Eatonton, Georgia, doesn’t see too many politicians coming through. So when Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams stops in the town of 6,000 an hour east of Atlanta Wednesday evening, a good-sized and cheerful crowd turns out despite the lingering heat, lounging in lawn chairs and cooling themselves with “I’m a Fan of Stacey Abrams” fans provided by the campaign.

“We are 62 days away from glory—62 days away from changing the future of this state,” Abrams tells the people assembled at the city center stage. “We got the money already. We’ve got the people. We’ve got the power, but we need the leadership. We don’t have to raise taxes. We just have to raise our expectations.”

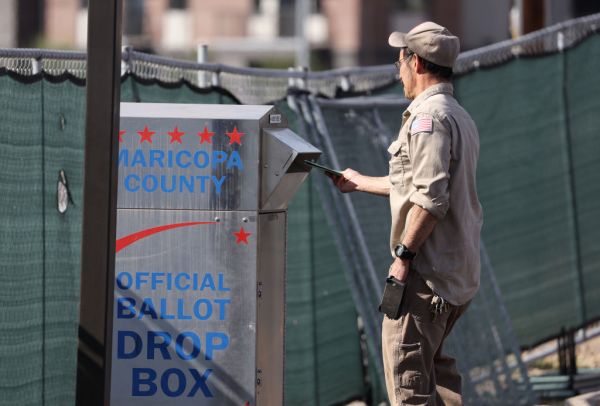

Abrams has been changing the future of Georgia for a while already. In fact, though she’s never held statewide or national office, there’s little doubt that the former minority leader of the Georgia House has been one of the most pivotal American politicians of the last few years. Her voter-registration efforts are widely credited as the driving force behind the Peach State’s recent red-to-purple turn—a phenomenon that set the stage for Georgia Democrats to score two huge runoff-election Senate upsets against GOP incumbents in 2021. Those seats handed Chuck Schumer control of the Senate and crushed Republicans’ best hope to stymie President Joe Biden’s agenda in Congress.

But while she’s improved the fortunes of Democrats all around her, there’s been an “always the bridesmaid” feel to Abrams’ personal political career, which has recently been marked mostly by disappointments: edged out by Republican Brian Kemp in the 2018 governor’s race, shortlisted as a possible running mate but ultimately passed over by Biden in 2020. And today, despite rising Democratic hopes for the midterms around the country—and despite the odds looking good that one of those new Georgia senators, Raphael Warnock, may stave off Republican challenger Herschel Walker—Abrams has stayed flat in the polls, facing the same rough five-point deficit she’s seen against Kemp since January.

On paper, Abrams goes into the contest with several major advantages. Her strong national brand has enabled her to raise eye-watering sums of money: Her May and June fundraising haul (the latest numbers the campaign has been required to disclose) more than tripled Kemp’s, and her campaign had more than $18 million on hand at the end of that reporting period. (Kemp ended the period with $7 million in the bank.)

Abrams has used that cash to hammer Kemp on the airwaves. With the economic climate favoring Republicans going into this year’s midterms, she’s focused her critiques primarily on social policies—in particular, Kemp’s conservative stances on abortion and gun rights. There’s reason to believe the former critique in particular is fruitful territory for Abrams: In a July Atlanta Journal-Constitution poll, 42 of respondents said a candidate’s support for legal abortion would make them likelier to earn their vote, while only 26 percent said they’d be likelier to support a candidate who promised to limit abortion access. A heartbeat law outlawing most abortions after about six weeks of pregnancy, which Kemp signed in 2019, only recently went into effect following the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade; a typical Abrams ad calls the law “an attack on the women of Georgia.”

While she blankets the major media markets with these ads, Abrams tweaks her focus in small-town and rural Georgia. Putnam County, of which Eatonton is the seat, broke for Kemp in 2018 by a 45-point margin and for Donald Trump in 2020 by 40; narrowing that gap outside the cities will be crucial if Abrams is going to outpace her 2018 showing. Here, her first message out of the gate is in part an economic one—a critique of Kemp’s decision not to fully expand Medicaid in the state, which she cast as a blow to health care for poor and rural Georgians. (Kemp opted for a partial Medicaid expansion in 2019, but Georgia remains one of 12 states that has resisted full implementation of the federal program expansion.)

“If you make $9 an hour, you are considered too wealthy for health insurance from the state, but you’re too poor to get it anywhere else,” Abrams says. “Brian Kemp is saying no because he doesn’t think Georgians deserve access to health care.”

(Asked for comment, Kemp press secretary Tate Mitchell replied that “Under Gov. Kemp’s leadership, Republicans have passed over 50 healthcare bills to lower costs and expand access, including waivers to increase competition and drive down costs throughout the state.”)

Naturally, Abrams still hits guns and abortion here as well. Martha Harris, who lives in neighboring Hancock County, told The Dispatch prior to Abrams’ arrival that she was “all about inclusiveness and women’s rights” and was eager to hear Abrams’ take on social issues, given that “I know that she was not pro-choice at one point in time.” (Abrams has previously spoken about how she grew up opposing abortion before changing her mind in college.) When Abrams pivots to attacking Kemp’s record on abortion, Harris’ shouts of “hell yeah!” are loud enough to draw scattered laughs from the rest of the crowd.

It’s plain a lane is there for Abrams. Whether she can close the deal is another matter. She remains a polarizing figure in Georgia, having long denied the legitimacy of Kemp’s 2018 election and struggled to distance herself from what she describes as unfair Republican attacks that she supports defunding the police. (Abrams has said she would support reallocating some police funding to other community services in some circumstances, although she argued at the same time that pitting the two against one another represents a “false choice.”)

There have also been some goofier gaffes—an elementary school visit back in February that provoked an uproar after Abrams was photographed maskless in the midst of dozens of masked children, her assertion that she was “tired of hearing about being the best state in the country to do business when we are the worst state in the country to live.”

Meanwhile, Kemp is a formidable opponent, as his triumph over a Trump-backed primary opponent earlier this year proved. He has paired conservative ideological plays like the heartbeat bill with a general pro-business outlook that has buoyed the state’s economy, which also benefited from his willingness to let Georgia reopen relatively quickly during the COVID pandemic. And he has made moves to blunt the pain of inflation this year, suspending the state’s gas tax and giving raises to public school teachers, which have been broadly popular in the way free-money policies tend to be.

Kemp trails Abrams in campaign finances, but is a tireless campaigner with an unparalleled network of contacts around the state. The stubbornness of his lead has led to some grumbling by state Democrats and at least one behind-closed-doors acknowledgement from Abrams that Kemp is likely to be the toughest Georgia Republican to beat this year.

Still, Team Abrams argues there’s time to make a late push. The campaign’s latest internal polling has her only two points down on Kemp, within the margin of error.

“This latest poll makes it clear that our campaign has the momentum as we head into the last 10 weeks of the race,” campaign manager Lauren Groh-Wargo says. “We will continue to travel around the state, hearing from and listening to Georgians as we work to build One Georgia and stop Kemp’s radical far-right agenda that endangers the lives and livelihoods of Georgians.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.