North Carolina and Florida once were key parts of the “Obama Coalition” that spurred new optimism for Democrats following the Bush years. Both have skewed red over the last 15 years, but in this year’s midterms, Democrats got blasted in Florida while putting up a respectable fight in North Carolina.

Why have these two southeastern states taken such different paths?

What Happened in North Carolina

Relative to expectations, November 8 turned out to be a decent night for North Carolina Democrats. Although they lost the vast majority of contested judicial elections in the state, they denied the GOP a veto-proof supermajority by one seat in the state legislature and kept the U.S. Senate race between Rep. Ted Budd and former state Supreme Court justice Cheri Beasley respectably close. Budd ultimately won by less than 4 points. And under the new (court-drawn) redistricting map, Republicans and Democrats split the state’s 14 House seats.

The results follow a trend. After turning blue in 2008 for former Sen. Kay Hagan and Barack Obama, the Old North State has slowly drifted rightward. But it’s a state in which Democrats can still compete—at least when the conditions are favorable.

In a red-leaning state in a red-leaning year, a Democratic flip in North Carolina’s Senate race was always going to be an uphill battle. But at least publicly, Beasley hoped to replicate the model that worked for Hagan and Obama back in 2008: According to a gushing pre-election profile in Rolling Stone, her campaign operated “under the belief that black North Carolinians, who make up a large share of the state’s rural voters, can help her reverse the recent trend against Democrats in this state.”

But that’s not what happened. Instead, Beasley did well in urban and suburban areas with higher concentrations of college-educated white voters while continuing to lose votes in rural areas—even those that have traditionally leaned more Democratic.

Beasley ran up the margins in the counties around the Raleigh and Charlotte metro areas, performing better than past Democratic candidates. And her party saw down-ballot success in those areas too. In the redrawn 13th Congressional District south of Raleigh, Democrat Wiley Nickel upset the Trump-backed Bo Hines, and in the new 14th Congressional District in the Charlotte metro area, Democrat Jeff Jackson won with a comfortable 15-point margin over Republican Pat Harrigan, a fellow millennial veteran.

On the flip side, the rural counties of Anson (west of Charlotte) and Wilson (west of Raleigh) have been carried by Democratic Senate candidates in elections stretching back to at least 2008—until this year, when Budd carried them both.

“It’s hard to outrun realignment,” J. Miles Coleman, associate editor of Sabato’s Crystal Ball, told The Dispatch.

What Happened in Florida

While Democrats’ gains in urban and suburban areas have kept them within striking distance of Republicans in North Carolina, the same can’t be said of Florida, where the sheer scale of Republicans’ wins exceeded expectations.

