When Americans go to the polls every other November, they’re ostensibly voting on dozens of different policy priorities, electing public officials that will make hundreds—if not thousands—of decisions on their behalf in the coming years. But political campaigns (and the outlets that cover them) only have the bandwidth to emphasize a handful of these issues in any given year, particularly during midterm elections.

In 2010, Republicans reclaimed control of the House of Representatives running primarily on a platform of cutting federal spending; Democrats retook the House eight years later pledging to protect the Affordable Care Act.

It’s still early in the 2022 cycle, and officials in both parties are still honing the messages that will determine whether Democrats’ incredibly narrow congressional majorities hold. But Republicans seem to be circling in on a theme they sense could be an electoral winner: cancel culture.

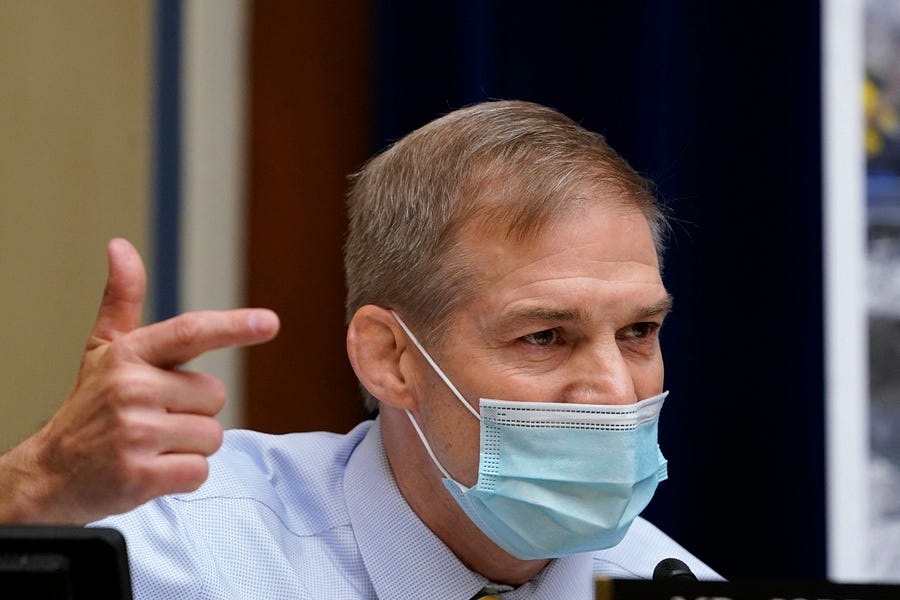

It’s an ambiguous term; one that has come to serve as a catch-all phrase describing a wide assortment of perceived progressive overreach. “It’s sort of like the old Supreme Court line,” Rep. Jim Jordan told The Dispatch when asked how he defines the phenomenon. “You know it when you see it.”

And Republicans have been seeing a lot of it lately.

A Virginia police officer being fired after anonymously donating $25 to the legal defense of Kyle Rittenhouse, the teenager charged with homicide for shooting protesters during the riots in Kenosha, Wisconsin, last fall? Cancel culture.

Dr. Seuss Enterprises ceasing publication of six titles because they “portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong?” Cancel culture.

Disney removing actress Gina Carano from The Mandalorian after she compared being a Republican today to being a Jew in Nazi Germany? Cancel culture.

Sen. Josh Hawley losing his book deal and Rep. Elise Stefanik losing her Harvard Institute of Politics board seat after objecting to the election results on January 6? Cancel culture and cancel culture.

Major League Baseball (MLB) relocating this year’s All Star Game from Atlanta after top Democrats hyperbolically compared Georgia Republicans’ new election law to Jim Crow? Cancel culture.

Voting to impeach the former president on charges he incited an insurrection? “Constitutional cancel culture.”

This sense of alienation from mainstream society is not new for Republicans. Whether it’s labeled “cancel culture,” or “wokeness,” or “political correctness,” or “censorship,” the feelings the phrases are meant to evoke have been around for decades. But Jordan believes that whatever it’s called, it’s worse now than it’s ever been.

