Lately certain Trump-skeptical conservatives have worried that the “vibe” of the Republican presidential primary is beginning to look concerningly 2016-ish.

To which I say: I wish.

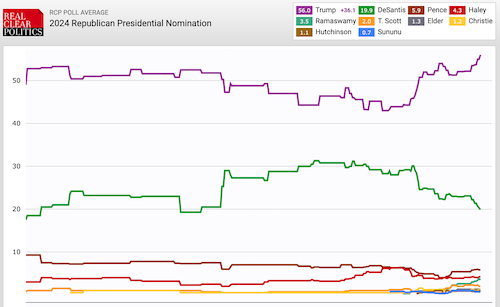

Have you seen the polls? Here’s what the RealClearPolitics average looks like as I write this.

Trump is at 56 percent, his highest mark to date, and holds his biggest lead yet over Ron DeSantis. In his first run for president Trump didn’t consistently top 30 percent in primary polling until December 2015 and didn’t establish himself as a clear favorite for the nomination until he won South Carolina. As late as November of that year, he trailed Ben Carson in polling.

I long for the days when he was that vulnerable.

In context, dismissing DeSantis’ candidacy as “Cruz 2.0” is an insult to Ted Cruz, who remained within single digits of Trump all the way to April 2016. DeSantis might never get that close, let alone defeat Trump in multiple primaries.

Having said all that, I understand why Trump skeptics are having flashbacks.

He’s dominating early media coverage of the primary.

He has a base of diehard support that’s as solid as granite, beyond the power of reason or morality to crack.

He’ll benefit if no-hoper candidates keep piling into the field, splintering the anti-Trump vote among them. Some aspirants are delusional, unable to accept their unpopularity with Republican voters; some are obvious “break glass in case DeSantis tanks” options; some are so obscure that they’d need millennia of free TV time for them to raise their name ID meaningfully. But they can all lure handfuls of voters away from DeSantis, making the task of catching Trump that much harder.

Oh, and should Trump win the nomination, he’s likely to face one of the few Democrats in America who’s as miserably unpopular as he is, giving him a real chance of winning.

There are parallels to 2016 in all of that. But the nature of that primary and this one are distinct.

Both races pose the same question to Republican voters that I described back in February: Why not something different this time?

But the baseline against which “something different” is measured has changed radically in eight years.

Trump’s victory in 2016 can be understood as the Republican electorate finally growing exhausted with the soft libertarianism of the party’s post-Reagan politics. The GOP leadership didn’t share the base’s preferences on matters like immigration and entitlements, and it lacked the relish for cultural conflict that right-wing media and its consumers felt. All of which might have been tolerable if that leadership had at least reliably delivered presidential victories, but the only Republican to prevail in the 24 years between 1992 and 2016 was the not-fondly-remembered George W. Bush.

Believing it had little left to lose, the base was ready for something different. Trump was … different, stylistically and substantively.

Ted Cruz believed those substantive differences would be Trump’s downfall. He assumed, quite reasonably, that the right-wing base would apply the same exacting ideological litmus test of “true conservatism” to the upstart that so many other Republican politicians had flunked in years prior by proving squishy on policy. Cruz had passed that test with flying colors, which is why he spent most of the campaign believing that Trump would eventually collapse and Trump’s voters would switch to him.

What he discovered was that populist conservatives don’t care much about conservatism when they’re getting a raw enough dose of populism. Trump’s substantive differences with GOP orthodoxy on policy weren’t disqualifying after all.

The theory of DeSantis’ nascent candidacy, à la 2016, is that Republicans are once again ready for something different. But this time the contrast that’s supposedly going to beat Trump has to do with style, not substance.

Yes, yes, I know, DeSantis has spent this spring laser-focused on piling up legislative victories. Isn’t that all about drawing a substantive contrast with Trump? “We already saw in Ted Cruz’s 2016 campaign the limits of ideological correctness,” Ross Douthat wrote recently, worried that DeSantis is repeating Cruz’s mistake. “There are Republican primary voters who cast ballots with a matrix of conservative positions in their heads but not enough to overcome the appeal of the Trump persona, and a campaign against him won’t prosper if its main selling point is just True Conservatism 2.0.”

