Everyone in the political world has suddenly decided that they have very strong opinions about architecture now that the Trump administration is floating an executive order to mandate “classical” architecture in federal buildings.

The draft executive order, reported last week by Architectural Record, “would require rewriting the Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture, issued in 1962, to ensure that ‘the classical architectural style shall be the preferred and default style’ for new and upgraded federal buildings.” The order is titled, inevitably, “Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again.”

This is an attempt to create an official style of architecture dictated by Donald Trump and his hangers-on. Or maybe just by Trump: the executive order notes right off the bat that “Washington and Jefferson, both amateur architects, personally oversaw the competitions to design the Capitol Building and the White House.” You can bet this was written to appeal to Trump’s vision of himself as amateur architect in chief.

This prospect has set off a spate of poorly informed comments on the history of art and architecture by people who seem to have developed an interest in the topic a week ago when it became the latest chess piece in their partisan battles.

This in itself—the subordination of art to politics—is the larger story here.

* * *

The tendentious architectural history is coming from both sides. In defense of the Modernists, a Yale historian declared that this is “one of the warning signs of fascism and … wait for it… genocide. The cult of antiquity and the imposition of monuments to a nation’s mythical glorious past precede both of those disasters.” She links to a New York Timesarticle that is much more circumspect but still says that the administration’s proposal “provokes inevitable allusions to authoritarian regimes of the past that imposed their own architectural marching orders, and dredges up images of antebellum America, when classicizing Federal architecture was all the rage.”

A historian should know that an interest in Classical art and architecture and attempts to celebrate the past have been common across many different civilizations and many different time periods. To associate Classical influences in art and architecture with Nazi sycophants like Albert Speer and Arno Breker, rather than, say, Thomas Jefferson or Michelangelo, is highly selective and misleading.

On the other side, noted architectural expert Mike Lee, a senator from Utah, defended the proposed change by singling out two particularly unattractive reinforced concrete buildings in Washington, D.C., as evidence that “new federal buildings are weird, showy, suspicious, and, most of all, ugly.” Both buildings were designed 50 years ago. He goes on to denounce “the Brutalist and Deconstructivist styles.” This attack on Brutalism and Deconstructivism, taken straight from the draft executive order, has become a popular talking point among people who had never heard of these architectural theories before last week.

But this is a highly selective attack. The executive order would specifically ban Brutalist designs, which is pretty easy since that fad petered out sometime around 1980. But Modernism encompasses a broad array of styles: the Craftsman and Prairie Styles, the International Style, Art Deco, Streamline Moderne, Futurism, Postmodernism, Minimalism, and plenty of other unique creations that defy classification as a “style.” The antipode of the hulking concrete shapes of the Brutalists, for example, is the soaring, elegantly geometric thin-shell concrete structures designed by Pier Luigi Nervi. Or consider the skeleton-winged structures of contemporary architect Santiago Calatrava, which resist categorization as any style but his own.

Frank Lloyd Wright on his own encompassed several different styles during his long and prolific career, from the low, broad Craftsman lines of his early Prairie Style homes, to the ornamented concrete blocks of the Ennis House, to the daring cantilevers of Fallingwater, to the streamlined curves of the Guggenheim Museum. And Wright, whose brilliant designs are enduringly popular, has certainly proved the lasting appeal of this architecture.

Sure, Modernists have produced some truly ugly buildings—and also some notably beautiful ones that serve as beloved icons for their cities. Or more: The Sydney Opera House, with its distinctive nested shells, is recognized the whole world round as a symbol of Australia. So these casual critics of Modernism point to a few buildings like the Federal Building in San Francisco as an appalling eyesore—based mostly on a particularly unflattering photo of its back side—while ignoring popular icons like the Transamerica Pyramid.

* * *

To be sure, the federal government has a hard time building beautiful buildings—just as it has trouble building them efficiently or on budget. That is one of the claims made in the case for classical architecture offered in City Journal last year by Catesby Leigh, in what turned out to be a preview of the new draft order. Every argument you’re hearing right now in favor of the proposed order is recycled from this article.

Leigh spends a lot of time criticizing the inefficiency of federal building projects and pinning this somehow on Modernism because of their “multistory open spaces—including glassy atria, entrance pavilions, and lobbies—which increased [operations and maintenance] costs, thanks to difficulties with cleaning and heating and cooling.” Yet he also praises, as the “epitome” of classical public architecture, the US Capitol, which has a rather notable “multistory open space” of its own—the ginormous rotunda inside its dome—which certainly poses its own difficulties with cleaning and heating and cooling.

