-Khamis held a mirror up to Palestinian misgovernment with a staged production of Animal Farm and was assassinated for it. Salman Rushdie has been working under a death sentence since the 1980s, and a would-be assassin almost got him in August in western New York. (Rushdie was attacked while visiting the Chautauqua Institution to give a lecture; the next name in the Chautauqua guestbook is Jonah Goldberg.) The poet Heberto Padilla spent time in Fidel Castro’s gulag and died in exile; the Cuban regime has been particularly keen on locking up librarians, which should tell you all you really need to know about its character. Lukashenko’s patron, Vladimir Putin, went to extraordinary lengths to murder the journalist Anna Politkovskaya, who was finally put to death (apparently on the 10th attempt) on Putin’s birthday.

Why do tyrants hate poets? Without approving, one might at least understand murdering journalists. As the observation attributed (probably wrongly) to George Orwell has it, “Journalism is printing what someone else does not want printed; everything else is public relations.” And the whole point of being a tyrant is that you get what you want, and if there’s something you don’t want printed, then it doesn’t get printed—or you at least have the satisfaction of torturing and murdering the publisher.

The troubling thing about novelists and poets is that they cannot help but write about the real world, whatever their imaginary worlds are like, however exotic and removed from quotidian events they seem to be. More’s Utopia wasn’t as much a work of imagination as it was an indictment of contemporary social and political life; nobody at the time really needed to have Orwell’s Animal Farm explained to him; even the light entertainments of Star Trek or The Dark Knight point to events in the real world, though we modern Americans do not care enough about writers to bother murdering very many of them, and we have, thanks be to God, so far largely been spared the kind of tyrants who go in for that sort of thing. (As mentioned above, Woodrow Wilson, the pride of Princeton and the godfather of American Progressivism, was in the habit of locking up inconvenient journalists and bankrupting dissident newspapers. Adam Hochschild, writing in Mother Jones, notes the wonderfully poetic fact that Wilson’s anti-press campaign was headquartered in the building that would later become the Trump International Hotel. Donald Trump, lucky for us, lacked the things that made Wilson so dangerous: intelligence and focus.) For that reason, it never stops with the journalists and the news—a thoroughgoing tyrant has to take on the poets and the playwrights, too. And if you don’t want to read any more criticism from García Lorca or satire from Jaime Garzón—or if Thomas More lays down his pen and refuses to write what you want him to write—then there is a simple solution: No more García Lorca, no more Garzón, no more More.

Bialiatski, the imprisoned Belarusian dissident, isn’t locked up for poetry or even satire—ordinary prose will get the job done. Ralph Waldo Emerson was a capable poet, but it was his troublesome and less poetical friend Henry David Thoreau who gave us the lines for these times: “Under a government which imprisons any unjustly, the true place for a just man is also a prison.”

We know why such a figure as Lukashenko is a Putin sycophant. What is worth keeping in mind is that Putin’s American sycophants are Putin sycophants for the same reason. They are not as forthright as Lukashenko: Their habit is taking Moscow’s line and furthering Moscow’s interests—notably vis-à-vis Ukraine—right up until they reach the edge of making an open pledge of allegiance. “Of course, we condemn Putin’s war and lament his aggression, but, still, don’t you think we should make things as easy on him as possible? And don’t you know that there is corruption in the Ukrainian government?” (Don’t ask them about corruption in the Russian government, which is more of a mafia than it is an administration.) They are odd ducks, these hard-headed realists who believe that the answer to American woes is establishing a new model of politics based on 16th-century Catholic practice. These hard-headed realists—the ones who believe that Rothschild space lasers are causing wildfires in California—know that you have to break a few eggs to make an omelet. (“Where’s the omelet?” asked George Orwell.) And those poets and journalists? “Enemies of the people,” of course, whether you say it in Russian or Belarusian or English.

My friend Jay Nordlinger, who would be recognized as one of this country’s premier human-rights journalists if he did not write for National Review (and I do not mean that as a criticism of my old friends at National Review; it is an indictment of the reading public), often quotes Jeane Kirkpatrick on the subject of political prisoners: “It’s important to say their names.” Ales Bialiatski is not a household name in these United States and is unlikely to become one. But we should understand him for what he is: someone who writes things that tyrants don’t want to read, and who is in prison for arguing that his country should be free.

Economics for English Majors

When I arrived in the city still then known as Bombay in 1996, there was a great deal of restlessness in the Asian business world. Hong Kong, then unquestionably the business capital of Asia, was about to be returned to Beijing’s control, and nobody really knew how the Chinese Communist Party was going to run things in the freewheeling, dynamic, capitalistic metropolis. Some businesses were taking flight, and office rents skyrocketed in Bombay. India was then in transition, too, as the economic reforms that had begun under the government of P.V. Narasimha Rao and Manmohan Singh (it is not too late to give Singh the Nobel Prize for his world-changing work) really began to catch on, unleashing the dynamism of that young, entrepreneurial, democratic nation.