“It’s a direct attack on liberty; it’s just a direct threat to our freedoms as Americans,” the Ohio Republican said in an interview last month. “That’s why I speak out against it. … I don’t know if it helps us or hurts us [politically], but that’s not my motivation. My motivation is I just think it’s wrong.”

Others in the GOP are more upfront about the electoral implications. “Cancel as many people as you can right now,” Sen. Rick Scott—chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee (NRSC) this cycle—wrote in an open letter to “Woke Corporate America” a few weeks back. “There is a massive backlash coming. You will rue the day when it hits you. That day is November 8, 2022. That is the day Republicans will take back the Senate and the House. It will be a day of reckoning.”

Rep. Tom Emmer, chairman of the National Republican Congressional Committee (NRCC), echoed those sentiments in a statement provided to The Dispatch. “There is a backlash brewing against corporations doing the bidding of far-left actors,” he said. “It puts Democrats in a very difficult spot.”

It’s not just Republicans saying this; some Democrats more or less agree with the assessment. “Wokeness is a problem and everyone knows it,” veteran Democratic strategist James Carville told Vox last week. “Large parts of the country view [Democrats] as an urban, coastal, arrogant party, and a lot gets passed through that filter. That’s a real thing. I don’t give a damn what anyone thinks about it—it’s a real phenomenon, and it’s damaging to the party brand.”

Public opinion analyst Harry Enten deemed criticism of cancel culture one of the GOP’s “best political plays” because polling shows it’s bipartisan. “Fear of cancel culture and political correctness isn’t something that just animates the GOP’s base,” he wrote. “It’s the rare issue that does so without alienating voters in the middle.” A late-February Harvard/Harris survey found 64 percent of registered voters believe there to be “a growing cancel culture” that is “a threat to our freedom.”

Aside from standing up to Democrats and supporting former President Trump’s America First agenda, a February survey from GOP polling firm Echelon Insights found being “outspoken against woke, progressive ideology and cancel culture” one of Republican voters’ top “must-have” characteristics in a GOP primary election. (Disclosure: The author interned at Echelon Insights in 2015.)

“What we don’t know,” Echelon Insights co-founder Kristen Soltis Anderson told The Dispatch, “is what word in that statement is doing the most work. Is it outspoken? Is it woke? Is it progressive? Is it cancel culture? My suspicion … is that ‘cancel culture’ itself is not the driver, but perhaps outspokenness against woke ideology.”

Regardless of the exact terminology, GOP campaigns are taking notice. Kelvin King—the owner of a construction company in Atlanta—launched his U.S. Senate bid against Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock in early April pledging to fight back against “woke corporations” and “the cancel culture.” Days later, Josh Mandel—a candidate for retiring Sen. Rob Portman’s U.S. Senate seat in Ohio—published an op-ed in the Toledo Blade entitled, “We must combat cancel culture.”

But Republicans are struggling to coalesce around what “combating cancel culture” would actually look like in practice, with some advocating for a dramatic departure from limited-government conservatism while others argue political correctness is a cultural issue, not a public policy one.

In the wake of the corporate backlash to Georgia’s election law, Trump suggested that Republicans take a page out of the Democrats’ playbook. “For years the Radical Left Democrats have played dirty by boycotting products when anything from that company is done or stated in any way that offends them,” he wrote in a statement. “Now they are going big time with WOKE CANCEL CULTURE and our sacred elections. It is finally time for Republicans and Conservatives to fight back—we have more people than they do—by far! Boycott Major League Baseball, Coca-Cola, Delta Airlines, JPMorgan Chase, ViacomCBS, Citigroup, Cisco, UPS, and Merck. Don’t go back to their products until they relent. We can play the game better than them.”

