Sweeping police reform is stalled in Congress: The House passed a bill last week that the Senate appears to have no plans to take up, while Sen. Tim Scott’s JUSTICE Act failed to get enough votes to advance to debate. But, a bipartisan group of senators is still pushing for incremental reform. Amid growing concerns over racial inequality in the criminal justice system, “civil asset forfeiture” is facing renewed scrutiny.

On June 25, Sens. Rand Paul, Angus King, Mike Crapo, and Mike Lee reintroduced their bill, the “Fifth Amendment Integrity Restoration Act,” to limit civil asset forfeiture and restore due process rights.

Through civil asset forfeiture, federal and state-level law enforcement can seize private property they merely suspect is related to some criminal activity. Examples of seized property include cash, vehicles, and even homes. No charges or convictions are required for police to confiscate this property. (Alternatively, in the less-common process of criminal asset forfeiture, a conviction is required.) In an inversion of the principle of “innocent until proven guilty,” Americans must pursue a lengthy, complicated, and costly appeal process to get their property back.

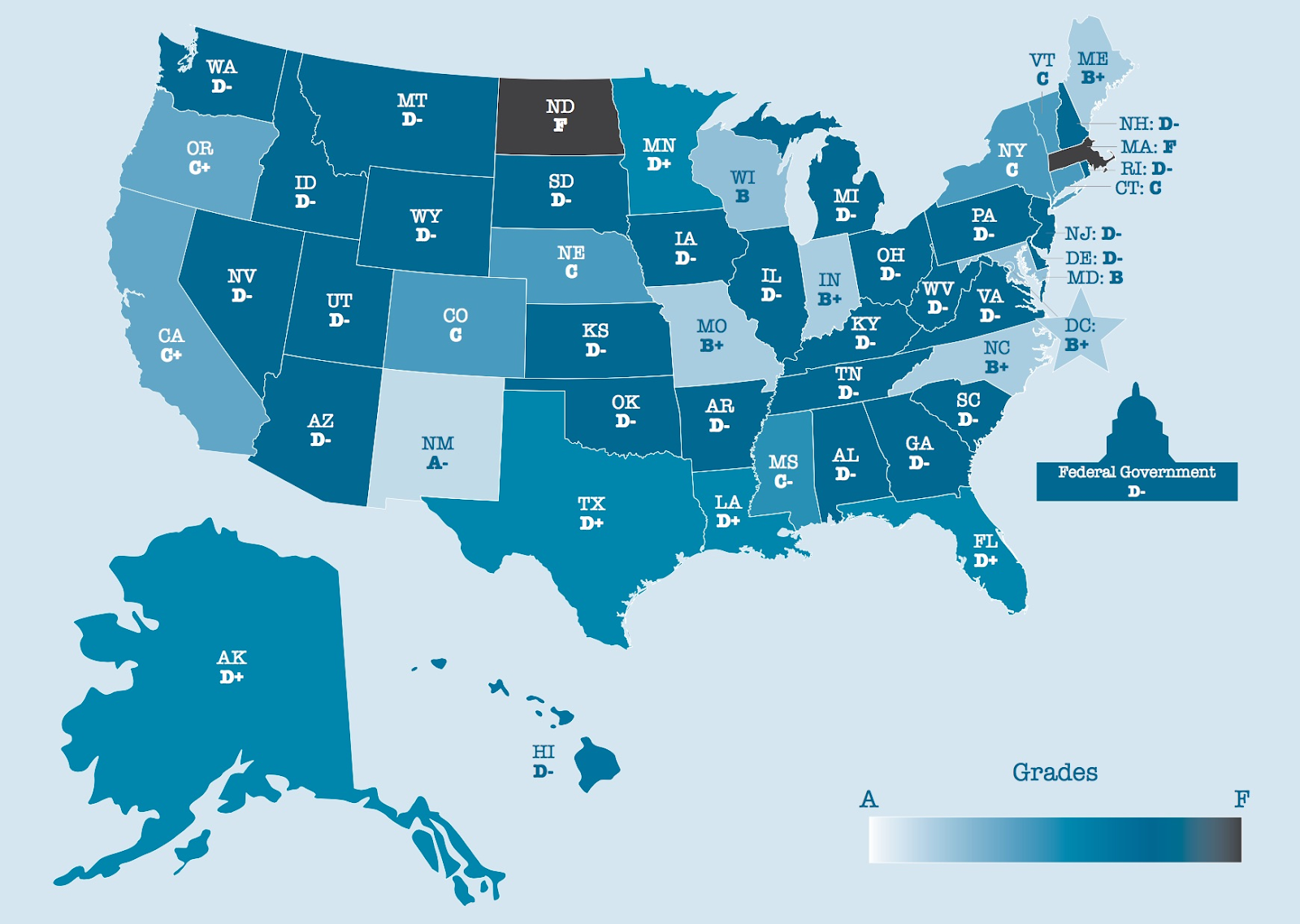

According to the public interest law firm the Institute for Justice (IJ), the Department of Justice takes in roughly $4.5 billion annually from civil asset forfeiture. And it happens at the state level in most of the country as well. Texas, for example, took in $50 million in 2017 through criminal and civil asset forfeiture combined. IJ examined the fairness of civil asset forfeiture laws to grade all 50 states and gave 35 a “D+” or worse.

(Image: Institute for Justice)

Why are law enforcement agencies so aggressive with the practice? Critics describe it as “policing for profit.”

Per the Institute for Justice, “In 43 states, police and prosecutors can keep anywhere from half to all of the proceeds they take in from civil forfeiture.” The assets go into their own department’s coffers, not back into the general treasury.

Examples abound in which innocent citizens are punished under the forfeiture system. Take Isiah Kinloch’s story, reported by the Greenville News, for example.

In 2015, Kinloch fought off a burglar who tried to break into his apartment. When he called the police, officers found a small amount of marijuana in the apartment and, without any evidence of a connection, seized $1,800 in cash they found in the home.

Drug charges were filed against Kinloch but later dropped, and he was never convicted of any crime. Police kept the cash.

In another example, a taco truck driver had $10,000 seized by the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department even though he was never arrested or charged with a crime. He was never able to recover the funds.

And as the Pittsburgh Post Gazette reports, police confiscated $15,000 that Colombian immigrant Miladis Salgado was saving for her granddaughter’s quinceañera. Their only basis? A tip, which later proved unfounded, that Salgado’s husband might be selling drugs. She eventually got the money back but her $5,000 in legal expenses were never recovered.*

