Less than a year before he died, George Washington privately worried that “the Union … [was] hastening to an awful crisis.” As an elderly man, John Adams claimed there was a through line from the American Revolution to the terrors of the French Revolution. He thus lamented: “Have I not been employed in Mischief all my days?” Two years prior to his death at the hands of Aaron Burr, Alexander Hamilton lambasted the Constitution as a “frail and worthless fabric,” and decided that “the prospects of our Country are not brilliant.” By the final year of his life, Thomas Jefferson was privately referring to the federal government as the “foreign department” and contemplating whether “the dissolution of our union” would be preferable to “submission to a government without limitation of powers.”

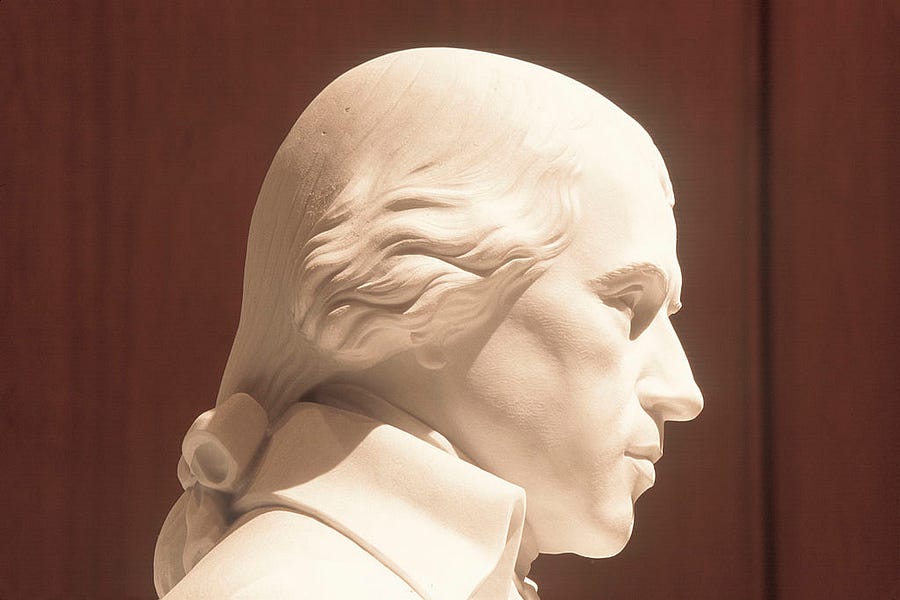

Depressing sentiments like these permeate Dennis C. Rasmussen’s new book, Fears of a Setting Sun: The Disillusionment of America’s Founders. Drawing on reams of personal correspondence between the Founders, Rasmussen persuasively argues that the vast majority of America’s Founders—including the likes of Washington, Adams, Hamilton, and Jefferson—went to their death beds disillusioned with the political order they had created. The causes of their disillusionment varied from insufficient civic virtue on the part of Americans to the growing sectional division over slavery, but their takeaways were similar: “most of the founders … came to feel deep anxiety, disappointment, and even despair about the government and the nation that they had helped to create.”

Why? And what can we learn from their profound political disillusionment?

The main lesson is to not place much hope in the amount of happiness, amity, and social progress that politics alone can produce. And the great teacher of that lesson, the lone Founder who retained a great deal of optimism about the American future, is James Madison.

The causes of disillusion.

Rasmussen notes that the Founders’ disillusionment took on many forms. For starters, their timing varied. Some, like John Adams and Alexander Hamilton, grew disillusioned with the American experiment rather quickly. Others, like Hamilton’s nemesis Thomas Jefferson, did not lose much hope in America until the very final years of life.

Moreover, the roots of their despair were unique.