But of course, at the time nobody knew how things were going to shake out in China or in India. (Neither has turned out the way we optimists had hoped.) And some businesses were put in the position of having to choose one to make a bet on. One businessman I spoke with at the time explained his company’s eventual decision to locate most of its Asian operations in China: He explained that if his company got into a contractual dispute or regulatory litigation in India, they could be confident they would get a fair judgment under the law—someday. But it could take years. In China, on the other hand, they would be doing business under (and with) a police state, meaning that they could expect that their notional legal rights would go out the window whenever politics demanded and that the rule of law would be a polite fiction—but, while they might get a corrupt decision from time to time, they would get fast decisions. And it was not as though there were not low-level corruption (and other more rarefied corruption) in India, too, even if the courts were generally reliable and honest.

This calculus involves what economists call transaction costs, broadly understood. A transaction cost is a cost related to engaging in an economic activity, a price that typically has to be paid to some third party who is not involved in the transaction itself. For example, if you sell a house, there is a fee to be paid to the real-estate agent; similarly, if you trade a security, there is a fee to be paid that is collected neither by the buyer nor by the seller but by some third-party broker. But the economically interesting transaction costs are not simple fees. For example, if you are a software company looking to hire a programmer at $200,000 a year, it usually costs you a lot more than the $200,000 to fill the position: You have to advertise the job, interview candidates, have meetings, maybe schedule and pay for travel, etc. Transaction costs often keep firms in relationships that are less than optimal: You may have a supplier or contractor who is not making you entirely happy, but replacing one can be disruptive and expensive—and you don’t know for sure that you’ll be any happier with the new one.

Defined formally and narrowly, transaction costs relate to a relatively small and well-defined set of business processes, and they come in three general categories: research costs, negotiating costs, and enforcement costs: For example, a company with a specific engineering challenge might spend some time and money researching the best firm to handle the work, spend a little more negotiating a contract, and spend some more making sure that the terms of the contract are honored. The lines can be a little fuzzy, but you don’t want to generalize your understanding of transaction costs to encompass everything in the wider category of costs of doing business, though the two are obviously related.

In the United States, we have something called the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which makes it illegal for a U.S. firm to pay a bribe abroad, even in places where bribery is a normal and accepted part of doing business—a series of transaction costs. Most firms would prefer to do business in jurisdictions that have good government, honest courts, and the rule of law—this is such an important priority that many global firms specify New York law or London law when it comes to legally working out disputes in complex multinational business relationships. Good law, like peace, is preferable—but not at any price. Some companies will choose to do business in China or Russia or Venezuela because that’s where the business is, and they will work with corrupt or disreputable partners (this is systemic in the oil business, which is dominated by state-owned firms) because the costs of forgoing such arrangements would be economically catastrophic.

Back when he was an economist, Paul Krugman wrote a much-discussed essay titled, “Competitiveness: A Dangerous Obsession.” It remains interesting reading. Krugman argues that it is a mistake—empirically demonstrable as such—to treat countries as competing with one another the way two firms in the same market compete with one another. This was an argument written in the 1990s, when Bill Clinton and other Democrats of that ilk, along with overseas counterparts such as Tony Blair, were practicing a fashionable form of corporate progressivism, one that at least paid some lip service to fiscal responsibility, the preferability of work to public dependency, the benefits of free markets and open trade, etc.—you know: all that crazy right-wing stuff. Krugman didn’t want them to get too carried away with competitive austerity, as though that were the real danger. As Krugman argues, the United States and any of the other economically advanced countries you might pick—say, Canada—are not like Coke and Pepsi. They are not head-to-head competitors to nearly as significant an extent as they are each other’s markets and suppliers. (If the United States were Coke and Canada were Pepsi—and, sorry, it couldn’t be the other way around!—then Pepsi employees would account for 18 percent of Coke’s total outside sales, just as Canada accounts for about 18 percent of all U.S. exports, to use a wobbly analogy.) The case against destructively high taxes and cumbrous regulations isn’t that we’re worried about U.S. jobs going to Canada or Sweden or Ireland, though of course some do, but that these represent a real and ultimately shared economic loss. The United States is very lucky to have Canada as a neighbor—think of how much better off the United States would be if Mexico were as well off as Canada. What happens there matters here.

But, back to those transaction costs. Foxconn—and you remember Foxconn as one of those great Trump victories!—is making a big investment in India, where it will assemble iPhones, among other products. As it turns out, that brisk authoritarian pace of business in China brings with it some very high transaction costs, and Apple, Foxconn’s most important client, is looking to reduce its exposure to Chinese political caprice. Perhaps this will be good for India, which is arguably less liberal and less democratic today than it was in the 1990s. But in the 1990s, the optimists were mistaken in our belief that a healthy dose of capitalism would bring broader liberalism to China. There are enormous transaction costs involved in a shift of that kind for a business such as Foxconn—and if Foxconn thinks the price is worth paying, that should tell Washington and Beijing something that should be of keen interest in both capitals.

