Hey,

Let’s get right to it.

While I was at the Aspen Ideas Festival, the topic of artificial intelligence dominated many panels. I don’t want to wade into the actual details of AI policy. I’ll just say that it’s a legitimately important issue on any number of fronts. Indeed, that’s the only statement I can make about it that approaches anything like a consensus opinion.

What is remarkable to me is that consensus. There haven’t been many times in human history when elites and non-elites alike sense that society is on the cusp of something really big and transformative. There have been even fewer times when that sense of things is accurate. The best examples of such moments are probably various millenarian panics. The Taiping Rebellion—led by Hong Xiuquan, who claimed to be Jesus’ brother—was a really weird mix of Christian and Chinese eschatology that led to around 25 million deaths in the 19th century. The Anabaptist Dominion of Münster (1534-35) in Germany was a pretty wild, albeit short-lived, party. The Xhosa cattle-killing movement in what is now South Africa was even weirder. A Xhosa prophetess, Nongqawuse, sparked a riot of crop destruction and—you guessed it—cattle slaughter, justified in the belief that such actions would cause the dead to rise and purge the continent of white settlers.

As a non-paying reader, you are receiving a truncated version of The G-File. You can read Jonah’s full newsletter by becoming a member here.

There have been plenty of others, and we’ll save the spelunking in those myriad apocalyptic rabbit holes for another time. But it’s worth noting that such panics are pretty common in secular, modern societies, too. And I don’t just mean weird cults like the Branch Davidians or the Hale-Boppers. Most readers are old enough to remember the “Y2K” panic, when all of our technology was expected to go bonkers for lack of a couple of extra decimal points of computer code.

There are other moments of quasi-millenarian panic—or confidence!—that are more relevant. Since the rise of liberal democratic capitalism, there have been moments when lots of people convinced themselves that we were on the brink of vast civilizational change (in no small part because they craved vast civilizational change). Again, such convictions predate the liberal democratic capitalist revolution, but they take a specific form in our era. Mussolini, Hitler, Lenin, and Mao were convinced that the existing order was poised to be swept away and that they’d do the sweeping. Karl Marx is the most influential of these secular prophets. His influence—as undeserved as it was—rested on a kind of millenarian logic rebranded as “scientific socialism.” As if by an Iron Law only he could interpret, the bourgeois order was destined to be swept aside. Even among non-Marxist progressives, this underlying assumption that massive change was unavoidable and nigh drove a lot of ideological and political assumptions. I am not exaggerating when I say FDR’s “New Deal” tapped into this conviction. What is a New Deal other than a fresh start? A do-over? A reimagining of how the system works?

Collectivism and statism have periodically been hailed as the Next Big Thing. Sometimes this is a sincere belief. But I also think that freedom—capitalism, modernity, whatever you want to call it—has a tendency to nurture the belief that if we can just replace the current system with some form of collective nationalized politics, the state or the “movement” will fill the holes in our souls.

Anne Morrow Lindbergh, the wife of the more famous Lindbergh, wrote an instant bestseller called The Wave of the Future: A Confession of Faith (I appreciate the honesty of the subtitle). According to Lindbergh, collectivism and statism were coming under many different names—fascism, communism, nationalism, socialism—and there was nothing we could do about it. “The evils we deplore in these systems are not in themselves the future; they are scum on the wave of the future,” Lindbergh wrote. As with the French Revolution, we should accept a lot of egg-breaking in exchange for the Great Omelet to come.

A lot of this can best be understood as Ferris Buellerism. See a parade marching your way? Jump in front and proclaim yourself the leader. Don’t see a parade yet? Pretend it’s coming anyway, and act as if you’re its leader-in-waiting. I’ve written a lot about this sort of thing when it comes to the new right and, before that, Hillary Clinton’s “politics of meaning,” or Obama’s allegedly “new politics.”

What interests me about all of the AI talk is how it already appears to be a rich cocktail of these different political and non-political impulses, and people are getting drunk on it. Some are angry drunks, some happy. But signs of the drinking binge are as obvious as dozens of pages of Xeroxed asses strewn across the office the day after the office Christmas party.

