A few days ago, the leader of the free world recounted a conversation he’d had at the 2021 G7 summit with French President François Mitterrand—who’s been dead since 1996.

He meant Emmanuel Macron, you might say. People misspeak sometimes. That’s true, just as it’s also true that people sometimes lose their train of thought. But when the “people” in question are of a certain age and their train of thought derails in an unusually garish way …

… it’s fair to wonder, as most Americans do, whether there’s more to these missteps than the usual pitfalls of extemporaneous speech. There must be a reason that the president would decline an opportunity to answer questions before a gigantic audience of voters this weekend in the thick of a reelection campaign, and we all have the same suspicions about what that reason might be.

Any discussion of weak political leadership in modern America properly begins with the health of Joe Biden, a liability which, I’m convinced, will end up costing him a second term this fall. But Biden’s condition obscures an underappreciated aspect of his party: Democrats enjoy relatively strong leadership in other institutional roles.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer has brokered multiple legislative deals with Republicans on big-ticket matters like infrastructure—no easy feat in an era in which the right treats any compromise with Democrats as treacherous. House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries has held his liberal and progressive factions together on numerous key votes that have led to embarrassment for Republicans, most notably the effort to oust then-Speaker Kevin McCarthy. And the Democratic National Committee under Chairman Jaime Harrison crushed its GOP counterpart last year in both fundraising and cash on hand.

Whether the head of the Democratic Party is in control of events remains, and will remain, an open question. But the DNC and the party’s House and Senate caucuses continue to run smoothly and professionally, with next-to-no internal tumult that might impede their respective agendas.

In the other party, it’s the opposite.

Yesterday, we considered how Trump’s third coronation has removed whatever institutional obstacles might have remained to his total control of the GOP. And then, as if to prove the point, news from both the House and Senate Republican conferences and the Republican National Committee broke that seemed to confirm that the former president is the only person left with any real influence over events.

Institutionally, up and down the ranks, the GOP has a debilitating crisis of leadership. It’s not an accident. And more often than not, the leaders in question aren’t to blame.

Well, they’re sometimes to blame. Partly.

House Speaker Mike Johnson, for instance, is surely to blame for the fact that he can’t do basic math.

On Tuesday night, Johnson chose to move ahead with a floor vote on impeaching Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas knowing that the margin would be very close. Party-line votes are always close given the current makeup of the House, but following George Santos’ expulsion, Kevin McCarthy and Bill Johnson’s resignations, and Steve Scalise’s absence for cancer treatments, the GOP majority could afford only a few defections. Things got hairier when three House Republicans announced earlier in the day that they’d vote no on impeachment, for sound constitutional reasons.

That left the GOP poised for a 215-214 victory, assuming Democrat Al Green missed the vote as he recuperated from surgery he had last week. But Green shocked the world by rolling into the House chamber, still in hospital attire, to cast a vote in defense of Mayorkas. The three Republican “no” votes wouldn’t budge. And so the House deadlocked, 215-215, forcing a member of the GOP leadership to switch his own vote to “no” for the sake of being able to bring up impeachment again at a later date. The effort to oust Mayorkas had failed.

Losing a vote has become standard practice for Johnson, a neat trick given that a speaker typically doesn’t put a bill on the floor unless he knows that he has a majority in favor. But losing in a matter as high profile as an impeachment vote is so humiliating that it left the media scrambling for analogies to historic disasters.

Johnson and his conference weren’t done, though. After losing on Mayorkas, they called a vote on legislation that would send billions of dollars in aid to Israel and … lost that one too.

That bill saw a comfortable majority of the House in favor and would have passed easily under normal rules, but the chamber no longer operates normally with the GOP in charge. A number of Republicans on the Rules Committee opposed the bill because it didn’t offset the aid to Israel with spending cuts elsewhere. Unable to move those holdouts, and lacking the Committee’s support, Johnson opted to move the legislation under “suspension of the rules,” which requires a two-thirds majority rather than a simple majority for passage.

The final tally didn’t come close. Even his own members couldn’t understand what he was thinking.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Capitol, the Mitch McConnell era appeared to be quietly winding down.

McConnell’s problem isn’t that he can’t do math; it’s that the math in his conference no longer favors him. He might stay on as minority leader a while longer, but the Republican fiasco over Sen. James Lankford’s bipartisan border security bill suggests that he, like Johnson, has lost control of his members in a meaningful way. He’s always had a restive populist minority of Ron Johnsons and Ted Cruzes to deal with, but the fact that serious conservatives like John Cornyn and Thom Tillis wilted so quickly this time after Donald Trump declared his opposition to Lankford’s bill suggests McConnell’s influence over the Senate GOP has waned.

In fact, the sudden collapse of Lankford's deal may come to be seen as a test of strength between McConnell and Trump that tipped the balance of power among Senate Republicans decisively and durably toward the former/future president. Politico describes the mood in the conference today as “open rebellion,” with multiple McConnell enemies seizing the opportunity to call on him to resign. The Washington Post marveled on Wednesday that dissension in the ranks and the inability of an impotent leader to resolve it had begun to make the Senate GOP resemble the House GOP, “a rudderless caucus incapable of following through on basic pledges.”

