C. S. Lewis argued that every particular sinful disposition is related to “some good impulse of which it is the excess or perversion.” The appetite for justice becomes wrath, the desire to achieve material prosperity becomes avarice or envy, the normal sexual drive becomes an abnormal one, the impulse toward achievement or excellence becomes pride, the mother of sins. This was very close to the view of St. Augustine and of Aristotle before him. Wealth, health, love—all good when pursued in the right way toward the right ends in a well-ordered life, but all invitations to catastrophe to the disordered soul. Even friendship has its perils, in Lewis’ view: “Friendship (as the ancients saw) can be a school of virtue, but also (as they did not see) a school of vice. It is ambivalent. It makes good men better and bad men worse.”

Dedication, commitment, principle, courage—these are not always virtues in a public man. Sen. Barry Goldwater famously insisted: “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice! And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue!” The esteemed gentleman from Arizona was wrong on both counts, but there is real truth to the underlying point: Ends matter. Mother Teresa and Osama bin Laden both were religious extremists, John Brown and John Wilkes Booth both engaged in acts of political violence, Winston Churchill and Mao Zedong both were political leaders of great resolve.

Loyalty is a two-edged sword, because the virtue is necessarily conditional: Loyalty to whom or to what? To what degree? To the exclusion of which other virtues? St. Peter, after getting off to a rough start (three times!) was a loyalist to the end—but, then, so was Eva Braun.

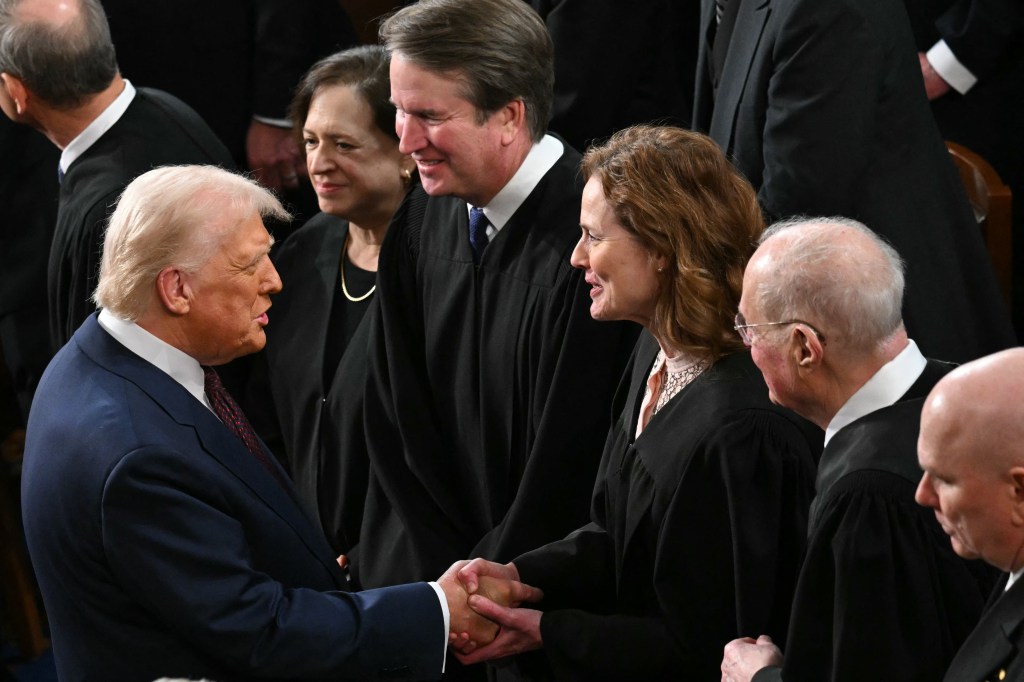

Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who joined with the chief justice to rule against Trump in the matter of his attempt to unilaterally freeze certain federal spending, is a great loyalist—but not the kind of loyalist Donald Trump’s ghastly little sycophants demand that she be. Justice Barrett is loyal to her oath of office, to the law, to the Constitution, to certain principles governing her view of the judge’s role in American life—all of which amounts to approximately squat in the Trumpist mind, which demands only—exclusively—that she be loyal to Trump, and that she practice that loyalty by giving him what he wants in court, the statute books—and the Constitution—be damned.

