When it comes to putting the January 6 siege of the Capitol in perspective for the upcoming Senate trial of Donald Trump, the 80-page brief filed by the House impeachment managers is thorough, as are two are two shorter, academic essays–Yale historian Timothy Snyder’s “The American Abyss,” and foreign-policy expert Mark Danner’s “Be Ready to Fight.”

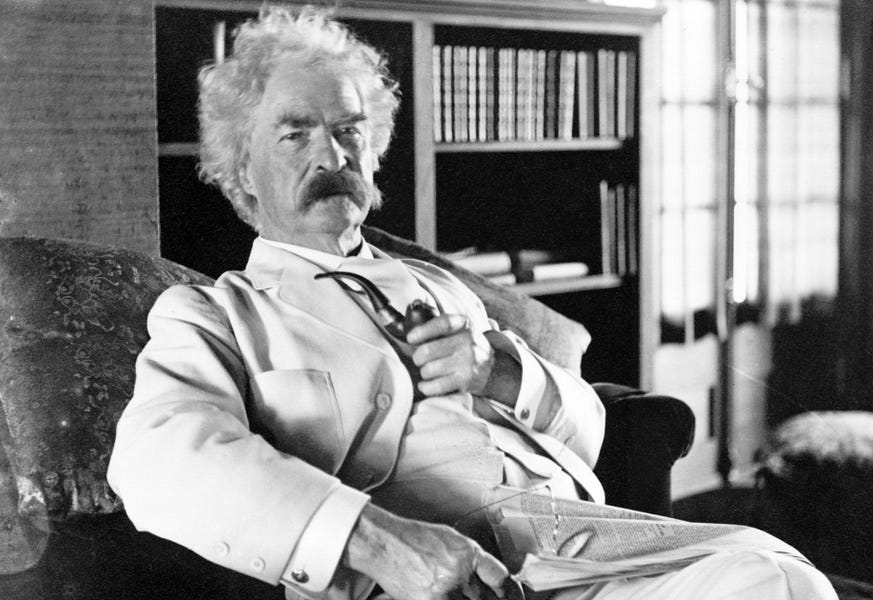

There is, however, another writer who should be read as the Senate trial begins: Mark Twain. Twain never imagined the Capitol being trashed by an angry mob, but in his 1901 essay, “The United States of Lyncherdom,” he foresaw how a mob, like the ones he knew as a Southerner, could terrorize a major, northern city. For Twain, the mob was a staple of American life, not an anomaly, and in “The United States of Lyncherdom” he treated the mob as a political force to be reckoned with.

“I may live to see a negro burned in Union Square , New York, with fifty thousand people present, and not a sheriff visible, not a governor, not a constable, not a clergyman, not a law-and-order representative of any sort,” Twain wrote.

Twain was responding to the rise of lynching, the increased influence of the Ku Klux Klan, and the Supreme Court’s landmark 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision that made “separate but equal” the law of the land. But Twain’s essay, written, as he tells readers, in the wake of an incident in Missouri in which a mob lynched three black men and burned the houses of five black families after a white woman was found murdered, goes far beyond the Jim Crow era in which he lived.

It is a short step from Twain imagining a Union Square mob 120 years ago to the present moment when a Confederate flag and a makeshift gallows with a noose were part of the siege on the Capitol. We need only change New York to Washington, D.C., Union Square to the Capitol, and the absence of police in Union Square to the weak police presence at the Capitol to see how “The United States of Lyncherdom” puts our own situation under a historical magnifying glass.

Central to Twain’s portrait of a mob is his idea that the members of a mob constantly worry about being considered unsupportive of the mob’s values and its leaders. They fear, in Twain’s words, being “offensively commented upon.” It is harder to think of a better description of how and why President Trump exercised such influence over the Capitol Hill mob.

In the wake of the attack on the Capitol, several administration officials resigned: Mick Mulvaney, Secretary of Education Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, and Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao. Yet in the weeks between the election and January 6, Trump’s Cabinet, along with Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, remained silent while the president complained about a rigged election.

Trump’s supporters, anxious to avoid getting on his wrong side, refused to contradict him when he spread conspiracy theories. Trump saw their silence as a green light to do as he wished. Only after he began to confront the backlash against the Capitol mob and to fear the personal consequences of being associated with its violence did the president start to talk about a peaceful handover of power to the Biden administration.

When Twain thought about the best way to curtail the power of mobs, he drew hope from the tendency of a mob to back down when someone with courage defied it.“For no mob has any sand in the presence of a man known to be splendidly brave,” Twain declared in his essay.

In Huckleberry Finn Twain had a single figure, Colonel Sherburn, face down a mob targeting him. Sherburn declares, ”the pitifulest thing out is a mob,” before he vanishes from Huckleberry Finn, having made Twain’s point for him. In “The United States of Lyncherdom” no Colonel Sherburn appears, but more than a decade afterHuckleberry Finn, Twain remained convinced that mobs can be defused if “morally brave men” confront them.

In emphasizing the importance of character rather than structural change as the antidote to mobs, Twain was being distinctly old-fashioned. He acknowledged the shaky ground on which he stood when he called for morally brave men to come forward. “Where shall these brave men be found?” he asked, worried that there were not enough of such men to go around. There is no ignoring Twain’s doubts, but even harder is imagining we can get by today without posing his bravery question.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of literature at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Winning the Peace: The Marshall Plan and America’s Coming of Age as a Superpower.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.