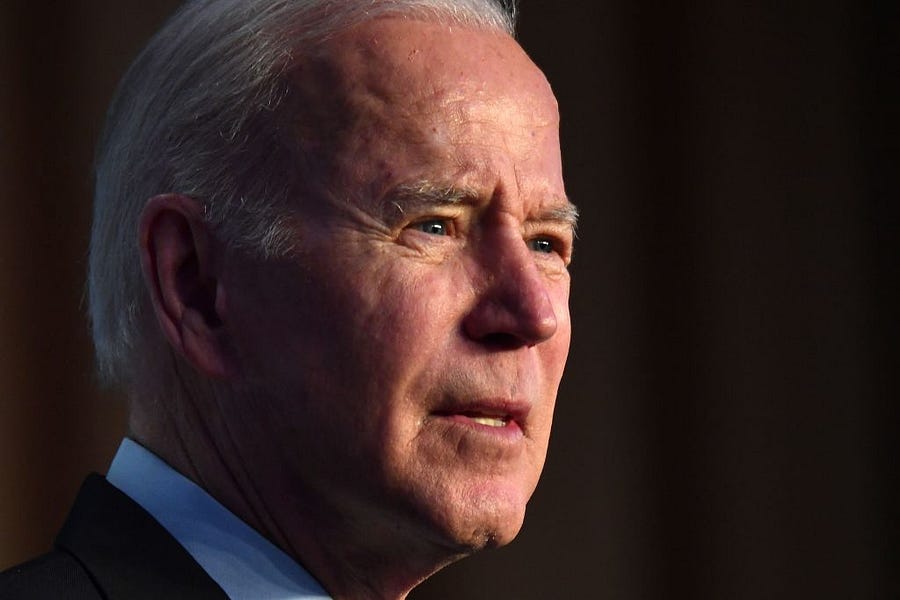

Now less than four months until the midterm elections, President Joe Biden’s historically low approval ratings are ratcheting up political pressures on fellow Democrats, a growing number of whom are voicing their concerns.

According to FiveThirtyEight’s Geoffrey Skelley, Biden’s “approval rating of 39 percent is now the worst of any elected president at this point in his presidency since the end of World War II.” A recent New York Times/Siena College poll had his approval rating among registered voters even lower, at an eye-popping 33 percent.

It’s no wonder then that many Democrats running competitive races this cycle are trying to keep Biden off of their campaign trails. “I really don’t want anyone to join me, like this is my race,” Democratic Rep. Tim Ryan, who is battling Republican J.D. Vance in Ohio’s U.S. Senate contest, said in an interview Tuesday when asked whether he hopes Biden will stump alongside him. “I’m the face of this. It’s my voice, my record, and my issues, so we’re not really asking too many people to come in.”

And if 2022 concerns weren’t enough to put Democrats on edge, the president’s historically low favorability ratings are also spurring speculation about his own political future.

According to that same New York Times/Siena College poll released last week, only 26 percent of Democratic primary voters said they thought the party should renominate Biden in 2024—an astonishing lack of base enthusiasm for a president who appears to be gearing up for a reelection campaign.

“The conversation has started and people are participating in it,” said Democratic Rep. Adam Smith, chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, on the topic of mounting speculation surrounding 2024. Asked point blank whether Biden should be the party’s nominee next cycle, Smith wouldn’t give a clear answer. “I’m trying to get through 2022 at the moment,” he said, pointing out that the midterms are still four months away. “I don’t know yet.”

These political headwinds are now a year in the making. Biden’s approval and disapproval ratings first crisscrossed last August, the same month as his administration’s chaotic withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan. Nearly halfway into his term, Biden continues to poll underwater amid 40-year-high inflation, high gas prices, an ongoing baby formula shortage, and emerging concerns about an imminent recession.

Although some fault the administration’s legislative approach to the economy—even Democratic economists and commentators concede that the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan worsened inflation—much of the intra-party criticism of the White House has revolved around messaging and leadership, not policy.

Biden administration officials met privately with House Democrats last month to brainstorm how the party ought to speak publicly about inflation when confronted with tough questions from constituents and reporters. That closed-door session did little to reassure vulnerable House Democrats. “I just don’t believe that we can try and smooth things over with talking points, as if people don’t know their own lives, their own bills and their own minds,” Democratic Rep. Elissa Slotkin of Michigan told CNN this week.

