Republican office-seekers in recent years have seen the abortion issue as a bag of bricks—a burden that makes it all but impossible to win the race.

Where are we, really, on abortion? Where should we be?

Three main points to start from:

One, the pro-life movement will not have won when nobody can get an abortion—the pro-life movement will have won when nobody wants an abortion. In this, there is a fundamental asymmetry between the pro-life and pro-choice movements. For the pro-life movement, the regulation of abortion is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the desired outcome. The regulation or prohibition of abortion will have the practical effect of preventing some abortions, and it will have the salubrious secondary effect of encouraging Americans to disentangle themselves, mentally and politically, from the practice of abortion.

Our pro-choice friends bristle when the pro-life movement compares its project to the effort to abolish slavery (there are obvious differences, of course, but also important similarities, the most important being that both questions are rooted in a fundamental disagreement about who is a whole human person and who is not), but I hope they will indulge the following hypothetical: If the normal course of economic and social development had led to the gradual and largely voluntary eradication of slavery in the United States, wouldn’t we still want a law prohibiting it, even if the question were moot? Wouldn’t we still want to cultivate anti-slavery sentiment? To repent of the wrongs that were done under slavery and to mourn its horrifying human price? I think so. I am less sure that this necessarily is the case for abortion. For me, it is more important that the killing should stop than that pro-lifers should have some kind of political “victory” that results in a de jure prohibition of the abortion while de facto leaving the practice itself largely in place.

The second basic point: The Dobbs decision is not the kind of hollow victory referenced immediately above. For one thing, Dobbs does not prohibit abortion—it only opens political space for democratic action to restrict abortion rights or codify abortion rights. Very likely, it will continue to do what it already has done: enable democratic action leading to radically different outcomes in places with radically different political characters. A pro-lifer may not like an abortion carried out in Connecticut any better than one carried out in Oklahoma, but that does not detract from the value of Dobbs, the desired outcome of which was only to allow the kinds of democratic contests in which pro-lifers currently are engaged—and, it bears noting, mostly losing at this time.

The path forward is one of ordinary politics and persuasion—and the persuasion ultimately is going to be more important than any individual political contest. With that stipulation, the Dobbs regime could represent an enduring settlement on abortion—a modus vivendi, if we will allow the term—at the federal level: That matter has been returned to the state legislatures and, as far as the federal government need be concerned, that is that. Neither the most strident pro-life advocates nor their opposite numbers on the pro-choice side are much inclined to accept Dobbs, which in effect holds that the only national policy on abortion is that the people are free to settle the question themselves, democratically, on a state-by-state basis. The fact that the most insistent activists on either side both have serious complaints about Dobbs is one indicator that it probably is the right settlement, at least at the national level. Abortion will be difficult to work through at the state level, too, of course, because it is an issue of competing libertarian interests: For the pro-choice camp, it is a matter of a woman’s autonomy over her own body; for the pro-life camp, which understands the pro-choice position as begging the question, it is an issue of the rights of the other body involved. It is not necessary for us—Americans on either side—to agree with the other side’s position, but if you cannot understand it or cannot understand how it possibly could be held in good faith, then you are suffering from a lack of civic and moral imagination that contributes only to fanaticism and ill-will rather than to understanding and the project of necessary persuasion.

And the third point from which to start: Accepting Dobbs as the long-term compromise at the federal level is desirable and necessary for reasons unrelated to the abortion issue itself. My own belief—as a pro-lifer and a conservative who also cares a great deal about the rest of the conservative agenda—is that the Republican Party is a lost cause. Right-wing populists–the people who now dominate the GOP–ultimately have no enduring interests beyond symbolic culture war skirmishing and maintaining long-term welfare benefits and other economic subsidies important to white people (SNAP and other programs associated rightly or wrongly with nonwhite urbanites will be on the chopping block, while Social Security and Medicare must be held sacrosanct and corporate welfare remains popular). A new center-right coalition will have to be forged, and a party organized to support it, if conservative policies are to be advanced by democratic and legislative means. The Republican Party is no longer available, in a practical sense, as a vehicle for those purposes.