It’s no exaggeration to say that Democrats currently lack a negotiating partner in both chambers. Neither Mike Johnson nor the legendary Mitch McConnell can reliably deliver votes anymore.

While all of this was happening on Tuesday evening, news broke that the technical leader of the Republican Party was preparing to resign.

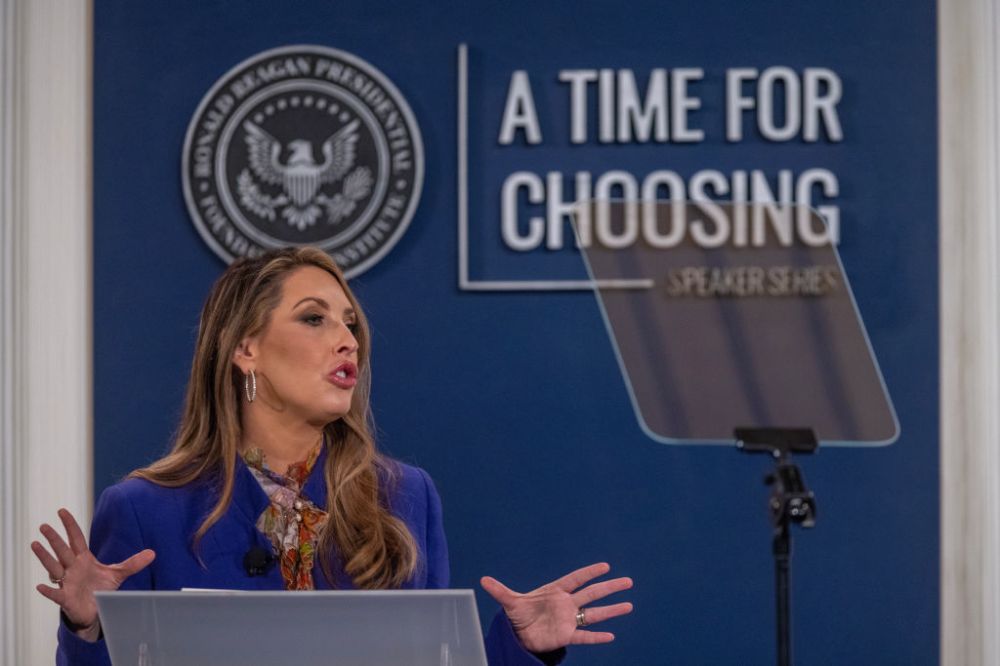

RNC Chair Ronna McDaniel has always been viewed suspiciously by the populist right, partly because the organization she runs is a flagship of the cursed “establishment” and partly because she carries the even more cursed name of “Romney.” (Or did, anyway.) But hostility to her rose after the GOP underperformed dismally in the 2022 midterms, enough so that McDaniel faced a serious leadership challenge early last year.

She survived that and, with support from her patron Donald Trump, has gone on to become one of the longest-serving RNC chairs in party history. Lately, however, patience with her organization has run thin. Last year turned out to be the worst fundraising year for the RNC in nearly a decade; dubiously large expenditures on nonsense like limousines and floral arrangements have compounded the cash crunch; and McDaniel resisted Trump’s lobbying to end the Republican primary debates early and divert the money being spent on them toward, ahem, “stopping the steal.”

In the end, I suspect MAGA types simply resented that an old-guard Republican like her continued to exert nominal control over the GOP’s top body after populists had taken over the rest of the party. And so, although she’s being coy about it for now, McDaniel will reportedly be departing sometime in the next few weeks. If Trump gets his way—and who are we kidding—she will be replaced by a 2020 election conspiracy theorist.

McDaniel, McConnell, and (Mike) Johnson: Each has become a leader in name only, each is unlikely to last in their position through the end of 2024, and each has emerged as a convenient scapegoat for their party’s cultish populist base for political failures rightly attributable to the GOP’s true leader.

And each deserves it as a karmic matter, having abetted the rise of that leader in appalling ways.

It’s not Ronna McDaniel’s fault that her party didn’t perform better in the midterms.

It wasn’t McDaniel who elevated toxic cranks like Kari Lake and Blake Masters in swing-state primaries, fumbling away races that a generic Republican would have won. It wasn’t McDaniel who alienated top-tier Senate prospects like New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu and former Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey, scaring them off from running for fear of a vigorous primary from a “stop the steal” opponent. And it wasn’t McDaniel who swooped into Georgia on the eve of the 2021 runoffs with a message that discouraged some Republicans from voting.

It wasn’t McDaniel who demanded that the GOP’s governing body help cover her astronomical legal bills, and it wasn’t McDaniel who hoovered up millions of dollars in donations that might otherwise have gone to the RNC with her own political organs instead.

In a party that now exists to serve one man, it was inevitable that the influence and fundraising of that party’s top organization would decline. Why would anyone who supports the GOP or seeks influence within it choose to give money to the RNC instead of to Donald Trump?

