Elections are inherently dramatic events. There is a winner and a loser, and an urge to draw conclusions. But that urge can easily lead us to overread ephemeral blips while overlooking more durable patterns, and mistake the nature of the drama we are witnessing.

That risk is particularly great in analyzing the 2022 midterms, because the drama that needs explaining is a story of what didn’t happen. The president’s party usually does far worse in midterm elections than the Democrats did in this one, and no one seems to think this election was different because the Democrats offered the public an appealing case for themselves. It was different because Republicans somehow failed to translate voter unhappiness with the status quo into votes for change. The question is why.

If an answer is going to get beyond candidate personalities, which matter but can’t be the whole story, it should particularly help explain the results in the House of Representatives. Only a third of the Senate is up for election in any midterm, and not necessarily the third most representative of the country at large. But the entire House is on the ballot, and its contours are decided by a vast national electorate, which this year exceeded 100 million voters. Broad trends across that immense population might tell some useful tales.

This year’s popular vote for the House is coming into sharp relief only now, almost three weeks after Election Day, as a number of Western states that count votes at a maddeningly glacial pace are finally completing their tallies. The overall picture is straightforward: Republicans won a raw popular majority of just more than 3 percentage points, and will likely have 222 seats in the House next year, while the Democrats have 213. This is essentially a mirror image of the Democrats’ narrow win in the 2020 House elections and their tiny majority in the current House. Since 1994, the party not holding the presidency has ended up with an average of 231 House seats in midterm elections, and the GOP’s 222 is the second-worst showing by such a party over these three decades (exceeded only by the Democrats in the 2002 elections, in the wake of September 11).

The leading explanations for this result have so far emphasized three structural factors (money, turnout, and geographic voter concentration) and two substantive factors (abortion and Trumpism), some of which are more persuasive than others. It’s worth thinking through each of them briefly, but also considering one further factor rooted in the less than dramatic nature of results: the possibility that a status quo election reflects the persistence of dissatisfaction rather than the absence of it. Maybe voters didn’t choose change in this election because they weren’t actually offered change, but the very same options they faced and turned down last time.

Systemic Causes

The structural explanations for Republican underperformance are particularly popular with Republicans themselves. A week after the election, I attended an event at which five leading House Republicans (all soon-to-be chairing key committees or subcommittees) were interviewed. All of them, to varying degrees, pointed to a huge Democratic money advantage and a supposed Democratic advantage in voter turnout as the chief causes of the disappointing election results. These have been prominent in conversations among Republicans in Washington since Election Day.

But the case for a Democratic money advantage does not explain the pattern of wins and losses in the House. The relatively greater dependence of Republicans on centralized committees rather than individual-candidate fundraising likely put them at a disadvantage in some marginal races. But this was more of a challenge for Senate candidates, where some close races required strategic decisions about how to allocate money. Those decisions are easy to criticize in retrospect and certainly might have been wrong. In House races, it’s more difficult to track and compare overall campaign-related spending, combining outside groups and official campaign funds, but the available evidence of expenditures does not suggest a huge gap. Between August and Election Day, for instance, Democrats spent about $330 million on advertising in House races and Republicans spent about $316 million, according to AdImpact, a firm that tracks political advertising. That difference is not significant enough to explain the relatively weak Republican showing.

The case for a turnout disadvantage is weaker still. The exit polls suggest Republican turnout was actually stronger than Democratic turnout, and that turnout was stronger in Republican strongholds than Democratic ones. There is so far no evidence of surging turnout among left-leaning demographic groups or in Democratic areas. Instead, it looks like Republicans did relatively poorly with self-identified independents.

What’s more, the low-turnout story is at odds with the third structural explanation of the midterm results, which begins from the fact that Republicans actually won a majority of the popular vote for the House this year. In fact, the Republican vote share, at roughly 52 percent, was larger than the Republican share of seats in the next House, which will be more like 51 percent. The last time Republicans got about that percentage of the vote, in 2016, they ended with 241 House seats. If that had happened this time, we wouldn’t be looking for explanations of Republican underperformance.

Clearly, the disparity between the popular vote margin and the margin of seats won is part of what made this election a disappointment for the GOP. And so, this view suggests, maybe Republicans are now beginning to suffer the kind of underrepresentation that Democrats have long experienced in the House. Their voters are increasingly concentrated in dark red districts, where they run up huge margins, but absent from more purple swing districts.

This explanation, as articulated for example by my American Enterprise Institute colleague Sean Trende, makes a serious and plausible case. And it suggests that the evolution of the party coalitions may mean Republicans will increasingly find themselves underrepresented in the House. Republicans, Trende argues, “may be suffering a representational penalty in rural areas similar to the penalty Democrats have suffered in urban districts,” and that pattern may persist as a new electoral reality for the right, in which Republicans win more votes than seats on a regular basis.