I think that misunderstands what DeSantis is trying to achieve by piling up legislative wins. He’s not so much trying to outdo Trump on policy as to neutralize policy as a factor in the primary, which also explains why he tends to adopt Trump’s own position on fraught subjects. The governor is running on competence and electability, implicitly promising Trump voters that they can get all the same stuff they like from a government with DeSantis in charge that they’d get from Trump, minus the many self-sabotaging distractions. “You don’t need to worry about either of us being good on policy,” he’s telling voters. “Focus instead on which of us is more likely to win and then to run a tight ship in office.”

That’s a stylistic pitch. Whereas Trump and Cruz offered two different visions of what Republican policy and politics should be, DeSantis is conceding that primary voters were right to prefer Trump’s vision in 2016. The question of what the party should be is settled. The question that remains is who’s most capable of gaining and wielding power to realize that vision.

Even DeSantis’ recent break with Trump over banning abortion after six weeks has less to do with the substance of the policy than with style, I think. He can’t match Trump’s charismatic macho bluster in confronting liberals, so he aims to compensate by presenting himself as less compromising on policy than even Trump is. That’s the subtext of his critique of Trump over COVID restrictions as well: Anyone can err in making a policy choice but to be swayed by a sinister liberal icon like Anthony Fauci is unforgivable. Trump didn’t “fight,” DeSantis will.

That’s different from trying to beat Trump on substance by offering “True Conservatism 2.0.” Unlike some people, the governor is smart enough to recognize that’s hopeless.

A campaign focused on stylistic contrasts in demonstrating resolve is one important way 2024 won’t look like 2016. The other is that no one is under any illusions at this point about who or what Donald Trump is.

Centuries from now, schoolchildren will marvel at how many people believed he could become a responsible steward as president after he was first elected. He’ll “grow in office,” we were told. He’ll be surrounded by “adults.” Trump himself hinted from time to time during the campaign that his persona in office would differ from his persona as a candidate.

Even after he’d been sworn in, desperate pundits would seize on instances where he briefly behaved more or less normally to proclaim that this, at last, was the moment he had truly become president.

No one says that anymore. There’s no hopeful scenario for a second Trump term.

A Republican voter considering Trump in the 2016 primary had to ask himself whether he preferred a charismatic TV star preaching protectionism and isolationism to a lackluster programmatic conservative in the Ted Cruz mold. A Republican considering Trump in the 2024 primary has to ask himself whether he prefers a twice-impeached coup plotter to a much younger populist who’s gung-ho to wage the sort of culture war that the base craves.

And that voter will need to somehow confront the fact that the party has had not one, not two, but three disappointing elections under Trump’s leadership, something DeSantis is already eager to remind them of.

Many things flow from those differences.

It’s true, as Douthat writes, that Republicans seem to be making a number of other vintage 2016 mistakes as the governor prepares to enter the race. Some donors seem put off by his populism and are eyeing no-hoper alternatives; those no-hopers appear inclined to stay in the race long past the point of viability, squatting on votes that might otherwise go to DeSantis; Republican movers and shakers have grown fatalistic too soon about a Trump victory, risking a self-fulfilling prophecy; and the media, as demonstrated by CNN’s recent town hall, sounds a little too excited to have him back in the mix.

I’m naively optimistic that none of those parallels will hold for long if DeSantis shows momentum in the polls this summer, though.

Donors surely recognize the risk of Trump prevailing over a divided field again, having learned from painful experience. Deprived of their money, and not wanting to bear responsibility for facilitating a third Trump nomination if the race between him and DeSantis is tight, most of the no-hopers will quit before the primaries. The fatalism will fade as DeSantis’ polling improves and Trump’s legal troubles mount. And the media will be more sober in covering Trump this time around, if only to avoid the ferocious backlash CNN is now experiencing.

