The list of super PACs supporting President Donald Trump in 2020 reads like verbal Sudoku: There’s Great America, Make America Great Again, Americans for Greatness, the Committee to Restore America’s Greatness, Make America Number 1, and America is Winning Again. So much greatness.

But one group stands out in both its mission and its fundraising prowess. That group is Black Americans to Re-Elect the President, which has raised nearly $2.8 million since it began accepting contributions in May 2018. According to OpenSecrets.org, Black Americans to Re-Elect the President has raised more more money during the 2020 presidential cycle than any other pro-Trump SuperPAC other than America First Action, Trump’s “official” super PAC, which has raised $46 million.

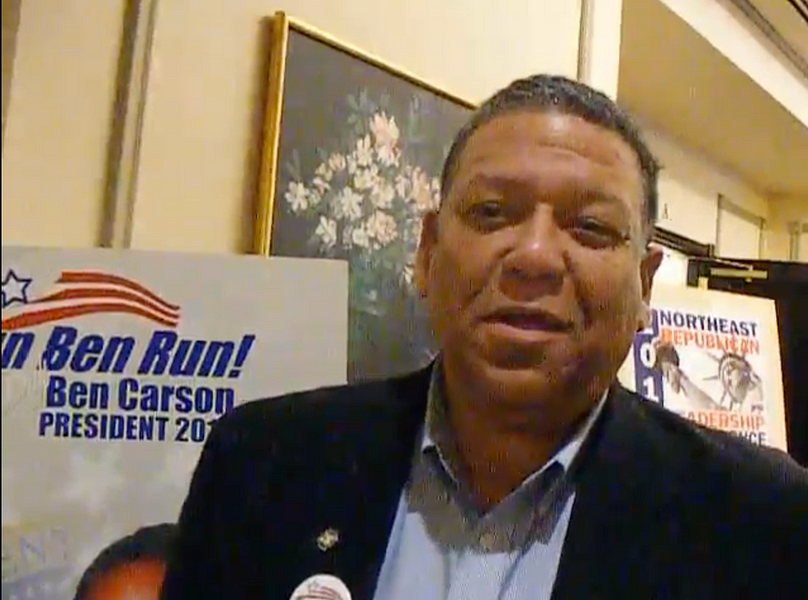

The mastermind behind the group is Vernon Robinson, a pugnacious controversialist and serial fundraiser who once dubbed himself the “Black Jesse Helms.” Robinson, 65, a graduate of the Air Force Academy and former officer, has spent years in North Carolina running dozens of (mostly) unsuccessful campaigns for local and national office.

Robinson’s most controversial campaign took place in 2006, where the incendiary accusations he leveled against his opponent were similar in tone, if not exactly the same in content, as something ripped from the Trump playbook.

At the time, he relentlessly accused his opponent, North Carolina Democratic Rep. Brad Miller of being gay. “If Miller had his way, America would be nothing but one big fiesta for illegal aliens and homosexuals,” a Robinson radio ad said.

In one flyer, Robinson emphasized Miller was “childless” and had “gotten into bed” with a male blogger from San Francisco. (Miller had contributed to the Daily Kos, run by Markos Moulitsas.)

Unbeknown to the public, Miller and his wife, Esther Hall, were unable to have children because she had a hysterectomy 20 years prior.

“To be clear, the gay stuff didn’t bother me even then,” Miller told me. “I was inclined to make a joke of it and say that it was true that I kind of liked show tunes but otherwise I was straight, but my consultants said I had to be outraged.”

“Many of his attacks had some weird sexual insinuation,” said Miller. “He ran an ad that I voted to study masturbation by old men and sexual stimulation in teenage girls because I voted for the NIH budget. NIH spends a good deal more to study cancer and heart disease.”

Robinson told me he never called Miller gay. He said he simply used the term “political bedfellows” and “that was the case.”

“The left is going to lie, like they always do,” he said.

Miller beat Robinson by a nearly 2-to-1 margin.

But Robinson’s attacks have often been aimed at Republicans whom he deemed insufficiently conservative. In a 2004 congressional primary, Robinson compared his opponent, conservative Republican Virginia Foxx, to then-Sen. Hillary Clinton, attempting to portray her as a left-wing feminist. (During the campaign, Robinson was condemned by Jack Kemp but praised by Pat Buchanan.)

Robinson called Foxx a “political cross-dresser” who accepted money from “radical homosexuals.”

That specific race featured a Robinson campaign ad that eerily intoned, “The aliens are here, but they didn’t come in a spaceship. …They sponge off the American taxpayers. …They’ve even taken over the DMV. These aliens commit heinous crimes.”