Maybe. But this election does not offer enough evidence to think so, and there are reasons to be skeptical. The scale of the disproportion between Republican vote share and seat share in this election was quite small, it was not unprecedented, and in the context of the history of the modern Congress it was nowhere near the challenge the Democrats have faced.

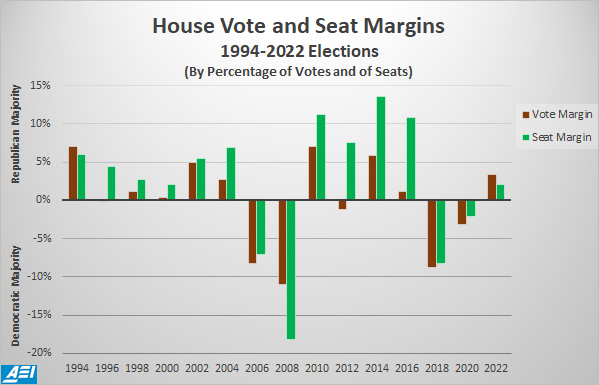

If we think about the modern Congress as an era of relatively narrow and unstable majorities, we would have to say it began with the Republican takeover of the House in the 1994 midterm elections. In the House, unlike the Senate, the nearly three decades since then have been a Republican-dominated period, with the GOP winning House majorities in 11 of 15 elections over that time. The chart below traces margins of victory in House elections since the 1994 election in terms of both a raw percentage of the national House popular vote and a percentage of House seats won. (By “raw percentage” I just mean that the figures for vote margins are not adjusted to account for uncontested seats; such adjustments, which are perfectly reasonable to make and very useful for some purposes, would not alter the basic patterns and relationships captured by the chart over this period, or the general picture of the House popular vote this year.) For clarity, and maybe to score a cheap point, I’ve represented Republican majorities as positive numbers and Democratic ones as negative.

In these 15 elections, Republicans have won a greater share of votes than of seats while winning a House majority twice, in 1994 and this year. They also did it once when Democrats won the House, in 2008.

The Democrats, meanwhile, have won a greater percentage of votes than seats in 12 of those 15 elections, including three of the four elections in which they have won House majorities. The most memorable of these dozen instances was likely in the 2012 election, when Democrats won a majority of the vote but Republicans won a majority of the seats in the House—indeed, a significantly bigger majority than they won this year, ending up with 234 seats. Democrats also won a tiny popular majority in 1996 (edging Republicans by about .03 percent of the raw national vote in that essentially tied election) while Republicans won a 19-seat majority. That is what an overrepresented party looks like in the House.

One reason to be skeptical that this year marks the beginning of a new era of Republican underrepresentation in the House, therefore, is that the previous two times that Republicans have won a greater share of votes than of seats in the modern House did not signal a new pattern or a durable trend; each lasted just one election and the pattern of Democratic underrepresentation soon resumed. Another is that the difference between the GOP’s vote and seat margin this year is quite modest.

Maybe this will turn out to be the beginning of a new era of Republican underrepresentation in our party system, but count me skeptical for now. An overconcentration of Republican voters did contribute to the disappointing seat margin achieved in this election, but we should not assume it represents a durable new reality, or even that it is more a cause than a symptom of what happened this time.

Turning Off Voters

Structural explanations of election results are often ways for disappointed candidates to avoid talking about their own failings. To confront those failings, Republicans have to acknowledge that much of the story of the midterms is that, even with an unpopular Democrat in the White House, Republicans were not attractive to potentially winnable voters.

One way to see this is by looking at House districts that Joe Biden only narrowly won in 2020. These are often the most ripe for picking off in midterms. As Amy Walter of the Cook Political Report noted recently, in the 2018 midterms the Democrats won more than 80 percent of the House districts that Donald Trump had won by 5 percentage points or less two years earlier. But this year, Republicans won only about a third of the districts Biden won by 5 points or less in 2020.

This is not because President Biden has held on to the approval of these marginal voters, but because Republicans could not win their support. As the exit polls demonstrated, the 10 percent of the electorate that described itself as “somewhat disapproving” of President Biden on Election Day broke for Democrats in the midterm—narrowly but enough to make a difference in swing districts, where these voters tend to live.

There is no simple way to find out just why the GOP did not make the sale with these winnable voters. The two most commonly offered explanations have been abortion politics in the wake of the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe and the repellant power of Donald Trump. Both surely have some explanatory force.

The politics of a court decision to uphold Roe would probably have been even worse for Republicans, as social conservatives would have been left dispirited and outraged. But abortion unquestionably energized Democrats some in key regions of the country, and it’s reasonable to assume that this was especially the case in suburban districts that voted narrowly for Biden in 2020.