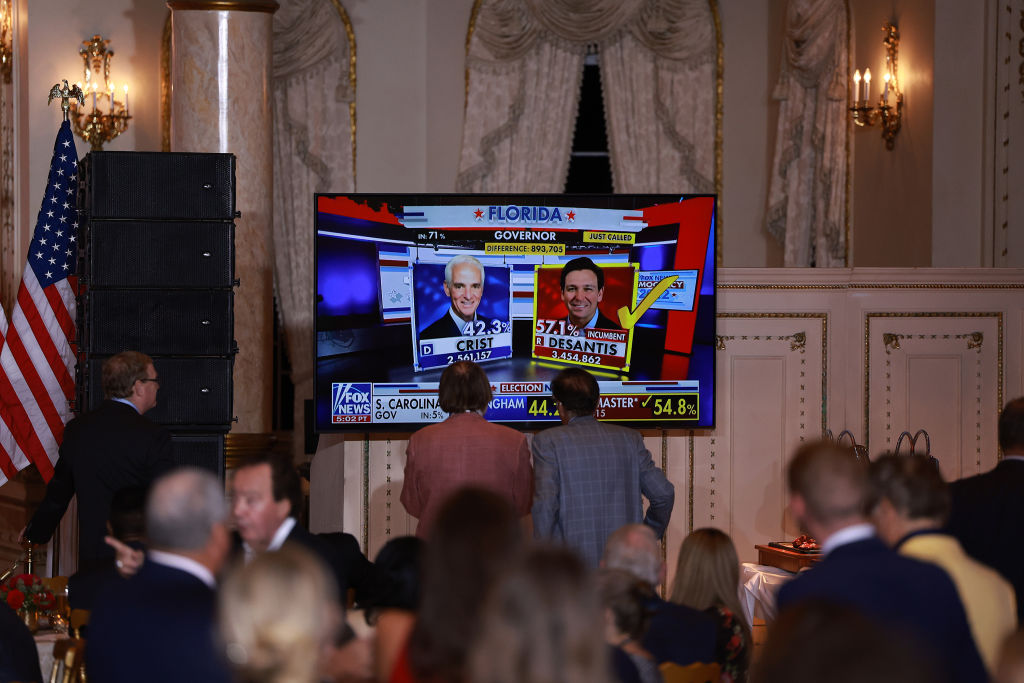

Gov. Ron DeSantis’ 19-point victory over Democrat (and former Republican governor) Charlie Crist and Sen. Marco Rubio’s 16-point win over Rep. Val Demings were among the earliest calls of Election Night, thanks in no small part to the modernization of the state’s electoral system since the Bush v. Gore debacle of 2000.

In 2016, Hillary Clinton carried the majority-Hispanic Miami-Dade County by about 30 points. But in 2022, DeSantis won it by more than 10, turning it red for the first time in 20 years.

It wasn’t just Miami-Dade: Democrats performed poorly basically everywhere.

In 2018, Democratic gubernatorial candidate Andrew Gillum flipped some suburban counties around Orlando and Jacksonville that Trump and Rubio had won in 2016. On Tuesday, DeSantis and Rubio rolled back those gains.

With DeSantis and Rubio at the top of the ticket and the political winds at Republicans’ backs, they didn’t need much help to come out on top. But one Democratic political consultant in Florida told The Dispatch that his party’s losses were compounded by a lack of effort, enthusiasm, and turnout.

“The bottom just fell out,” he said, pointing to the fact that DeSantis netted 500,000 additional votes compared to his 2018 figure—while Crist received almost 1 million fewer votes than Gillum.

That Democratic underperformance had down-ballot consequences. Unlike in North Carolina, Florida Republicans did get over the line to win a supermajority in both houses of the state legislature.

The Democratic consultant said effective Republican gerrymandering was partly to blame for that outcome—but he was also harshly critical of his party’s candidates.

“I should not be able to count on one hand the number of public events that our top-of-the-ticket nominees are doing a day,” he said. “How many events are they doing? Are they doing long hours? I’m not seeing early morning events. I’m not seeing late night events. You know, I’m sure glad our candidates are getting their beauty rest, but that’s not how this is supposed to go.”

Why the Difference?

Analysts point to a few possible causes of the warp-speed transformation in Florida when compared to the slower pace in North Carolina.

Florida Democrats’ lack of effort and organization in getting out the vote could play a part, though North Carolina Democrats have had their own struggles. One pastor who campaigned with Beasley described her political team as “not organized,” and in the closing weeks of the campaign, the state party became embroiled in a conflict with its own (unionized) field staff.

Demographics may also play a role: African Americans—traditionally a reliably Democratic bloc—make up a greater percentage of the population in North Carolina than in Florida, for instance. And as college-educated voters increasingly sort themselves into the Democratic party, North Carolina’s universities may be both attracting and producing a somewhat more educated—and thus Democratic-leaning—electorate.

Age is also an important factor, which benefits Republicans in both states. Older voters turn out at high rates and typically lean Republican, and Florida has a higher percentage of retirees. But North Carolina’s population is getting older, and the GOP has continued to grow its margins in the coastal counties of Brunswick and Pender, which are popular retirement destinations.

“I’ve been saying since the 2020 election that the Democrats in North Carolina are starting to have a Florida problem,” Coleman said.

Nevertheless, while Florida looks set to remain reliably red in the near future, North Carolina Democrats have kept the margins closer, making them—perhaps—a stroke of good fortune away from bucking the state’s recent trends.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.