Mitra Aliabouzar has plenty of bad memories from her time in Iran’s Evin prison: hours-long interrogations; no contact with family, who for weeks didn’t know whether she was alive; and 39 days of solitary confinement in a cell scarcely large enough to stretch her legs.

But the painful memory that stands out “clearly and visibly” more than a decade later is saying goodbye to her cellmates, Baha’i activists Fariba Kamalabadi and Mahvash Sabet. Both at the time were four years into 10-year sentences.

“I had 30 minutes to pack and I just spent the whole 30 minutes in Fariba’s arms. I didn’t want to leave,” Aliabouzar said in an interview with The Dispatch. “I left my other family back in prison.”

Kamalabadi and Sabet—a psychologist and a poet, both grandmothers—now face another decade behind bars for their political and spiritual leadership in the Baha’i community. The two women have become the public faces of the regime’s persecution of the religious minority group, serving as a source of inspiration to all Iranians fighting for freedom from the Islamic Republic’s repressive rule.

Just a few years after Kamalabadi and Sabet regained their freedom, Iranian officials last month sentenced them to another 10 years in prison. The judge presiding over their brief trial chastised the defendants for “not having learned their lesson”—that is, to stop speaking out on behalf of their long-persecuted faith—the first time around.

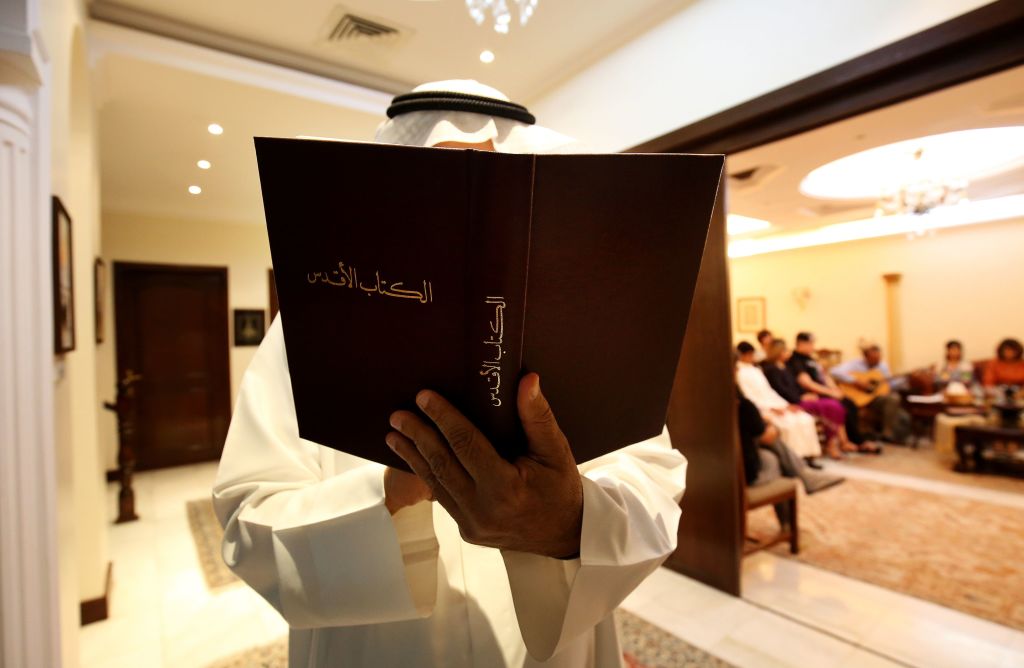

As Iran’s largest non-Muslim religious minority, Baha’is have suffered more than four decades of arbitrary detention, forced evictions, home raids, torture, and execution at the hands of the Islamic Republic. The clerical regime doesn’t formally recognize the faith, dismissing it as a political rather than spiritual movement. Hundreds of Baha’is have been killed, and many more have been imprisoned, in the last four decades, according to Amnesty International.

Baha’i activists say that persecution has intensified in recent months. The government has reportedly arrested dozens of Baha’is since July as security forces crackdown on Iranians from all walks of life for protesting the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini in police custody.

“What we see in Iran today is the extension of this persecution to the generality of Iranians,” Simin Fahandej, representative of the Baha’i International Community to the United Nations, said during a Human Rights Council special session on human rights violations in Iran last month. “A government that oppresses one group will surely be unjust to all groups in the long-run.”

Indeed, the Islamic Republic recycles many of its attacks against Iran’s some 300,000 Baha’is to undermine the legitimacy of ongoing protests, which many participants say are more aptly described as an uprising. Regime officials have long charged Baha’is with spying for Israel because of their headquarters in Haifa—an allegation Baha’is reject as pretense for further repression. The regime now claims that the current wave of civil unrest is being directed by covert Israeli and American operatives. Tehran has even singled out Baha’is (and their alleged foreign backers) as the driving force behind the demonstrations, accusing the religious minorities of sedition and sabotage.

“The Baha’i spy service, following the orders of the Baha’i headquarters in the occupied city of Haifa, played a major role in the scenes of unrest and sedition and the encouragement to destroy public property,” Iran’s Intelligence Ministry said in a September statement.

As Iranian jail cells fill with political prisoners, protesters and Baha’i activists are sure to come into close contact. For Aliabouzar—an agnostic who met Kamalabadi and Sabet while in prison for organizing protests during the 2009 Green Movement—such encounters with the Baha’i faith and its adherents proved life-altering.

Sabet, a former educator, wrote a volume of poems about her experience in Evin that later won international literary awards. And Kamalabadi, a trained psychologist, offered a sympathetic ear to inmates as the ward’s de facto counselor.

Every day at 7 p.m., Aliabouzar would get together with Kamalabadi to teach her English. The two women quickly forged a close friendship. “That was my favorite time of the day. We bonded so strongly,” Aliabouzar recalled. “She’s a symbol of strength and courage for me.”

“In one of my conversations with my interrogator, I told him that I felt thankful for being arrested because otherwise I would not have met these incredibly selfless people like Fariba and Mahvash,” Aliabouzar added. “They never said anything about the details of what they went through. They always said the hardest part for them was not knowing what was happening to the Baha’i community.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.