J.D. Vance—the author and venture capitalist who is likely to join Mandel in Ohio’s U.S. Senate race in the coming weeks—took this sentiment a step further last month when he urged Republicans to retaliate against businesses whose leaders met to coordinate responses to Republican-led efforts to change voting laws in states across the country. “Raise their taxes and do whatever else is necessary to fight these goons. We can have an American Republic or a global oligarchy, and it’s time for choosing,” said Vance, who declined to be interviewed for this story. “At this very moment there are companies (big and small) paying good wages to American workers, investing in their communities, and making it easier for American families. Cut their taxes. No more subsidies to the anti-American business class.”

Rep. Peter Meijer, a freshman Republican from Michigan, grew animated when presented with Vance’s comments. “How is that conservative? Where is there a fidelity to an underlying set of beliefs or principles other than just taking cues from the left and being inherently reactive?” he scoffed. “If you’re using the government to compel something you like, you’re setting the precedent for the government to be compelling something you don’t like. And the non-hypocritical approach is to just not have the government be a coercive entity towards those ends.”

Mandel also dismissed Vance’s approach, saying it sounded like “a big government liberal solution—not a conservative one.” His plan of attack? Repeal Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. The move would eliminate liability protections for online technology platforms that Mandel believes unfairly censor conservative voices, and, ironically, almost assuredly lead those platforms to dramatically reduce the total amount of speech they allow on their sites. “As a United States Senator, it will be a top priority of mine to work with other constitutional conservatives to be the worst nightmare for the deadwood media and these Big Tech companies,” Mandel said.

The phenomenon is a political goldmine: Real enough to generate clicks, campaign contributions, and votes; ephemeral enough to lack a clear-cut legislative fix. Perhaps realizing this, endeavoring Republicans have found increasingly creative—yet low stakes—ways to get involved in the debate and portray themselves as fighting back.

Gov. Ron DeSantis, for example, pledged in March that Florida’s public school curriculum would “expressly exclude unsanctioned narratives like critical race theory.” Sen. Marco Rubio threw his weight behind a recent unionization effort at Amazon—not because he is pro-Big Labor, but because “companies like Amazon have been allies of the left in the culture war.” Sen. Ted Cruz, in an op-ed last week, swore off any further political contributions from corporate PACs that have “smear[ed] Republicans without paying any price.” The latter two—plus Sens. Mike Lee, Josh Hawley, and Marsha Blackburn—symbolically got back at Major League Baseball by introducing legislation to revoke the league’s antitrust exemption. “For decades, the MLB has been given a sweetheart deal by Washington politicians,” Hawley said. “But if they’d prefer to be partisan political activists instead, maybe it’s time to rethink that.”

Rep. Adam Kinzinger—an Illinois Republican—thinks some of his colleagues are getting caught up in the moment. “Emotionally, we would love to be able to fire back at stupid decisions like overreactions of corporations,” he said in an interview. “But I think if you get back to the very basics of what we as Republicans believe, we believe that private companies can make decisions, and the government can deal with that, and that consumers can make decisions as well.”

“I totally disagree with MLB’s decision,” he added. “But if we’re going to now alter the entire course of public policy based on a decision a corporation made, I mean, basically what you’re in essence trying to do then is set up a de facto command economy whereby the government and its values—or the values of those in the government now—determine the business decisions of a business. … I just think everybody needs to take a deep breath and realize what kind of a country we want to be, and if we really want to just get into where every issue is power politics and whoever has the power at the moment.”

But that deep breath probably isn’t coming anytime soon—there’s an overwhelming energy on the right these days in favor of using whatever governmental tool is in hand against progressives’ cultural hegemony. “God forbid we do something,” Vance responded when informed his proposal was likely unconstitutional.

Meijer agreed that Republicans have work to do on this issue, but not necessarily in statehouses or the Capitol. “The Overton window has kind of shifted to where the narrative that ‘Republicans are evil’ is not just unquestioned in many elements on the left, but in corporate America, too. And to me the broader challenge is how do we regain that credibility,” he said. “We’ve lost some credibility to be viewed as serious participants in larger cultural clashes. And if all we’re doing is talking to a Newsmax and OANN crowd, we’re not flexing those persuasive muscles to be able to win over voters in the center.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.