Although 2024 polling doesn’t yet show a meaningful difference between Trump and DeSantis when pitted against Biden, that too could change as the governor becomes better known. The more proof there is that DeSantis is right when he claims the GOP will fare better with him at the top of the ticket, the more electability is likely to weigh on Republican voters. For instance:

If Trump is at the top of the ticket, Democrats would have a five-point advantage in the generic congressional ballot, leading Republicans 47 to 42 percent. Without Trump, Democrats and Republicans are deadlocked at 44 percent, according to the survey from WPA Intelligence released Wednesday and obtained by National Review.

…

While Biden is unpopular with voters, Trump is even more so. If the election were held today, 47 percent of voters would choose Biden while only 40 percent would choose Trump. Twelve percent are undecided.

…

Additionally, if Trump were to be charged with a crime either in Georgia or by special counsel Jack Smith at the federal level, his support would drop to 39 percent overall while Biden’s support would be upped to 49 or 50 percent respectively.

“You have basically three people at this point that are credible in this whole thing,” DeSantis reportedly told donors on a conference call on Thursday. “Biden, Trump, and me. And I think of those three, two have a chance to get elected president—Biden and me, based on all the data in the swing states, which is not great for the former president and probably insurmountable because people aren’t going to change their view of him.”

In 2016 the question of Trump’s electability and his effect on Republican candidates down ballot was a black box during the primary. Three grim election cycles and one insurrection later, any primary voter who isn’t already committed to him knows they’re inviting electoral disaster for the GOP if they fail to unite behind his most formidable challenger in the primary.

That doesn’t guarantee that the anti-Trump vote will consolidate this time, but it improves the odds. And don’t forget, unlike eight years ago, this time many Trump-hating Democrats in Iowa may have a say in how the GOP caucus there shakes out.

In short, 2024 will differ from 2016 because Republican voters know precisely what they’re getting this time.

Which is not to say that Trump won’t win anyway.

That’s because the party has changed in eight years. Voters who find Trump insufferable and dangerous have fled, others drawn to his authoritarian charisma have flooded in.

At the risk of belaboring a point I made elsewhere this week, his viciousness and amorality are no longer vices that right-wingers are expected to tolerate uneasily and then put aside on Election Day in the interests of Republican victory, as was true in 2016. They’ve become affirmative reasons to support him, evidence of his righteous brutality. To object morally to him or conclude that he’s unfit for office is now tantamount to confessing your left-wing sympathies.

Convincing a cult of personality that’s grown more feral over time to replace the personality at its center because you just passed a DEI bill or whatever is a tall ask.

DeSantis’ “Trump without the nonsense” pitch might have succeeded in 2016, when Republican voters were willing to overlook his nonsense in the interest of trying something radically different. But in 2024, that nonsense is part of the GOP’s tribal identity.

It may turn out that all the legislative victories in the world can’t hope to impress a right-wing electorate as much as being indicted by multiple Democratic prosecutors does. If I’m right that DeSantis’ many policy achievements will function mainly as a proxy for his ability to antagonize the left, he may find himself trumped nonetheless by Trump’s even more impressive achievement in getting himself criminally charged by liberals numerous times.

In fact, the governor could plausibly find himself reliving a very particular chapter of the 2016 primary. Recall that, for the last four months of 2015, it was Ben Carson who looked to be Trump’s most formidable challenger. But Carson failed to impress once Republican voters took a hard look at him and he faded, clearing the way for Ted Cruz’s ascent.

DeSantis might not receive much of a bounce after he announces his candidacy next week or, if he does get one, it could fade quickly. It’s also possible, if not likely, that the other non-Trump candidates will pile on him at the first (and probably Trump-less) Republican debate, ruining his introduction to undecided voters. If he falters, some of his donors and supporters who are desperate to unseat Trump won’t be patient while he tries to recover. They’ll abandon ship in their haste to find a more viable alternative, leaving DeSantis to suffer Carson’s fate.

In that sense, it really might be 2016 all over again. And this time, there’s unlikely to be a Cruz in the rest of the field who can at least make Trump sweat a bit before he prevails.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.