The past few years have made clear that most of American politics—not just progressive politics—has become centered around identity and not governance. A recent New York Times piece by Stephanie Muravchik and Jon A. Shields documenting Rep. Liz Cheney’s primary loss drives this point home, noting that Republicans “are succumbing to the same impulses they associate with their liberal opponents: a shrill hostility to different viewpoints, an obsession with virtue signaling and a willingness to purge their own ranks.” So too with the increasing contempt that Republicans and Democrats feel for one another. As Jonathan Rauch memorably put it in National Affairs: “We are not seeing a hardening of coherent ideological difference. We are seeing a hardening of incoherent ideological difference. … What if, to some significant extent, the increase in partisanship is not really about anything?”

This uniquely abstract form of politics likely cannot go on forever, as the Times authors note, because “any party that elevates symbolism over governing risks stirring mass revolt down the road. … Results matter even in the age of identity politics.” But an awful lot of damage can be done in the interim before reality comes crashing down.

Localizing more issues might help concretize our politics—to make it more about real policies than symbols, resentments, and identities. But even if our nationalized status quo doesn’t budge an inch, there are reforms to be had at the federal level—particularly in Congress—that could help make politics more about something again.

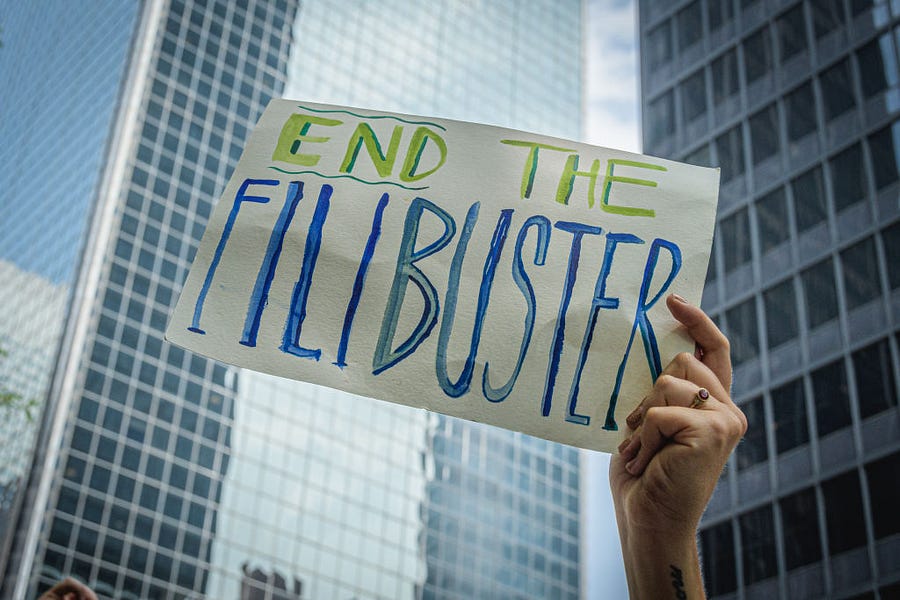

One step that could work is to transform the Senate filibuster. Calls from the left to abolish the filibuster outright have become louder and more frequent, and are the result of frustration among progressives that they can’t easily push their agenda through Congress. Ending the filibuster altogether has its problems, but if done properly, reforming the filibuster could make it a tool for fostering a politics that is grounded more in issues and less in identities.

Congressional dysfunction breeds popular dysfunction. Although we don’t like to admit it, our leaders (particularly those of our own party) shape our perceptions of politics. When they can’t work together and do anything meaningful with those on the other side of the aisle, many of us internalize the message: The other side is hopelessly misguided or hateful, and the only path forward is to win at all costs and go it alone.

But a Senate governed by simple majorities could further heighten the stakes of national elections and enhance partisans’ threat perceptions and fears of one another. Scrapping the filibuster could further divide us.

Maintaining the status quo has considerable drawbacks: If normal legislation can pass the Senate only with a 60-vote supermajority and neither party is willing to compromise when it’s in the minority, not much gets done except in the event of a crisis or through reconciliation. Politicians make promises, nothing happens, and the people grow frustrated. Most of us sit on the sidelines, leaving only the most zealous left on the political playing field. It’s a nasty, self-perpetuating cycle.