Similarly, the draft executive order singles out as models of classical public architecture not only the Capitol but also the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, which was not exactly a model of cost-efficiency: “The Indian Treaty Room, originally the Navy’s library and reception room, cost more per square foot than any other room in the building because of its rich marble wall panels, tiled floors, 800-pound bronze sconces, and gold leaf ornamentation.”

News Flash: Government construction projects tend to be poorly managed boondoggles—today or in the 1880s, in the Modern style or in the traditional.

These examples, by the way, give the lie to many of the claims made by Leigh and those who are repeating his arguments. Take the Eisenhower Executive Office Building.

You might notice that we follow the draft executive order in using the term “classical” without any capitalization, because it is being used as a catchall term for a grab bag of traditional styles, including Romanesque, Gothic, and Spanish Colonial. It doesn’t refer specifically to Classical architecture—the architecture of ancient Greece and Rome—but basically to anything old and maybe with columns.

Such a loose definition is certainly required for the Eisenhower Building, because the Greeks and Romans never built anything like it. It is adorned with classical columns tacked onto the exterior of its bulky stone walls. But the building uses 900 one-story columns piled on top of each other in rows. In effect, the building is a series of four one-story Roman villas stacked on top of each other. The whole thing is capped off by a hulking mansard roof with massive chimneys—a style borrowed from Renaissance France.

The combination is most reminiscent not of Republican Rome but of Louis XV’s royal palace at Fontainebleau. Note the similarities.

But wait, it gets worse. The specific style of the Eisenhower Executive Office Building is French Second Empire, from the reign of Napoleon III. So this is the royal architecture of France, as adapted by imperial France.

Napoleon III favored this style when he ruled France from 1852 to 1870. The Eisenhower Building began construction in 1871. (It was renamed after President Eisenhower much later.) Leigh says that federal architecture “should embody the architectural wisdom of the ages” as opposed to making “architectural fashion statements.” But the Eisenhower building was a tribute to one of the most fleeting architectural fashions of all. As the White House’s own website for the building notes:

The French Second Empire style originated in Europe, where it first appeared during the rebuilding of Paris in the 1850s and 60s…. When [the Eisenhower Executive Office Building] was completed in 1888, the Second Empire style had fallen from favor, and Mullett’s masterpiece was perceived by capricious Victorians as only an embarrassing reminder of past whims in architectural preference.

So one of the buildings the administration’s classicists tout as an example of the timeless style appropriate to the American republic isn’t really Classical, isn’t American, isn’t republican, and was itself a fad of the day that was regarded as ugly by its contemporary audience. As to whether the building has since stood the test of time, we will only add that Henry Adams found it ugly, Harry Truman found it ugly, and we find it ugly.

* * *

In purely artistic terms, Neo-Classical architecture was at its best when architects were trying to rediscover the principles behind Classical architecture. At the beginning of the Renaissance, this was an attempt to break with the prevailing traditional architecture of the day, which we now call Gothic, in an attempt to create architecture with a greater sense of order, rationality, harmony, and serenity. Consider early examples like Filippo Brunelleschi’s Pazzi Chapel.

Neo-Classicism is at its worst when it becomes a formula applied unthinkingly from the top down, as a mere social convention. It becomes a collection of superficial ornaments to be tacked onto a building—the more the better—without regard for their original logic or meaning. This is exactly what we see in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, and it’s exactly what the draft executive order is attempting to impose.

Politically, the Neo-Classical style was at its best when it was meant to recall the virtues of Greek democracy and the Roman republic. It was at its worst when it was meant to recall the Roman Empire, as a form of nationalist aggrandizement. We mentioned earlier the contrast between the Neo-Classicism of Thomas Jefferson and the Nazi architecture of Albert Speer. Speer’s plans for Adolf Hitler were notoriously bloated and grandiose. It was Neo-Classicism with elephantiasis, intended to awe the viewer with the overwhelming power of the Leader and the State.

You couldn’t imagine a more complete contrast to this than Jefferson’s design for the Virginia State Capitol. Jefferson’s inspiration was the Maison Carrée in Nimes, which he thought dated from the Roman Republic, though it was actually built in the very early years of the Empire. But Jefferson gave it a distinctly republican treatment. The Virginia State Capitol is a simple rectangular building (the wings were added later) with a pediment and columns enclosing a portico. Its lines are kept simple, dignified, and austere. The interior plan pioneered the architecture of the newly founded republic by providing equal and separate spaces for all three branches of the state government. It is all centered on a relatively modest interior dome built around Houdon’s portrait of George Washington as Cincinnatus—the republican citizen-soldier putting aside his sword and returning to the plow.