And In one 1997 city council race, Robinson accused his Republican opponent of being a nudist. (“Yep – like nekkid – like no clothes,” read one campaign mailing.)

Despite his often unseemly tactics, Robinson hasn’t lost all his campaigns. He won a seat on the Winston-Salem city council, but lost his re-election bid in 2005 after he paid $2,000 for a one-ton monument of the Ten Commandments to be moved to the steps in front of City Hall. That very day, the mayor forced city workers to remove it.

Robinson said the Ten Commandments stunt was inspired by Judge Roy Moore in Alabama, writing that more religion was needed in public spaces to keep the left from overturning the Boy Scouts’ policy of “keeping atheist pedophiles out of pup tents with our 13-year-old sons.”

And that thing about America becoming a “fiesta for immigrants and homosexuals”?

“It has become that,” Robinson told me.

Now Robinson is betting that his confrontational style will win Trump more black voters, hoping anti-immigrant and anti-gay sentiment will shift African Americans toward the president. He is buoyed by his preternatural ability to raise campaign money: Since 2004, he has set up a total of five campaign committees and super PACs, raising more than $26 million for himself and other candidates.

His messaging relies heavily on the notion that Democrats have failed black voters. He frequently cites problems in inner cities that have long been run by Democrats and tries to convince African Americans that Democrats are the real racists.

“Antifa—or KLANtifa, as I call them—is the modern face of the Democratic Party,” Robinson tells me in one of his extended monologues during our discussion. “It is easier to survive a nuclear bomb than it is to survive 70 years of Democrats running your city into the ground,” says Robinson. (The internet meme he mentions with this fact actually cites Hiroshima, and its veracity is in question.)

Robinson believes with his help, Trump will get more than 20 percent of the African American vote in November of this year—two and a half times greater than the 8 percent Trump received in 2016. He argues Democrats are creating “faux racial crises” to try to gin up turnout, calling it “despicable politics.”

“Most people believe the Democratic Party is strong in the black community,” Robinson tells me, adding he thinks Democrats have a “significant and exploitable strategic weakness, to have to have a high turnout and 90 percent of the [black] vote in order to win.”

In 2018, he began testing his theory. He used $4,400 to purchase an ad on black radio in Little Rock, Arkansas, that warned the city’s black residents that “white Democrats will be lynching black folk again” if they regained control of the House of Representatives.

The ad, which ran as the U.S. Senate debated Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court, featured two African American women discussing the committee’s actions. In the script, one woman muses that if Democrats can bring “a presumption of guilt” to the accusations against Kavanaugh, “What will happen to our husbands, our fathers, or our sons when a white girl lies on them?”

The woman ends the ad by saying, “We can’t afford to let white Democrats take us back to bad old days of race verdicts, life sentences and lynching when a white girl screams rape.” Robinson ran similar ads on contemporary urban radio in Missouri, Tennessee, Michigan, and Mississippi.

Rep. French Hill, the Arkansas Republican the spot was ostensibly meant to help, was horrified.

“I condemn the ad in the strongest terms,” tweeted Hill, adding, “I do not support that message, and there is no place in Arkansas for this nonsense.” Hill ended up winning the election.

“The congressman (Hill) has to run his own campaign,” Robinson said at the time. “My obligation is to communicate with black voters about the president’s agenda,” he said.

“In spite of the party’s lack of interest in communicating with black voters, those ads are very effective,” Robinson told me, “because when black voters hear, in many cases for the first time, that the candidates they have been voting for support Planned Parenthood and the holocaust of 21 million dead black babies and the selling of body parts, that has an arresting influence on their enthusiasm.”

Robinson considers his most successful effort to date his campaign to draft Ben Carson to run for president. He started a super PAC in 2013 that eventually raised more than $17 million.

Most of the funds were used to pay fundraisers and mail vendors. In 2014, the prodigious fundraising of the Draft Ben Carson super PAC raised eyebrows at the Washington Post, which noted most of the group’s money was going to two vendors, Omega List and Campaign Funding Direct.

Bruce Eberle, the founder of both vendors, began a test solicitation on behalf of Carson on August 16, 2013. When the donations began pouring in, Eberle sunk even more money into fundraising. By the end of 2013, Draft Ben Carson raised $1.2 million, with more than 75 percent going to pay for fundraising through services and lists tied to Eberle himself.