There’s reason to believe that civil asset forfeiture disproportionately affects racial minorities. As part of their two-year investigation into asset forfeiture, the Greenville News found that in South Carolina, “Seven out of 10 people who have property taken are black, and 65 percent of all money police seize is from black males.” The newspaper’s investigation only applies to one state, but academic studies have found that the racial diversity of a municipality positively correlates with the amount of property seized by law enforcement.

This perceived injustice is motivating Paul and Lee’s renewed legislative push to reform civil asset forfeiture.

“The federal government has made it far too easy for government agencies to take and profit from the property of those who have not been convicted of a crime,” Paul said in a statement.

“While we certainly want to ensure that law enforcement has the tools they need to fight crime, the federal government should not be wrongfully taking our citizens’ private property and denying them due process under the law,” Lee added.

One key reform included in the bill is the elimination of something known as “equitable sharing,” where local law enforcement can circumvent state laws limiting forfeiture and turn proceeds over to the federal government for a cut of the profits. So, too, the senators’ bill eliminates the profit incentive driving much of this seizure by mandating that federal forfeiture proceeds are deposited in the general Treasury fund, not the DoJ’s personal piggy bank.

This is how it used to work. Then, in 1984, Congress created the profit motive with changes to and expansions of the forfeiture system that allowed some of the funding to go back to police departments. Perhaps unsurprisingly, IJ finds that “the use of forfeiture at the federal and state levels exploded once profit incentives kicked in.”

Rand and Lee’s bill would restore this aspect of the forfeiture system to its previous state, which was far less prone to injustice and abuse. Importantly, their legislation also contains key due process and procedural reforms.

For one, the FAIR Act would mandate that Americans who cannot afford a lawyer have the right to a court-appointed attorney in all forfeiture proceedings, which somehow is not currently the case. It also raises the standard of evidence in asset forfeiture cases, and it increases damages awarded in wrongful forfeiture cases threefold, to discourage abuse and make it worthwhile for victims to pursue justice even when legal expenses may exceed property values.

Of course, passing one bill wouldn’t eliminate the need for the many other criminal justice reforms that have been discussed in the wake of George Floyd’s killing. But rolling back civil asset forfeiture offers a great starting point, and presents a rare opportunity for groups from across the political spectrum, from the ACLU to conservative and libertarian think tanks, to come together and help Americans.

Brad Polumbo (@Brad_Polumbo) is a libertarian-conservative journalist and former fellow at the Washington Examiner.

Photograph by Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images.

Correction, July 2: This article initially claimed, incorrectly, that Miladis Salgado recovered not only the money that had been confiscated but also her legal expenses.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.