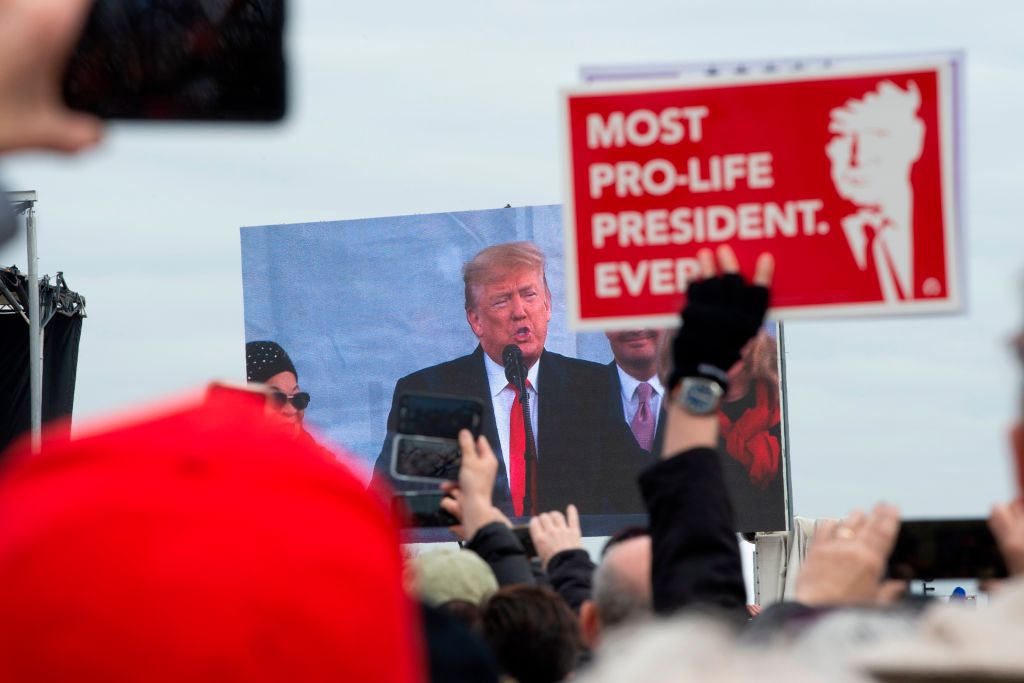

Keeping the abortion issue urgently relevant as an issue in federal policymaking will make creating such a forward-looking coalition very difficult, if not effectively impossible. And there are elements on both sides that will labor to keep the issue alive federally both as a matter of genuinely held conviction and out of rank self-interest. I do not think the pro-life movement in institutional form is going to be much of an ally moving forward on non-abortion issues. At this point, leaving the organized pro-life movement behind seems to me to be a very, very small price for full-spectrum conservatives to pay: Organized pro-lifers, along with white evangelical Christians at large, have hitched their wagon politically to Donald Trump, his movement, and his party—never mind that Trump opposes most of the pro-life agenda, that he thinks the Dobbs decision was a mistake even as he selectively takes credit for appointing the Supreme Court justices who voted for it. (The author of Dobbs, Justice Samuel Alito, was appointed by George W. Bush.) In fact, the white evangelicals steeped in nationalism-populism who make up the bedrock of the Trump movement almost certainly will be a major impediment to advancing conservative policies through the legislative and democratic processes, for several reasons. For starters, they simply do not favor policies that would reform the entitlement system and the tax code, liberalize trade, or support higher education and scientific research. They also put a low priority on or oppose doing the necessary things to secure U.S. interests such as supporting Ukraine’s self-defense against the Russian invasion, and, in other cases, they may sympathize with certain policy goals but decline to act on these when doing so means cooperation and compromise with Democrats and others perceived as culture war enemies.

We have little reason to think the people who dominate the pro-life movement today would be, on balance, any help in the project of, say, negotiating a free-trade pact between the United States and the European Union, which is at the top of no one’s agenda at the moment but should be. (Accounting for services and investment, the European Union is by far our largest trading partner, though China looms larger on the narrower issue of trade in goods.) The so-called conservatives in the Trump movement are, in fact, the most politically relevant impediment to such projects (see the sorry history of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership), more significant even than the anti-trade elements in the Democratic-leaning industrial unions.

So, if Dobbs settles the abortion issue at the national level, then it is difficult for me to see anything in the political math other than the conclusion that continuing to organize conservative politics around the people who are going to nominate Donald Trump in 2024 is a net loser.

A minority of Americans have a positive view of Trump and Trumpism, while a majority of Americans take a dim view of Trump and his movement. Trump is up a little in the polls at the moment, but, historically, the figures have been roughly one in three for Trump and two in three against. Conservatives who have convinced themselves that they cannot win without the Trump element are thinking small and short-term—no surprise, given that these people mostly are Republicans, after all. The weird thing is that polls indicate broad support for better, more conservative policy in more than a few important cases—and, in many cases such as that of Ukraine, that is especially true among people who are not Republicans. Consider this as a pragmatic, non-normative question: If you care a great deal about U.S. support for Ukraine, why would you join your interests to the Republican Party, members of which disproportionately oppose your agenda? If you care about trade, why make yourself a hostage of the party that is relatively hostile to trade? If you want to build a political coalition open to non-white people, why link up with the people hooting at “Nimbra Randhawa”?

I myself do not care very much whether the next president is Nikki Haley, Joe Biden, or Mickey Mouse—I care that the budget gets nudged toward balance, that the economy is allowed to thrive, that Vladimir Putin loses, badly, in Ukraine. If conservatives cannot find enough allies in two-thirds of the population to overcome the opposition of one-third of the population, then what exactly is it we think we are doing? Lately, Democratic Sen. John Fetterman has taken a more sensible posture on foreign policy than most leading Republicans—surely if the limits of our potential coalition are Sen. Fetterman on the left and John Bolton or Nikki Haley or the editors of The Dispatch on the right, then our potential coalition is big enough. Take “YES” for an answer.

For conservatives in 2024, the Republican Party is a bag of bricks—and all they have to do is put it down.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.