The usual dopes demand that she give Trump what he wants because he is “the man who put her on the Supreme Court.” Mike Davis of the Article III Project (not the author of Late Victorian Holocausts; his organization works to recruit Trump-friendly judges) sneers that the justice is “weak and timid” and, because he is a right-wing public intellectual in 2025, that “she is a rattled law professor with her head up her ass.” Davis, a former clerk for Justice Neil Gorsuch, presumably is not as titanically stupid as he sounds, but there is a reason Justice Barrett is on the Supreme Court and he is a right-wing media gadfly who describes his job as “punching back at the left’s attacks.”

There is a word for men such as Davis et al.: subjects.

A citizen has many different loyalties and obligations, sometimes complementary and sometimes rivalrous: to the state, to duties voluntarily entered into, to a particular people and way of life, to an ethos, and, in the case of the U.S. citizen, to the Constitution, which binds all of those others together in different ways. A subject’s loyalty is simpler in that it binds him only to a man—a king, traditionally. From time to time the peckerwood-trash caucus talks about Donald Trump as though he were a king, but the same kind of ritual self-abasement can be found even in doddering republics such as ours. My colleague Jonah Goldberg believes that the ceremonial ass-kissing is in reality a kind of political self-defense mechanism: While the Republican Party and the so-called conservative movement are dominated by Trump, one cannot safely profess dedication or loyalty to an idea, a policy, or a set of principles—or even to the Constitution, which Trump has explicitly marked for “termination” when it means that baby can’t have what baby want—because any principle or policy one pledges oneself to today will be on the outs with Trump tomorrow, because Trump is a fickle, unprincipled clown with the impulse control of one of those federal cocaine monkeys and the attention span of a goldfish in a bowl full of meth.

The ritual subordination of one man to another—kneeling before the king, kissing the godfather’s ring, whatever—is a big deal in Trump’s world, and it is one of many expressions of the weird homoerotic character of Trumpist rhetoric and propaganda, from its depictions of the president as an oiled-up bodybuilder to its invocation of tropes from a subspecies of homosexual pornography. It is not about public policy: It is about public men’s self-conception of themselves as men. It plays out in a weird way in the modern social-media context, but it is part of a very old kind of politics—Julius Caesar adopting Octavian, that kind of thing. Justice Barrett, who seems for all the world to be a psychologically normal, highly intelligent woman in her early 50s, apparently does not feel the kind of self-abasing compulsion that Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio do, that Mike Davis celebrates.

She has the soul of a citizen, not the soul of a subject.

We have seen this before and of late, especially, it seems, with highly accomplished women who grew up in the conservative legal movement. Danielle R. Sassoon, the acting U.S. attorney in Manhattan who resigned rather than follow the directive to drop a corruption case against the mayor of New York City in order to compel him to support the Trump administration’s immigration program, was a Trump appointee and a product of the Federalist Society. She did the right thing for a civil servant to do in such a situation: Rather than carrying out an order that she believed to be illegal or unethical, and rather than engaging in a campaign of covert insubordination to undermine her bosses, she quit her job and gave her reasons. Justice Barrett, who has lifetime tenure on the Supreme Court—and her case is an excellent argument for lifetime tenure!—is compelled neither to bend the knee to Trump nor to resign in protest. She can do what it is Supreme Court judges are supposed to do:

I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter. So help me God.