George Washington—as evidenced by his famous farewell address—left the presidency despondent over the rise in partisanship. While just about all of the Founding Fathers had distaste for political parties, “none loathed them more fiercely, consistently, and sincerely than he did.” In Washington’s eyes, parties did not effectively organize interests or promote electoral accountability. Rather, parties were vehicles for citizens placing their selfish, narrow, or sectional interests above the common good. Rasmussen notes that by the end of his life, Washington privately despaired “that not only Congress but also the American people had become thoroughly and irretrievably partisan.”

The rise of partisanship made Washington highly skeptical of America’s long-term prospects. Rasmussen writes that Washington had always believed “that republican government could not survive for long” under conditions of intense partisanship. As America hurtled in that direction, Washington held fast to that belief.

Madison, on the other hand, reconciled himself with the realities of party politics early on. This was not a tall task for someone who famously wrote in Federalist No. 10 that “The latent causes of faction are … sown in the nature of man.” Madison’s sober recognition of the realities of our capacity to disagree, and to do so vehemently, kept him from thinking that the emergence of a party system threatened the Founders’ novus ordo seclorum. Parties were no more than organized factions, and the Constitution could quite capably handle factionalism without being torn asunder.

But what if parties weren’t the only problem? Could our constitutional order persist if the people themselves were wholly lacking in virtue, public spiritedness, and good character? John Adams didn’t think so. Rasmussen writes that while Adams also detested the rise of partisanship, populism, and factionalism, “the overriding source of Adams’s pessimism, the one that he returned to again and again over the course of his career, was the lack of virtue among the American people, and hence their unfitness for republican government.”

Adams wrote that “There must be a possitive [sic] Passion for the public good, the public Interest, Honour, Power, and Glory, established in the Minds of the People, or there can be no Republican Government, nor any real Liberty.” Even before the Constitution’s ratification, he was questioning whether the American people had that requisite “Passion for the public good.” Whether it was Americans’ penchant for luxuries and commercial excess, the populist politics of Jeffersonianism, or the secessionist blabber of his fellow Federalists, Adams had myriad grounds for questioning the republican virtue of Americans, and question he did. Even during his spurts of optimism, Rasmussen remarks, “the old, sober Adams disposition reemerged, reminding him that the lessons of history and the darker side of human nature could not be escaped so easily.”

Again, Madison’s realism saved him from such disillusionment. Was public virtue necessary to sustain republican government? Absolutely. As Madison remarked in Federalist No. 55, “As there is a degree of depravity in mankind which requires a certain degree of circumspection and distrust, so there are other qualities in human nature which justify a certain portion of esteem and confidence. Republican government presupposes the existence of these qualities in a higher degree than any other form.” But could we expect human beings to consistently place the public good over their private self-interest, narrow ambitions, and selfish passions? Absolutely not. Men are not angels.

Madison’s pragmatic streak also immunized him from the despair wrought by Alexander Hamilton’s and Thomas Jefferson’s clashing visions for the young nation. To varying degrees, each man came to think that the other won out. Disillusionment ensued.

Even before the Jeffersonians had come to power with the “revolution of 1800,” Hamilton was despairing over Americans’ aversion to equipping themselves for national greatness. This applied even to the Constitution that he defended so eloquently in the pages of The Federalist. While Anti-Federalists saw centralized tyranny in the new Constitution, Hamilton “was among the most disappointed in the national charter even at the outset.” In Hamilton’s eyes, the federal government (the presidency in particular) was too feeble to raise the American commercial and military might needed to challenge Europe on the stage of great power politics. The ascendance of Jeffersonianism heightened Hamilton’s despair: “Though he lived only a few years into Jefferson’s presidency, by the time of his premature death Hamilton was convinced that the Republicans had already done irreparable damage to an already-weak government and that little but disorder and dissolution could be expected thereafter.”

Jefferson, however, lived long enough to lament that Hamilton’s penchant for commercialism and political centralization had in fact won out. By the 1820s, Jefferson grew dismayed as the national bank was continually renewed, the federal government began investing in “internal improvements,” and even so-called Republicans reconciled themselves to the strengthening of federal power. By the end of his life, Jefferson routinely wrote in his correspondence of national dissolution as a preferable, albeit terrible, course of action compared to consolidation under a single central government.

