Every year at the Seders, Jews read the words of Rabban Gamliel, who instructed, “In every generation, a person must regard himself as though he personally had gone out of Egypt.” Envisioning oneself as a former Israelite slave witnessing the Ten Plagues and leaving Egypt as part of the Exodus has always been possible on a theoretical level. After all, my ancestors were among that cohort. However, this guidance is clearly about feeling a gut-level emotional connection, which is harder, because you can’t force feelings.

Still, we’re supposed to feel a divine connection. In recounting the Passover story, along with the miracles performed on the Jewish people’s behalf, we’re supposed to picture ourselves experiencing our ancestors’ history, including the Exodus. The catch is that the whole story feels completely divorced from the modern American Jewish experience.

This year will be different.

Like other immigrant groups, American Jews have found a welcoming home here and have been embraced by the larger culture. As a group, we are most certainly not enslaved. We are not relegated to Jewish-only neighborhoods. Nor have we ever been subject to evil decrees, like Pharaoh’s call to kill Israelite baby boys that launched Moses’ story.

So, as part of discussions at Seders over the years, my family has tried to make the Passover story relatable by discussing more modern slavery, including enslavement to materialism. Even if we were to discuss human trafficking this year, I’d be describing something I know from reading, not from lived experience. That is to say, I have been incredibly fortunate.

But for Passover 2020—or 5780 on the Jewish calendar—it’s like the kaleidoscope has turned. As the whole world muddles through the coronavirus pandemic, alone together, the plagues take on new meaning. They no longer feel like details from the distant past. Rather, they feel immediate and threatening.

Jews remove drops of wine from our glasses while reciting the Ten Plagues, reducing our joy as we recall the Egyptian lives lost amid our liberation. Again, it’s one thing to observe a ritual and another to viscerally relate to life in Egypt all those centuries ago. Imagine seeing potable water suddenly spoiled, labor intensive farming efforts destroyed by locusts, or first born children slain.

For the ancient Egyptians, all of these misfortunes happened without any explanation beyond divine wrath, and for that time, that might have sufficed. Perhaps it offered mourning parents some sense of meaning as they dealt with their personal tragedies, and maybe such suffering was considered normal in a way it isn’t today.

Beyond that, I find I also have new sympathy for the Israelite slaves, possibly petrified by these plagues. The Talmud says that only 20 percent of Israelite slaves actually left Egypt. According to Aish HaTorah, the rest “were so steeped in Egyptian culture that they were unwilling to join the Exodus.” But perhaps they were also terrified by radical change.

As we experience our own viral plague, the potential for palpable fear now seems more understandable. Anxious people aren’t the most rational; they regularly act out of fear. So with God appearing wrathful, inflicting 10 massive plagues on the Egyptians, perhaps those slaves wondered why God acted only after more than two centuries of oppression and slavery, whether divine protection might be fleeting, or whether God might one day turn on them, as he seemingly had on the Egyptians.

The lethality of the coronavirus, along with the way it has already disfigured national economies, feels most shocking perhaps because so many of us had grown comfortable with the illusion that we control our world, as Pharaoh believed in his own time.

Americans take it for granted that our food and water are safe, and in a world with vaccines, childhood deaths are thankfully rare. Yet now our lives are now being completely reordered to accommodate a virus as invisible to us as the Israelites’ God was to the ancient Egyptians.

While we know significantly more about our world than the ancient Egyptians did, this experience has rendered me newly empathetic to the generation that endured the plagues. And as we once again read Rabban Gamliel’s words this week, I will effortlessly envision myself among my ancestors, anxious as Egypt is plunged into darkness and food insecurity, recognizing I have no control over the numerous plagues happening around me, and praying that everything soon comes out right.

Melissa Langsam Braunstein, a former U.S. State Department speechwriter, is now an independent writer in the Washington, D.C., area.

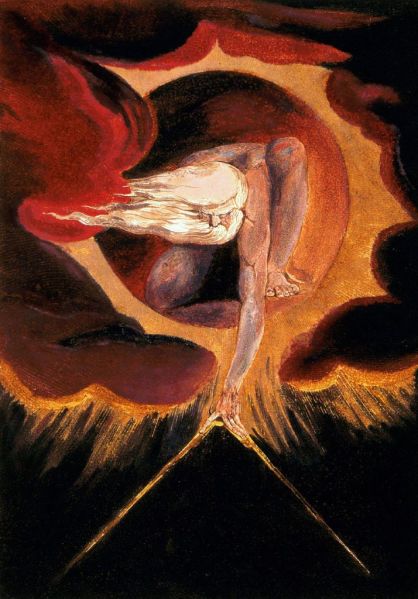

Photo of a painting in the Jewish Museum of Venice by Godong/Universal Images Group/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.