Trump, of course, has contempt for all of the above: oaths, the Constitution, true faith and allegiance, obligations, the duties of the office, God. He is profoundly corrupt in himself and is a source of corruption in others—moral and intellectual corruption—from Vice President J.D. Vance to the Republican leadership to a lot of famous names associated with conservative journals, radio programs, and television shows. What explains that? Ambition and avarice, to be sure—Trumpism is a grift par excellence—but also an obvious lack of republican self-respect, a deficient or deformed sense of citizenship, just as Lewis’ sin was deformed virtue. And it leads not to new and innovative political forms but back to old ones: client-patron relationships, paternalism, caudillo-ism, serfdom.

Lewis was not what we would call a libertarian, but there was a streak of libertarianism in him:

To live his life in his own way, to call his house his castle, to enjoy the fruits of his own labour, to educate his children as his conscience directs, to save for their prosperity after his death — these are wishes deeply ingrained in civilised man. Their realization is almost as necessary to our virtues as to our happiness. From their total frustration disastrous results both moral and psychological might follow.

And here we are.

Lewis identified courage as the lynchpin of the virtues: “Courage is not simply one of the virtues but the form of every virtue at the testing point, which means at the point of highest reality.” I am sure that Justice Barrett has that kind of courage, but it is good that we do not have to rely only on the courage of public officials under stress. Mike Pence did the right thing—once—when it really counted, but there is very little about the man that would make me eager to bet the security or stability of the republic on a 99.9 percent yes-man such as he. We have institutions such as lifetime tenure for Supreme Court justices to help to fortify their virtues, and more important institutions, such as the division of powers among three branches of government, to frustrate the worst sort of thing that would-be caudillos such as Trump and their sycophants can think up. But if we took seriously the line of thinking we see in the likes of Mike Davis—that Supreme Court justices owe Trump something personally because he appointed them, just as others have argued that the speaker of the House should be a Trump loyalist exclusive of his other duties because Trump supported his bid for the speakership—proceeding in accord would dissolve those fortifications.

And, really, for what? So that we can have tariffs on Canada on Mondays, Wednesday, and Fridays but not on Tuesdays and Thursdays? So that American evangelicals can feel good about their fealty to a thrice-married former casino-cum-strip-club owner and cameo performer in pornographic films? So that we can have red hats serving the role of red armbands?

That cannot be it. But men who have the souls of serfs are never satisfied until they have a means of expressing their serfdom. And if that has to happen while they’re dancing to the Village People and “YMCA,” well, these are weird times and those are weird people.

Economics for English Majors

Rep. Chris Deluzio, in the week’s dumbest column, warns Democrats against “anti-tariff absolutism.” He might as well have warned his fellow Keystone Stater Sen. John Fetterman against being a fashion victim or warn me against doing too many pull-ups all at once—there is no danger of Democrats evolving into anti-tariff absolutists. The Democratic tariff policy in place the last time the Democrats were in a position to make tariff policy was not only a lot like Donald Trump’s tariff policy, it was literally Donald Trump’s tariff policy, the bulk of which Joe Biden and his congressional allies defended and fortified.

Before Trump, there was Barack Obama, who described his protectionist corporate-welfare policies as “economic patriotism,” while his henchmen (infamously, Ohio Gov. Ted Strickland) denounced Mitt Romney as an “economic traitor” for (mostly) supporting free trade in goods, services, and capital. Obama gave speeches in which he invoked Teddy Roosevelt’s “new nationalism,” and, in doing so, he was carrying on a long tradition in the Democratic Party. Let me tag in Jonah Goldberg for a round:

Wise policy makers grasp the trade-offs and act accordingly. Trump is telling the hurt people to suck up “the little disturbance” to save the soul of America. This is just the latest version of a very old argument that many presidents have invoked to defend statist policies: “Economic patriotism.”