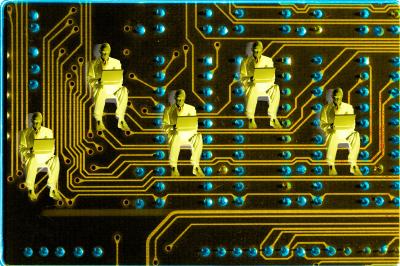

Already we hear about various AI-worshipping cults sprouting up. We’re constantly told, in the words of Chris Barry, a vice president at Microsoft: “The era of AI is here, ushering in a transformative wave with potential to touch every facet of our lives. … It is not just a technological advancement; it is a societal shift.” My friend and AEI colleague Jim Pethokoukis sometimes sounds like he believes AI will be some kind of magical philosopher’s stone and fountain of youth in one. There’s even a healthy dose of Cold War, Sputnik-style panic that the Chinese will beat us to AI nirvana and refuse to let us in. On the flipside, there’s an almost religious fear that AI will enslave humanity. I’ve lost count of the number of times fairly normal, sober-sounding people have floated the fear that a Butlerian Jihad against the thinking machines may be necessary.

Again, they all might be right. Though I don’t think the nirvana and toiling in AI’s silicon mines scenarios are compatible.

But I can’t shake my skepticism. I admit this might just be a personality quirk of mine. I reflexively dislike groupthink and moral panics, not to mention industrial policy and talk of new New Deals and, relatedly, I really dig liberal democratic capitalism. So I could be too enamored with my priors to see what is obvious to others.

But take a look at this piece from Axios founders Jim VandeHei and Mike Allen. “We've talked to scores of CEOs, government officials and AI executives over the past few months,” they report. “Based on those conversations, we pieced together specific steps the White House, Congress, businesses and workers could take now to get ahead of the high-velocity change that's unspooling.” They reassure us that “None requires regulation or dramatic shifts. All require vastly more political and public awareness, and high-level AI sophistication.”

Okay, sounds good. But then they inform us that we need a “Marshall Plan” for AI.

A what now? When I think of policies that involve “dramatic shifts” I tend to think of things like the Marshall Plan. But wait, a mere Marshall Plan is inadequate to the challenge we face. They quote Scott Rosenberg, Axios’ own managing editor for tech, who explains that what America really needs is “a combination of the Marshall Plan, the GI Bill, the New Deal — the social programs and international aid efforts needed to make AI work for the U.S. domestically and globally.”

Oh. Is that all? No dramatic shifts or regulation were involved in those things.

I heard VandeHei (who I like) on TV the other day explaining that the CEOs and other AI researchers he talks to want this kind of Marshall Plan/GI Bill/New Deal trifecta. He makes it sound like they must be right.

But hold on. If a journalist proclaimed that the auto or steel industry needed a “Marshall Plan” or “New Deal” would anybody—anybody without a pretty obvious vested interest—say “Oh well, if that’s what they want, who am I to argue?” If the editors of the leading media outlets got together and insisted we need a Marshall Plan for journalism, would we say, “Well, they’re the experts. We have no choice.”?

I’m not saying there’s anything inherently corrupt or sinister in these broad appeals for—I’m sorry, Jim—drastic shifts and regulatory overhauls. But you don’t have to be a student of public choice theory to be skeptical that the titans of a specific industry have a self-serving agenda when they invite an historic public-private partnership for the benefit of that industry.

The brilliant Marxist historian Gabriel Kolko overturned the myths of the Progressive Era by pointing out that the just-so story of heroic government rescuing America from rapacious capitalism was actually mutually agreed-upon spin by Progressive bureaucrats and rapacious capitalists. For instance, in high school, I had to read Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, which told the story of how the meat packers—Big Meat—were greedy villains immiserating workers and poisoning consumers until the feds stepped in to save us. The problem is that it was a lie. Even Sinclair said as much: “The Federal inspection of meat was, historically, established at the packers’ request,” he admitted in 1906. “It is maintained and paid for by the people of the United States for the benefit of the packers.” Similarly, Kolko wrote, “The reality of the matter, of course, is that the big packers were warm friends of regulation, especially when it primarily affected their innumerable small competitors.” As I wrote about in great detail in Liberal Fascism, this was the approach of big business throughout the Progressive Era and New Deal. When Mark Zuckerberg pleaded with Congress for Big Tech to be regulated, he was updating the same playbook.

I honestly don’t know the right approach to AI. I don’t even know if there is a single right approach, given that AI—and the pursuit of it—will have disparate impacts in all sorts of areas. Saying we should have a single “AI policy” is probably like saying we should have a single internet policy or transportation policy. That, of course, is ridiculous. Regulations for, say, pornography and jet packs will be different from regulations for math tutorial videos and donkeys.

But when I hear smart people saying that AI is both the Wave of the Future, requiring fundamental transformations of government policy, and that it won’t require drastic shifts or more regulation, I am fairly certain that there’s some millenarian hysteria out there.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.