Words About Words

Kristina Karamo seems to be a real fruitcake—she apparently refuses to concede her whopping 2022 loss in the Michigan secretary of state election—so, of course, Michigan Republicans have put her in charge of the party. This is “Words About Words,” and there is a word for that, but I’m already pushing my editors’ patience when it comes to that sort of language, so I’ll look at something different.

Karamo was mocked on Twitter for writing: “The days of a milk-toast Republican Party are OVER!” (CAPITAL LETTERS MEAN I AM SERIOUS!) Milk-toast? “Ha, ha, you big dummy!” everybody chimed in. “Don’t you know it’s milquetoast?”

Except—she’s not exactly wrong.

Milk-toast is, gross as it is, a real thing, and that thing is exactly what it sounds like: toasted bread cut up and put into a bath of warm milk. This is a thing that people used to eat and, apparently, a thing that people still do eat. Lukewarm, soft, tasteless, mushy—milk-toast came to be associated with men who have the same qualities, hence the cartoon character Caspar Milquetoast, from whose name the common English adjective comes. The proper noun Caspar Milquetoast gave rise to a common noun: “Don’t be such a milquetoast.” Later, it settled into its current typically adjectival use. It is a close relation to the much older (medieval, in fact) milk-sop, a milk-sop being more or less the same thing as milk-toast: bread drenched in milk. Another relation suggesting similar weakness, insipidity, and want of robustness is milk-and-water, which dates back only to the 18th century.

Karamo may be a kook, but what she sees in milk-toast is what Harold Tucker Webster saw in it when he created Caspar Milquetoast in 1924. No harm in reverting to the original form.

Don’t be too hard on the typos. A lot of you—a lot of us—are feeling smarter than we should.

E.g.:

1. Develop Your Writing

2. *Simile

I described CPAC as being like a nude beach in the Caribbean: It seems like a lot of fun if you’ve never been, but then you get there and you see who isn’t there and who is. This produced a good laugh—and a question!

Usually, if there’s a like or as, it’s a simile. Crazy like a fox, useless as teats on a boar hog, nervous as a long-tailed cat in a room full of rocking chairs, etc. An analogy is when the qualities or principles of one thing (arrangement, system, etc.) are used to illuminate the workings of another, as in “natural selection provides an analogy to the workings of free markets,” or “the neo-Confucians understand the workings of a harmonious family as an analogy for the workings of a harmonious state.” A metaphor is a figure of speech in which a word is applied in a way that is evocative but not literal: “His eyes were blazing suns,” “He is the father of his country,” etc. That which is metaphorically the case is not literally the case, and it literally is the case that Joe Biden very often misuses the word literally.

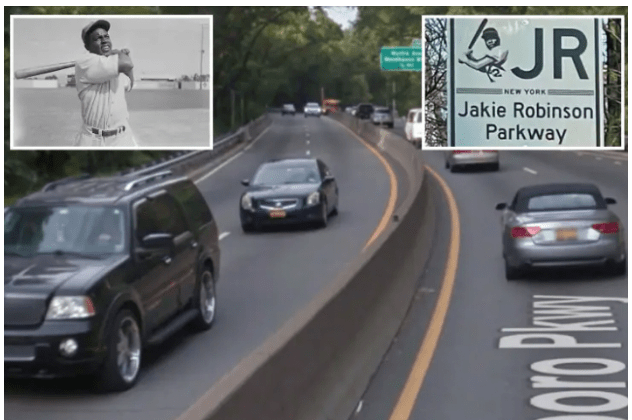

3. Forget It, Jakie, It’s Queens

Another little bit of language: In a good story about a truly horrible episode—a teacher who apparently was wrongly accused of engaging in a sexual relationship with a minor student and whose life was quite ruined by the lie—Tom Jackman of the Washington Post writes: “The first clue that Kimberly Winters, a high school English teacher, had that a former student had accused her of sexually abusing him was when Loudoun County sheriff’s deputies in full riot gear burst into her bedroom one morning with their rifles drawn.”

I am not sure what the phrase rifles drawn is supposed to mean. I understand pistols drawn: Pistols are carried in holsters, and, when you get ready to use one, you withdraw it from the holster. But rifles are not normally carried that way. Unless you are riding across the lonesome prairie with your Winchester in one of those cool saddle scabbards, rifles are pretty much drawn all the time. Maybe rifles at the ready (as opposed to slung on the back or something like that) or rifles in hand or, if it was the case, pointing rifles at her. I’d be interested in which direction those rifles were pointed.

The teacher has been vindicated and won a lawsuit seeking damages. It was not nearly enough money.

Elsewhere

Talking elections, libel lawsuits, and COVID-19 origins on The Dispatch Podcast, right here.

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

In Closing

People win enormous—shockingly large—legal settlements for all sorts of things that often seem trivial. But the teacher mentioned above, who suffered that phony sex-abuse allegation, won only $5 million in compensation. After the lawyers’ share and taxes, she’s hardly going to be set up for life, drinking fruity cocktails in Aruba, and her personal finances already were pretty well shot—because for years after the false accusation, she could not get any kind of job, even a low-paid, menial one. There is a reason “Thou shalt not bear false witness” makes the Top 10.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.