Pro-lifers should not deny or ignore this straightforward reality, or else we will fail to learn the lessons necessary to advance our cause in the coming years. The failure of pro-life ballot measures in Kentucky and Montana, along with the success of a pro-abortion measure in Michigan (and less surprising such successes in California and Vermont), offer ample reason to think that abortion also helped some Democratic House candidates.

Overturning Roe was more than worth some House seats, and it’s possible that the passage of time will show concerned voters that the sky will not fall in the absence of Roe, and indeed that giving abortion back to state legislatures will result in the kinds of moderate outcomes most voters want. The Democrats could easily overreach if they take this election to mean that voters want radically permissive abortion regimes everywhere. But Republicans would be just as mistaken to assume abortion didn’t hurt them this time. Abortion politics in a post-Roe world will be a politics of persuasion, and Republicans need to better gear themselves for that reality.

Trump and Trumpism also plainly contributed to the result. As my AEI colleague Philip Wallach has shown, in competitive House districts this year, “candidates bearing Trump endorsements underperformed their baseline by a whopping five points, while Republicans who were without Trump’s blessing overperformed their baseline by 2.2 points — a remarkable difference of more than seven points.”

This election showed that winnable swing voters really do exist in meaningful numbers, and that they are open to Republicans, including quite conservative Republicans, but also that they are plainly turned off by Trump and his stamp on the GOP. That has been clear since the beginning of the Trump era, but it should now be utterly undeniable.

A less Trumpy Republican Party would have ended up with a less narrow House majority next year.

Polarized Deadlock

Ultimately, however, that very narrowness is a factor not to be ignored. The tiny Republican House majority in the next Congress, and the peculiar fact that it is an exact mirror image of the tiny Democratic House majority in this Congress, marks a historical peculiarity that should call our attention to something important about this moment in our politics.

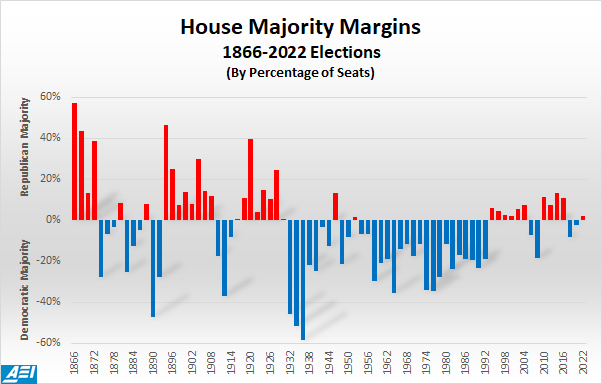

The chart below shows the size of Republican and Democratic House majorities since the emergence of the modern party duopoly in the wake of the Civil War. Majorities are measured as percentages of seats in the House, to account for the growth in the number of House members over this period (as new states were admitted, and as the House increased its membership after every census until 1910).

The era of the modern Congress, since 1994, stands out for the narrowness of its majorities. The average House majority in this period has been 32 seats. The average from 1866 through 1992 had been 79 seats.

But the current Congress and the next one are, in combination, downright unique. We have never before seen such narrow House majorities for two Congresses in a row. Majorities of 2 percent or fewer seats have occurred only four previous times since 1866 (in the 1916, 1930, 1952, and 2000 elections) and in each case they lasted for only one Congress. Two nearly tied Houses in a row, with a minuscule majority held by one party and then the other, is something we have not experienced before.

This might cast the drama of the midterm in a different light, suggesting that rather than making a stark choice given new structural conditions or distinct issue priorities, voters have declined to choose any direction at all, given the options the two parties have offered them. The Senate election fits this story too: For all the high stakes and intense battles, the next Senate will look nearly identical to the current one.

In other words, we might be finding it hard to explain the message voters were sending, whether by considering systemic or substantive factors, because the message they meant for both parties was “no.” And this was their message in 2020 as well. That year, the Democrats ran on a progressive agenda while Republicans offered Trumpism, and voters rejected both, giving neither party a mandate. But the Democrats tried to govern as if they had large majorities, and Republicans acted as if Trumpism was popular, so that in essence the question before the public in 2022 was the same as in 2020—and so was the public’s answer. Voters again gave neither party a mandate for governing on its own and effectively demanded to be offered something else.

This interpretation of the outcome doesn’t come naturally, because a status quo election feels like an affirmation and not a rejection. But it’s no coincidence that even the Democrats themselves can’t seem to tell a story of this election that involves the public expressing confidence in their governance. Voters got the same deadlocked Congress for two more years, yet no one suggests they just want more of the same.

This midterm was a vote of no confidence in both parties, just as the 2020 election was. And there is reason to think we will only keep seeing such votes of no confidence as long as the parties offer voters the same choice between a repugnant Trumpism and a rabid cultural progressivism.

Surely neither party would be foolish enough to make that mistake in 2024. Right?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.