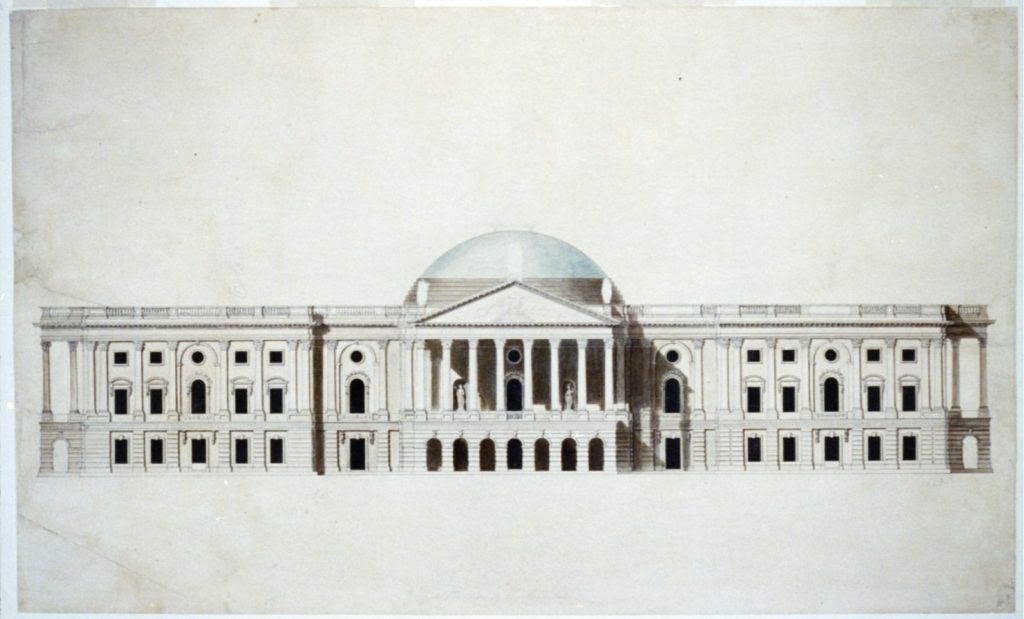

By the time the U.S. Capitol as we know it was built, American public architecture had taken on distinctly more imperial overtones, which are reflected in the overdone grandiosity of the Capitol. The original design selected by Jefferson and Washington was in keeping with Jefferson’s republican simplicity: a pedimented front with a low dome behind—very similar to Jefferson’s later Rotunda for the University of Virginia—and low, pilastered wings for the two chambers of Congress.

By the end of the 19th century, the single pediment would be flanked on the east front with banks of extra columns added to balance out a massive new dome and matched by similarly engorged pediments on expanded wings for the House and Senate. Catesby Leigh calls this repeatedly rebuilt Goliath the “nation’s greatest building.”

The Capitol’s greatness lies in its architectural excellence, starting with the perfect proportional relationship between its majestic dome and subordinate masses; its appropriately sumptuous decoration; and its supremely dignified symbolic presence in the national consciousness.

It’s hard to tell what that last clause is supposed to mean, but we can tell you that ordinary people go weeks, months, even years on end without giving any thought at all to what the Capitol building looks like.

That’s a good thing, because the proportions are far from perfect. The Capitol dome sits on top of a colonnaded drum, like the dome of St. Paul’s cathedral in London—but with another drum on top of it. The relatively simple dome of St. Paul’s is replaced by a more ornate and elongated dome more in the style of St. Peter’s in Rome. The result looks like the dome of St. Paul’s with the dome of St. Peter’s piled on top of it, and it’s not for nothing that this kind of architecture was called “wedding-cake style.”

The inner shell of the dome is a coffered ceiling, but with a giant oculus that opens to another dome higher up, with a fresco painted on it. Part of the draft executive order proposes that Trump’s “re-beautification” committee be given power to impose their tastes on the art in federal buildings, so let’s consider the art in the Capitol’s rotunda. In that dome above a dome is a giant fresco titled “The Apotheosis of Washington,” showing George Washington, draped in imperial purple, being brought up to the heavens as a god.

It was painted by Constantino Brumidi, who had previously worked on the palaces of European aristocrats. What a contrast to Washington as the farmer returning to his plow.

The U.S. Capitol is royalist art and architecture for a republic—and perhaps an early warning of the vast expansion of government that was to come.