Although he was a Republican through and through, Madison never grew “nearly as alarmed” as Jefferson over the commercialization of American society and the growth of federal power. He even signed off on the rechartering of the Second National Bank as president in 1816. And while he shared some of Hamilton’s disappointment with the Constitution—Madison detested the equal-state representation in the U.S. Senate, for example—he “appears to have grown genuinely reconciled to the Constitution over time in a way that Hamilton never quite did.” Why? In large part because it worked. About three months before his death, Madison concluded that “Much had already been gained in … favour” of America’s “great political experiment.” Therefore, he declared himself “far … from desponding” when it came to the experiment’s future.

What Madison got wrong.

But we would be mistaken to think Madison’s sanguinity was on the mark on every question. Madison got slavery—and its potential to destroy the Union—wrong. While Madison was distressed by the national North-South convulsions over slavery during the Missouri Crisis of 1819-1820, he did not see it as Jefferson presciently did: “the knell of the Union.” Surviving Founders like Adams and Jefferson rightly saw the growing North-South division over slavery, coupled with the emergence of the federal territories as fertile ground for those positions to come into conflict, as cause for deep concern. Madison was distressed by the Missouri Crisis and also by the nullification crisis of 1832-1833, but he continued to think that the slavery issue would ultimately work itself out peacefully. He was wrong.

Madison underestimated how very dangerous it can be for political debate to become a binary—for there to be little to no overlap between two blocs of citizens on a single issue set that dominates political discourse. As polarized as our politics are, we have not yet reached that point. But warnings of modern-day disunion, like those from David French in Divided We Fall, should not go unheeded. A politics that grows less messy and instead becomes a matter of A vs. B who see one another as existential threats, as American politics did prior to the Civil War, can overpower our constitutional order. We must guard against that.

Madison was right to remark in 1820 that “A Government like ours has so many safety-valves, giving vent to overheated passions, that it carries within itself a relief against the infirmities from which the best of human Institutions can not be exempt.” We should be grateful for and confident in the resiliency and brilliance of our system of government. We should keep our hopes and expectations for politics in check. We should not fall prey to disillusionment and despair.

Madisonianism as the antidote to disillusionment.

The roots of disillusionment lay in the outsized, inflated expectations the Founders had for American politics. Washington envisioned an independent-thinking and publicly spirited citizenry. Adams foresaw a people who could consistently place the good of the whole over their own. Hamilton sought the rapid transformation of thirteen separate sovereignties into a unified, national mass of unprecedented military and economic power. Jefferson dreamed of an idyllic yeoman farmer’s republic even as a “market revolution” was well under way.

To varying degrees, these were all fanciful goals for America’s near-term future. And when such dreams did not become realities, each Founder descended into some form of political depression.

But not Madison. Rasmussen hits the nail on the head as he connects Madison’s view of politics with his unique optimism about the American future:

“Madison simply expected less from politics than most of the other founders. He never supposed that his fellow citizens would consistently surmount partisanship or sacrifice their self-interest for the sake of the common good, nor did he long for the nation to achieve economic and military greatness on the international stage or for virtuous yeoman farmers to conduct the politics of their local ward—and this meant that he was less likely than the other founders to be disappointed in what America became.”

We would do well to imitate the fourth president’s approach to politics. This is not to say that we can’t be partisans or be committed to certain principles; Madison surely was. Madisonians accept the hard truth that politics is more about coping with problems than solving them, more about muddling through than forging boldly ahead. In that vein, we should not let our day-to-day political defeats and disappointments trick us into thinking that the American experiment is somehow a failed one.

Thomas Koenig is a recent graduate of Princeton University. Follow him on Twitter @TomsTakes98.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.