It’s worth noting that “economic patriotism” has long been rightly understood as a left-wing or progressive concept. If policies—the Green New Deal, Obamacare, etc.— were obviously great for everyone’s bottom line, you wouldn’t need to appeal to patriotism to sell them. In the last decade, Joe Biden, Barack Obama, Elizabeth Warren, and Bernie Sanders have all floated versions of it. Woodrow Wilson’s war socialism and FDR’s New Deal were both sold as the point of praxis between best policy and highest patriotic principle. Now that argument has become bipartisan.

Liberal trade relations have made Americans measurably richer (by lowering real prices) and have, contra the esteemed gentleman from Pennsylvania, also made the workers in the countries we trade with better off. The representative of the fine people of Economy, Pa., should know better!

But, no, Doofus in da House writes in the New York Times:

American companies offshored production to take advantage of cheap labor in countries like Mexico, which for decades have crushed independent unions to keep wages rock bottom.

Those “rock bottom” wages in Mexico hit an all-time high in January and are likely to continue to rise. Hourly wages for factory workers are on a long-term upward trajectory. The statutory minimum wage (not a policy I favor, but indicative of the political direction) has been going up more in Mexico than in other comparable countries, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development: “[R]eal minimum wages increased by 86.6%, making Mexico the country with the highest real minimum wage increase since pre-pandemic levels in the entire organization.” That doesn’t sound like a very successful conspiracy against the workers. Goodness knows Mexico has its problems—corruption, misgovernance, crime—but trade with the United States has made Mexican workers better off, just as it has made American workers better off.

The basic economics of trade is always the same: Comparative advantage and specialization allow resources to be put to their most productive uses, which makes the whole trading universe better off. Those gains will not be distributed equally, but it’s easier to satisfy people cutting up a bigger pie than a smaller pie.

“If you oppose all tariffs, you are essentially signaling that you are comfortable with exploited foreign workers making your stuff at the expense of American workers,” Rep. Deluzio writes. That’s dumb populist horsepucky, of course: Foreign workers are “exploited” by having incomes they wouldn’t otherwise have, and American consumers are “exploited” by plentiful goods available at low prices—boo f’n’ hoo. It would be more accurate to say that tariffs raise taxes on American consumers in order to protect the interests of politically influential firms and industries, and, in many cases, are a tax on the poor to subsidize the wealthy. Corporate managers and financiers are—surprise!—a lot more effective when it comes to collecting rents than factory workers usually are.

Tariffs are not the only form of restriction on trade, and there are other trade restrictions that are more defensible. Of course, nobody thinks the Chinese should be manufacturing our tanks or ICBMs or sensitive digital doohickeys, but tariffs aren’t how you go about fixing that kind of problem. Tariffs are just a good way to allow relatively low-performing domestic firms and industries to raise their prices. That’s why certain business interests like them—and it is why politicians like them, too.

But for poor households, consumption is a zero-sum game: If a $10 pair of shoes now costs $17, that’s $7 that isn’t available for food, rent, medical care, school supplies, etc. And maybe we should think about families for whom that matters, from time to time.

Words About Words

Whenever I hear somebody say the words “Trump Derangement Syndrome,” I just assume that they have a big, neon sign floating over their heads reading: “I’m Stupid, So Treat Me Like I’m Stupid.”

It is a very useful heuristic, even when it comes to people who are, however exasperating, not actually stupid.

In Other Wordiness …

I really dislike Rep. Deluzio’s framing above, which is, of course, a classic strawman setup. There might be someone in official Washington who “opposes all tariffs”—some froggy libertarian out there on the fringe of the GOP—but there are not a lot of just hardcore free-trade Democrats in Congress, and Republicans are about as bad these days. I oppose all tariffs, because tariffs are a national sales tax and, in the 21st century, a dumb way to collect revenue. If you want to protect U.S. automakers from Korean competition, just ban the Korean imports and be done with it. It would be a dumb policy, but a slightly less dumb policy than a larger federal tax on cars. Transparency, honesty, directness—these are to be encouraged in policymaking. But opacity and complexity are a way to provide benefits to those with political connections and to powerful firms and investors with the resources to game the system.