* * *

But don’t bother to examine a folly, ask only what it accomplishes. There’s no reason to believe this executive order would result in particularly beautiful buildings or a revival of American architecture. Leigh even anticipates the most likely result: “postmodern structures that, like the Reagan building, engage traditional forms and styles to some degree.” In other words, build a glass curtain wall, slap on some pilasters, and boom—you’ve fulfilled the government’s “classical” requirements.

What this mandate would definitely accomplish is to give jobs to the people who wrote it and promoted it. Leigh is pretty open about this.

A resolutely countercultural community of classical architects has emerged in the United States in recent decades. Nowadays, however, our classicists face overwhelming indifference, if not outright opposition, within the academy and from the AIA and the legacy media. Uncle Sam needs to put these classicists to work—not only on new buildings but on the classically informed reconfiguration, wherever possible, of its many modernist structures in need of renovation. Moynihan’s Guiding Principles should be rewritten with a view to setting federal patronage apart from the anomie of our postmodern culture.

As is par for the course in the Trump era, any patronage scheme run for the benefit of a politically connected clique has to be dressed up in loud populist rhetoric. So Catesby Leigh of the Ivy League rails against “elitist architectural pieties” and tells us that federal architecture should “register with normal people, as opposed to postmodern deipnosophists.” The point would probably have come across more convincingly without the $10 word at the end.

This appeal to cultural populism has become the rallying cry for those who rush to defend the Trump administration. Sen. Lee’s article repeatedly uses the words “elite” and “elitist” to describe Modern architecture and asserts the superior wisdom of the untrained man on the street. “Most Americans may not have gone to prestigious design schools or worked at the hippest firms. On the other hand, we know ugly when we see it.” He caps this off with a Trumpian flourish, declaring the need to “drain the Swamp of its embarrassing fetish for eyesores.” So a mandate for classicism is all about ordinary people in the heartland sticking it to the degenerate elites.

This is “owning the libs” as a theory of architecture.

We’ve been warning for a while about how the left has been adopting didacticism as their dominant school of art, where every song, movie, comic book, and statue is judged by its political message. A sculpture doesn’t have to have artistic merit, so long as it has a feminist message. Poetry doesn’t have to have meter or rhyme or any poetic devices whatsoever, so long as it has a vaguely “progressive” message of affirmation. Renoir is canceled because people think he might have been sexist.

The Trump administration’s proposed mandate for classical architecture is the exact same hectoring didacticism, but from the right.

This is the first fruit of the rising “nationalist,” big-government wing of the conservative movement. Their goal is not to challenge government influence on the culture, but to use it for their own ends.

When they talk about “fight[ing] the culture war with the aim of defeating the enemy and enjoying the spoils in the form of a public square re-ordered to the common good and ultimately the Highest Good,” this is the first installment: a public square literally rebuilt to convey the dominance of “the authority of tradition.”

Advocates of the proposed executive order on architecture keep using a quote from Winston Churchill: “We shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us.” In the context of nationalist conservatism, this takes on a more ominous meaning—more George Orwell than Winston Churchill. They want to use their control of federal architecture to “shape us” in a kind of conservative social engineering.

* * *

The foolishness of this approach should be obvious. An official style imposed by executive order lasts only so long as the leader of one’s own party or faction remains in power. After that, an executive order that mandates classicism and bans Modernism can be replaced with one that mandates Modernism and bans classicism. The nationalists and their classicist hangers-on are playing a dangerous game that depends on the unrealistic assumption that power in our political system will never change hands.

The left has recently been taught a lesson about the folly of conspiring for decades to give more power to an office that ends up being occupied by someone they despise. They won’t learn that lesson, but conservatives would be advised to take it to heart—because we doubt they would like how President Sanders uses his new authority to meddle in federal architecture.

But even to the extent this clique of classicists achieves its goal, the prospect of President Trump as amateur architect in chief is bad enough. The mandate for classical architecture is billed as a way of expressing “America’s democratic values and republican virtues”—but how does it serve that goal to give the president power to impose his personal esthetic preferences from the top down?

The idea that this is about preserving and promoting American ideals is just cover for promoting top-down authoritarian social engineering—instead of the artistic diversity and creativity of a dynamic free society.

Sherri Tracinski is an architect and architectural historian based in the Charlottesville, Virginia, area. Robert Tracinski is editor of The Tracinski Letter and author of So Who Is John Galt, Anyway? A Reader’s Guide to Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged.

Photograph of FBI headquarters by Valery Sharifulin/TASS via Getty Images. Other photographs throughout the piece in the public domain.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.