Young Israel—an Orthodox Jewish synagogue in Willowbrook, Staten Island—has stood since 1966. Jay Marcus, its founding rabbi, joined the New York community when there were only 40 Orthodox Jewish families there. By 2016, Young Israel had grown to around 1,000 members. Though not Orthodox myself, I attended Hebrew School at Young Israel, and weekend retreats where Rabbi Marcus still presided over “Stump the Rabbi” sessions. (We never stumped him.) Today, the synagogue offers religious services, classes, and even two mikvot, or ritual pools, one for people and another for utensils. Several other Orthodox congregations call Willowbrook home.

No one should be complacent about the status of America’s Orthodox Jews, but any serious account of American liberalism should consider how communities like Young Israel have been able to thrive here. Regime Change: Toward a Postliberal Future, by the political philosophy scholar Patrick Deneen, doesn’t.

The book does attend to people of orthodox faith. Deneen posits that they are under pressure that makes their exercise of religion in contemporary America incredibly difficult. This pressure, which squeezes anyone who thinks that an “objective good” should trump “individual preference,” is so severe and pervasive in Deneen’s view that he calls it “totalitarian.” Those who question the current political order or its ruling class confront a “new titanic form of power and control” that “will force those who oppose it into submission.”

That “titanic power and control” did not prevent Deneen’s previous book, Why Liberalism Failed, from being published by Yale University Press or from being promoted by former President Barack Obama. Nor did it prevent Regime Change from being published by Penguin Random House, the biggest publisher in the country. Despite the “forced imposition of radical expressivism upon the population by the power elite,” a renegade journalist slipped a Deneen profile past his editors at Politico. But the censors kept it to less than 6,000 words.

Deneen is not the first to say “increasingly unsayable” things in prestige outlets, but he is among the most credentialed. Having passed through Princeton and Georgetown, he has now settled into the David A. Potenziani Memorial College Chair at the University of Notre Dame. Like many political philosophers, Deneen proclaims his dedication to “plumbing our own tradition for resources capable of addressing” problems that contemporary thought cannot resolve.