Aside from paying vendors to raise the money, not all the expenditures were directed toward coaxing Ben Carson to run; during the 2014 election cycle, Robinson spent more than $500,000 to help defeat Democratic Sen. Mary Landrieu in Louisiana and to boost Republican Thom Tillis in his successful Senate race against North Carolina Sen. Kay Hagan.

Carson actually credited the group with convincing him to get in the race, citing their success in fundraising as a factor. Nonetheless, a phone call to Carson may have been more cost-effective.

Carson eventually dropped out of the race in March 2016.

Meanwhile, Eberle paired with his wife to give Black Americans to Re-Elect the President $50,000 in late June of this year. It has been a solid investment for him—the super PAC has paid Campaign Funding Direct and Omega List a total of $351,000 during the 2020 cycle. Eberle and Robinson have even authored a book together called Coming Home: How Black Americans Will Re-Elect Trump.

In 2016, FEC commissioners Ellen Weintraub and Ann Ravel issued a letter warning about the proliferation of what they deemed “scam PACs” during the 2020 election cycle. In order to spot scams, wrote the commissioners, one should look for political committees that “collect political contributions, frequently using the name of a candidate, but which spend little to none of the proceeds on political activity benefitting that candidate.”

Further, they warn that common characteristics of scam PACs are “high operating expenses and/or large disbursements to entities associated with the managers of the PACs.” Recently, Democratic Rep. Katie Porter of California and Republican Rep. Dan Crenshaw of Texas introduced a House bill to more tightly regulate alleged “scam” PACs.

Other PACs have used the names of potential candidates to raise money, including committees to elect former Rep. Allen West, talk show host Laura Ingraham, and former Milwaukee Sheriff David Clarke. All used the names and likenesses of these individuals without their consent. But the FEC has frequently dismissed such complaints, claiming nobody is being defrauded when such a PAC operates.

University of Wisconsin-Madison political science professor Kenneth Mayer, who studies campaign finance law, told me there’s really no way to separate these unauthorized campaign committees from “legitimate” PACS.

“This is one of the things I think you can attribute to Citizens United,” Mayer told me, noting PACs participating in political activities before the landmark Supreme Court case were bound by a $5,000 contribution limit. “That limited the scope of these kinds of things because it takes a lot of work to raise that kind of money in $5,000 chunks,” said Mayer.

“The problem is, how do you write down a rule that says ‘this is the line?’” Mayer said, noting the difficulty in deciding which super PACs operate within the spirit of the law. “Who’s going to decide?”

Regardless of who’s benefiting from his spending, Robinson’s style may earn him more donors and more mainstream acceptance. In 2017, Trump-friendly Newsmax ranked him as the nation’s 18th most influential African American Republican.

Robinson does have some mainstream conservative positions he thinks will draw African Americans to the polls, including support for school choice, vouchers, and charter schools.

Robinson, who has run unsuccessfully for North Carolina School Superintendent twice (in 1992 and 1996) told me he’s going to run a school choice ad against Biden because “almost all Democrats send their kids to private school, then deny poor kids school choice because they have to pay off the union.” And he sounded downright giddy when reciting a line in his jobs and wealth creation ad: “The only private sector job that Joe Biden has ever created was one for his son in the Ukraine.”

“My ads tend to be tough,” he said, adding his abortion ads will end with “every time Joe Biden asks for your vote, ask him why he doesn’t want our children.”

Robinson said when black voters hear ads like that, two things happen—they either stay home or more of the black voters that do go to the polls vote for Republicans.

But even if there are issues on which African Americans lean conservative, two big issues threaten to drive black voters away from him: The protests that followed George Floyd’s death, and Trump’s handling of the pandemic, which has affected blacks disproportionately. In regards to the latter, Robinson blames Democrats and their leadership for poor black health. “If you’re in a single-parent household, you’re going to have all sorts of medical problems associated with poverty,” he said, while claiming that Black Lives Matter wants to get rid of the patriarchal nuclear family altogether.

It didn’t take long after Biden announced Kamala Harris as his running mate for Robinson to start making plans for his messaging. “How did she move from first Indian American senator to first black Veep qua Presidential nominee? [I say] presidential because Biden has dementia and while his wife would like to do a Wilson and run the country, those pulling his strings have decided that after 25th Amendment removal, Harris would be the best president.”

Never mind that Trump supporters howled when critics raised the idea of removing him from office via the 25th Amendment. Robinson is pulling no punches. And he’s frustrated by those who do.

“There’s a cultural war going on and only one side is fighting. Republicans are still in this dreamland that they’re back in the days of Tip O’Neill having a scotch with Ronald Reagan,” he said.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.