I doubt most Trump cultists can even explain McDaniel’s job duties. She’s become a lightning rod to them simply because they need someone to blame beside Trump for the party’s woeful performance in elections since 2018. But don’t feel bad for her: Ronna McDaniel spent seven years nominally presiding over Trump’s hollowing out of her party. Like many other Republicans, she was willing to assist him because she saw personal advantage in doing so. She’s a villain. It’s good and just that she’s come to be treated like one by the element of the right she enabled.

Mitch McConnell too. Although the decline of the Senate GOP isn’t his fault either.

McConnell is a victim of shifting ideological tides. His electoral project since the start of the Tea Party era has been to maximize the number of Republicans in the Senate while minimizing the number of rabble-rousing populists who might potentially obstruct serious congressional business for grandstanding purposes. He’s been fighting a losing battle, though: Where once he had only to worry about “conservatarians” like Cruz, Lee, and Rand Paul, he now has a growing nationalist cohort of figures like Josh Hawley and J.D. Vance to contend with. And as Trump goes about picking favorites in this year’s Senate primaries, it’s apt to grow further.

Despite his prodigious fundraising ability, McConnell’s influence in getting electable conservatives nominated in races against Trump’s wishes has shrunk to the point that he’s been left muttering impotently about “candidate quality.” But he’s reconciled himself to the new populist direction of the party enough to have spent many millions of dollars propping up Vance’s Senate campaign in 2022, believing that even the most awful Republican is preferable to an additional Democrat in the chamber.

He’s reaping the whirlwind for that this week, as Vance rants incessantly about the Lankford border security deal and accompanying aid for Ukraine that McConnell covets.

McConnell is a perpetual scapegoat among the grassroots for Republican failures, partly because he made an enemy of Trump over January 6 and partly because his age and traditional conservatism make him a figurehead of the pre-Trump GOP that populists loathe. But he deserves it as well. He helped get Trump elected in 2016 by holding open a Supreme Court seat through the election and very well might help get him reelected in 2024 by not rallying his conference to disqualify him from holding future office at his second impeachment trial three years ago.

If and when the Trump-influenced isolationists in his conference or in the other chamber successfully block a last-ditch effort to fund Ukraine’s military this week, I hope he takes a moment to appreciate his own role in having inadvertently midwifed what his party has become.

As for the House GOP, it should go without saying that the dysfunction there isn’t Mike Johnson’s fault.

If not for preexisting Republican dysfunction, he wouldn’t have his job to begin with. You may recall that his predecessor needed 15 rounds of balloting last January to win the gavel, then became the first speaker in American history to be ousted. And once the office was vacant, it took the better part of a month and numerous failed candidacies from the likes of Steve Scalise and Jim Jordan before Johnson was chosen in desperation.

His problem isn’t his inability to do math. (Although that is a problem.) His problem is that he has a bare majority in the House to work with and a conference that’s divided between three blocs: the good soldiers who’ll follow the leadership’s efforts to legislate; the small but influential cohort of small-government ideologues like Chip Roy and Thomas Massie willing to go their own way; and the media-friendly MAGA performance artists who take inspiration from Trump in disrupting “business as usual” through acts of rebellion.

A majority with a three-vote margin—a running policy dispute between conservatives and populists, and a split personality between governing and theatrical obstruction of government—is not going to perform efficiently, irrespective of who leads it. Given how fragile his grasp on power is, Johnson has little choice but to allow the one true leader in the party to lead him around by the nose in opposing compromises like the new border bill even though it presents a fine opportunity for him to show that he’s capable of achieving big things in legislating on a high priority for the country.

Eventually, Johnson will be scapegoated for the House GOP’s dysfunction by his members, just as Kevin McCarthy was before him, and probably forced out of the job. And when he is, the ignominy will be richly deserved: Lest we forget, Johnson was one of the key capos in Trump’s coup plot following the 2020 election.

Like McConnell and McDaniel, he’s presumably quietly haunted by how much bigger his party’s footprint in Congress might have been if not for Trump’s influence. Like McConnell and McDaniel, he’s made his peace with the direction of this party anyway, for selfish reasons. And like McConnell and McDaniel, he’ll pay for it ultimately.

Three weak and weakening leaders. But it couldn’t have ended for them any other way, could it?

The point of authoritarianism is to co-opt or eliminate institutions capable of limiting one’s power. It’s the essence of Trump’s presidential campaign. All the blather about policy, like 60 percent tariffs on Chinese imports, seems half-baked and perfunctory even by the usual MAGA standards. Where the candidate comes alive is when he talks about ruining those who would hold him accountable for things he’s done or otherwise resist his attempts to work his will.

To complain that there are no longer any negotiating partners for Democrats in Congress, as Sen. Chris Murphy did this week, is to acknowledge that Trump’s authoritarian effort has achieved its goal—internally, at least. The goal of the movement he leads isn’t to pass legislation, Lord knows, or even to win elections except at the very top. The goal is to ensure that there’s one—and only one—leader in the political organization he runs. If you want to deal with the Republican Party in any respect, legislatively or otherwise, you deal with him.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.