There is a lot to debate about tariffs, beginning with: Are tariffs supposed to be a revenue program or a protectionist program? Because those are ultimately mutually exclusive goals: If your tariff succeeds in keeping imports out of the marketplace, then you don’t get the revenue; if you’re getting a lot of revenue, then you’re not doing a lot of protecting.

But as with Trump apologists who position themselves as the alternative to “market fundamentalists” and progressives who rail against “unfettered capitalism,” “anti-tariff absolutism” is a fundamentally dishonest way of talking about the question, unless you happen to be talking to me or like seven other free-trade guys wandering around. The Democrats haven’t nominated a free-trade guy since Bill Clinton, and he often was a pretty wan and reserved one at that. I don’t think California Gov. Gavin Newsom is out there secretly reading Milton Friedman by flashlight under the bed covers.

Congress should be more than a debating society, but, if you’re going to have a debate, have the debate we’re having.

Elsewhere

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can check out “How the World Works,” a series of interviews on work I’m doing for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, here.

In Closing

Since I am in a very C. S. Lewis-y kind of mood, a thought: One of the remarkable things about Lewis is how he writes in such a sensible way and tone about Christianity, the central claims of which are—and I write this as a believer—bananas. Everything about Christianity is implausible, wrong, upside-down, and what the Christian faith asks of us, in thought and in deed, is absurd. And, yes, there is that irresistible Something in it.

Lewis begins Mere Christianity with a very straightforward argument for moral universals:

Every one has heard people quarrelling. Sometimes it sounds funny and sometimes it sounds merely unpleasant; but however it sounds, I believe we can learn something very important from listening to the kind of things they say. They say things like this: ‘How’d you like it if anyone did the same to you?’ — ‘That’s my seat, I was there first’ — ‘Leave him alone, he isn’t doing you any harm’ — ‘Why should you shove in first?’ — ‘Give me a bit of your orange, I gave you a bit of mine’ — ‘Come on, you promised.’ People say things like that every day, educated people as well as uneducated, and children as well as grown-ups.

Now what interests me about all these remarks is that the man who makes them is not merely saying that the other man’s behaviour does not happen to please him. He is appealing to some kind of standard of behaviour which he expects the other man to know about. And the other man very seldom replies: ‘To hell with your standard.’ Nearly always he tries to make out that what he has been doing does not really go against the standard, or that if it does there is some special excuse. He pretends there is some special reason in this particular case why the person who took the seat first should not keep it, or that things were quite different when he was given the bit of orange, or that something has turned up which lets him off keeping his promise. It looks, in fact, very much as if both parties had in mind some kind of Law or Rule of fair play or decent behaviour or morality or whatever you like to call it, about which they really agreed. And they have. If they had not, they might, of course, fight like animals, but they could not quarrel in the human sense of the word. Quarrelling means trying to show that the other man is in the wrong. And there would be no sense in trying to do that unless you and he had some sort of agreement as to what Right and Wrong are; just as there would be no sense in saying that a footballer had committed a foul unless there was some agreement about the rules of football.

Rhetorically, it is very clever, very carefully constructed stuff. It reminds me a little of two colleagues whose writing I very much admire, Jay Nordlinger and Ramesh Ponnuru, each of whom writes with a style that is so carefully sanded down and polished that it doesn’t feel like a style at all. Each of them has a gift for producing sentences that feel inevitable. I, on the other hand, write a lot of 5,000-word articles with 222-word opening sentences with 16 adjectives and 39 adverbs and em dashes and parentheticals and all that—the meat-ax to their scalpels. For Lewis, the fact that the underlying material is so difficult makes the matter-of-fact-isn’t-it-obvious? style almost a necessity. How else would you talk about what he’s talking about?

I need to work some of that approach into my stuff. I have a tendency to go from zero to thermonuclear in about six words, which is fun—I hope!—but not always the best way to get ’er done.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.