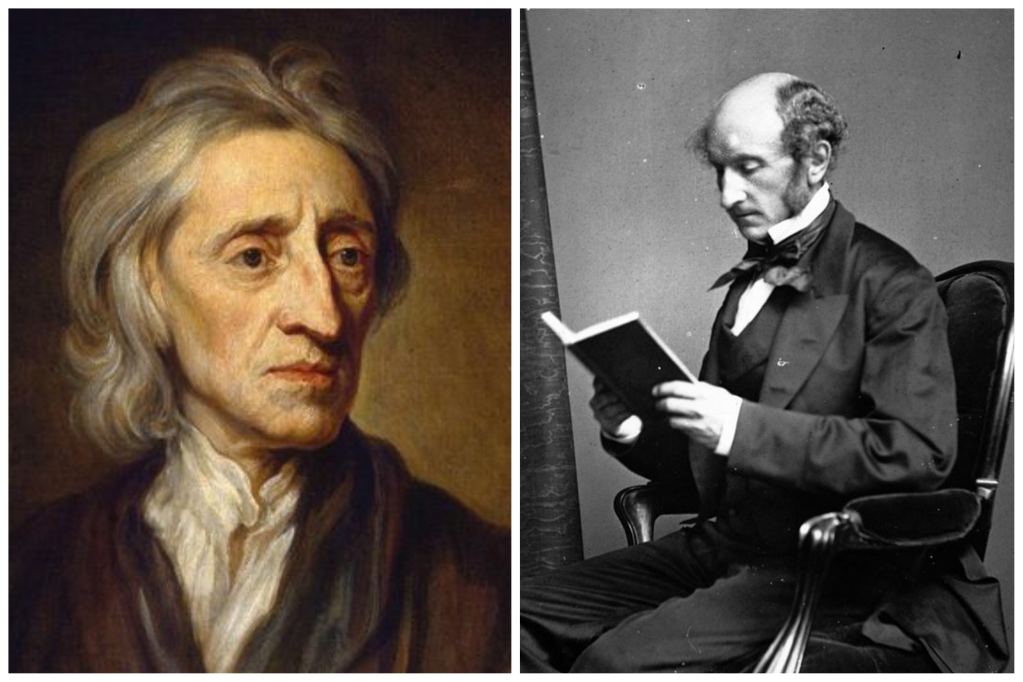

According to Deneen, liberalism—the individual rights philosophy at the heart of the Declaration of Independence—not only displaced the old aristocracy of birth and wealth, but also championed new elites whose claim to rule rested on their ability and will to propel progress. Classical liberals, inspired by the 17th century philosopher John Locke, favor progress through the rational and industrious conquest of nature. Progressive liberals, inspired by the 19th century philosopher John Stuart Mill, favor progress through “experiments in living” which will bring about a beneficial “moral transformation.” Ostensibly opposed, these streams of liberalism flow into one “power elite,” united in its disdain for custom and tradition, which hinder progress, and for the uncredentialed working class, which prefers stability to revolution. This elite uniparty suppresses populist politics and promotes arrangements whereby, in Karl Marx’s terms, “all that is solid”—national boundaries, local community, religion—“melts into air.”

The liberal society, Deneen asserts, works for elites who have the education and resources to thrive. It leaves behind the working class who, as recent populist waves suggest, are recognizing that deaths of despair, vast economic inequalities, and urban decay are the outcomes of self-serving choices by the power elite. That elite, meanwhile, denies its status and asserts, from the cultural heights it commands, that the people are destroying democracy. Deneen observes a “virulent” divide between the “few and the many,” accompanied by calls for civil war and tyranny alike.

Even those who respect the power of old ideas should balk at the suggestion that a two-decades-old rise in deaths of despair, caused mainly by opiates, should be blamed on liberalism, which has been with us for centuries. America was a liberal country in 1910 to 1920, when such deaths dropped steeply, and it was a liberal country from the early 1970s to 2000, when such deaths were flat. Perhaps liberalism’s chickens, released in the 17th century, are coming home to roost right now, and the liberal experiment has run its course. But Deneen doesn’t offer much beyond rhetorical flourishes to show that our present ills are the inevitable result of liberal theory in practice, rather than more recent social, economic, or political trends.

Deneen plumbs modern Western political thought to glean two main ideas. First, liberal thinkers from Locke onward have feared popular outcry. Deneen claims that liberalism “was arguably born … out of a decisive fear and even loathing toward the people.” Second, Deneen thinks that preliberal thinkers like Aristotle offer a better model: a mixed constitution in which the people, with a common sense arising from “everyday interaction with the objects or practices of the world,” check “the overweening ambition of the few.” The elite, conscious of their role and responsibility as a governing class, use their privilege to benefit the people without presuming to subvert their genuine wisdom.

Such a mixed constitution, Deneen argues, requires more mixing between the classes than occurs in contemporary America, and an education that, unlike our own, encourages “serious reflection” on elite responsibilities. Deneen hopes this model can guide our own polity, and that a “self-conscious aristoi” can somehow be pushed into being by popular pressure. Though he concedes that this pressure has so far favored a certain “deeply flawed narcissist,” he insists that an “elite cadre” drawn from today’s governing class will have to take up the burden of “directing and elevating popular resentments.”

Set aside the arrogance of this proposal. As a reading of political philosophy—Deneen’s wheelhouse—Regime Change is deeply flawed. Locke lodged in the people a right to oppose by force rulers who violate their trust, and Mill favored universal suffrage. Yet he casts both as enemies of the people. Meanwhile he treats Aristotle, whose best polity excludes workers of all kinds from citizenship, as a friend of the working class.

This kind of sloppiness matters because Deneen claims that liberalism lacks the resources to deal with today’s conflict between the many and the few, and that premodern thought—suitably modified for our moment—has them. He backs that claim by exaggerating liberal doubts about popular government and premodern confidence in the people’s wisdom. Regime Change is less the promised plumbing of our tradition than a deployment of cherry-picked elements of that tradition to support religious or social conservatism, now drunk on hope. In our political chaos, perhaps anyone can take power.

Among the aims to which such power should be directed, Deneen thinks, is overcoming the “so-called separation of church and state.” After all, opponents of religious establishment, Deneen thinks, are bound to make a “concerted effort to eliminate every last vestige of any claim to objective good,” including an effort to eliminate orthodox religion. But exactly how that separation would be overcome is left mostly to the imagination. And whatever its limits, the separation bears some responsibility for the well-being of institutions like the Young Israel of Staten Island.

Perhaps Deneen is right that orthodox institutions like Young Israel will be better off after a state-assisted “revitalization of a public Christian culture.” Perhaps, appearances notwithstanding, liberalism has been bad for the Jews. But I wouldn’t bet on it.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.