To swing-district Democrats like Slotkin, any and all White House inflation-related messaging advice seems like a slap in the face roughly one year after Biden reassured Americans that rising prices would be “temporary.” And the fact that both Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell have now admitted they were wrong last year about the path inflation would take has done little to bolster the White House’s credibility on the issue.

“The Biden administration made a terrible misjudgment of downplaying [inflation] at the beginning, and it seemed to show that they really were not on top of their game,” former Democratic Rep. Dan Lipinski said in an interview. “Americans really started feeling the pain of inflation and they felt like the president didn’t understand that, and I think that made it hard to then come back and try to appear to be doing something.”

In other areas, Democrats have held the president to account for issues that are largely beyond the White House’s authority.

In response to the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade, for example, Democratic activists have placed demands on the president that far outstrip his actual policymaking power on abortion. The administration can tinker around the edges, as it did last week when the Department of Health and Human Services clarified guidance around a federal emergency medicine statute.

But on balance there is little Biden can do to counteract a Supreme Court decision beyond pushing Senate Democrats in an evenly split chamber to enact a filibuster carveout and codify Roe v. Wade—a solution centrist Democratic Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona have made clear they won’t support.

“It’s a longstanding practice of Americans to look to the president to make everything better, and that’s not always realistic,” Boston College political scientist Dave Hopkins said in an interview.

That doesn’t sit well with progressives like New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who supported Bernie Sanders in 2020 and who is of the position that Biden is not meeting the moment. “I’m not here to tell the president what to do or what not to do in this respect, these decisions are very personal,” she told The Dispatch when asked whether Biden should be the party’s nominee in the next presidential election. “I do think that in this moment, people want more, and I think that we should do more.”

Instead, progressives are getting less. Democrats’ multi-trillion-dollar domestic agenda package has repeatedly stalled in Congress amid negotiations with Manchin and Sinema—the most conservative Democrats in the Senate. Manchin twisted the knife last week when he torpedoed the climate and tax provisions of the latest attempt to stitch together a package through the reconciliation process.

In some ways, Manchin’s latest blow to Biden’s signature piece of legislation has overtaken the few policy wins Democrats can campaign on—the pandemic relief package, the bipartisan infrastructure bill, and last month’s gun safety bill.

Some Democrats use these legislative wins as a way to redirect questions about Biden’s unpopularity to his predecessor. “I do think that we need to do a much better job of talking about all of the progress that we’ve made with Joe Biden because you had a crazy president before him—why don’t we talk about that?” scoffed Democratic Sen. Mazie Hirono of Hawaii last week. She dismissed increasing voter speculation about Biden’s 2024 prospects out of hand. “I think it’s way too early.”

The fact that there is an ongoing chatter about whether Biden should run for reelection does nothing to clarify who might emerge as his successor. Vice President Kamala Harris is also unpopular, and no other prominent Democrat has emerged as an obvious alternative.

There’s also the concern that Biden is the only Democratic candidate who can beat Trump should he also decide to run again in 2024. Speaking with reporters last week, House Progressive Caucus Chair Pramila Jayapal pointed to recent polling that shows voters still prefer Biden to Trump in a head-to-head matchup. But even she conceded that heading into 2022, her party leader’s low favorability among voters is a major obstacle.

“I’m not trying to sugarcoat it,” Jayapal told reporters last week. “It doesn’t help us that there’s—the president’s poll ratings are low.”

Biden’s age is another concern. Should he follow through with his stated intent to run for reelection, he will be 82 years old when Election Day rolls around.

“[There] is a great concern that a lot of Democrats have that he cannot go into this next election looking like he is not a good leader, and certainly age is a part of that,” Lipinski, a former member of the centrist House Blue Dog Coalition, said in an interview. “I think there’s a less than 50/50 chance that he runs again. He certainly can’t admit that, because that would hurt him even more.”

Most rank-and-file Democrats are keenly aware of this dynamic, and simply shrug their shoulders when pressed on the matter in interviews.

“There’s nothing to do about it. There’s all kinds of headlines I would prefer not to not have to see,” said Democratic Sen. John Hickenlooper of Colorado, who briefly sought the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination in 2020. “Of headlines I’m not crazy about, that’s pretty far down the list.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.