Moreover, the actual concrete stakes of politics become rather low. This incentivizes us—citizens and politicians alike—to act like the most irresponsible versions of ourselves in the political realm. Words no longer have consequences. We double down on our identities, symbolism, and vague and overblown rhetoric, raising the temperature of a politics where partisan fights aren’t exactly about anything concrete anymore.

So, if we’re concerned about division, scrapping the filibuster doesn’t seem like the best idea, but neither does maintaining the status quo. Maybe there is a way out of this morass.

Perhaps clearing the filibuster’s de facto 60-vote hurdle to pass legislation should be just one of two ways to pass normal legislation through the Senate rather than the only way.

By revising the rules of the filibuster, a piece of legislation could pass through the Senate in either of two ways:

First, legislation could immediately pass with a 60-vote filibuster-proof supermajority—as is the case today. Plenty of legislation, particularly time-sensitive legislation with a broad basis of bipartisan support like the COVID relief bills of 2020 and 2021, already passes under this framework.

Second, if legislation can’t attain the 60 votes required to invoke cloture and end debate, it should be able to go through the Senate with a bare majority (50 votes plus a vice presidential tiebreaker, or 51 votes), with a crucial caveat: It would have to pass again the next Congress before being sent to the president’s desk.

Under this proposal, the Senate rules would be changed so that a bill destined to fail the 60-vote cloture threshold could instead be put up for a vote to the entire Senate sitting as a “committee of the whole.” Thus, its passage would not trigger the presentment requirement of Article I Section 7 (if the House has already passed the bill). Then, bills that have passed the Senate’s committee of the whole via simple majority in the prior Congress would be taken up at the beginning of the new Congress, with a filibuster carveout in effect (i.e., these bills passed by the committee of the whole would be able to make it to a floor vote with just a simple majority). If a bill makes its way through the Senate on round two, it would have to pass through the House again since it’s a new Congress.

What would this look like in action?

Say the Senate was able to muster 55 votes for a comprehensive immigration reform package. Fifty-five doesn’t equal 60, but instead of letting the immigration reform legislation die at the hands of the filibuster, this second option would allow the bill to stay alive within the Senate sitting as a committee of the whole. Then, it would sit in the Senate—not yet triggering the presentment requirement of Article I Section 7—until the start of the next Congress. Next, for the bill to become law, the Senate would have to repass the legislation with a bare majority during that next Congress following the election cycle. The bill would then have to pass through the House again and be signed by the president.

The key value-add of this reformed filibuster would be its effect on our political discourse: It would help clarify the stakes of campaigns, thereby nudging us (and our elected leaders) to focus a bit more on the actual pending bill and the policy questions it encompasses.

Making available this second, simple majoritarian but slow-moving route to passing legislation could help make our elections revolve around tangible issues—indeed, actual legislation!—once again. Senators and their challengers would campaign on whether they support X bill, which had passed through the Senate committee of the whole. That, in turn, could help turn down the temperature as we inch back toward a more concrete and less symbolic politics. We would be debating—and candidates would be forced to run on—actual legislation rather than vague, often unattainable promises or fear-driven, overhyped accusations regarding the other side of the aisle. Then, the American people would have the chance to indirectly voice their opinion on the most relevant pieces of legislation, as they could choose to elect a pending bill’s supporters or its opponents.

Having this second option available for passing legislation in the Senate could also save us from rash legislation that could fundamentally alter American life with a bare majority because, by design, it would build in a cooling off period. The legislation would have time to percolate through the public square before gaining the force of law. Americans could have time to formulate informed opinions regarding it—and frankly, so too could our politicians for a change. In fact, it might even bring more Americans into the political process. While appearing on The Remnant podcast with Jonah Goldberg, Sen. Ben Sasse once stressed how so many centrists have washed their hands of politics; they have ceded the political playing field to the politically addicted extremists. They see a politics full of fringe policy proposals and heated, bad-faith arguments, and they conclude that their time is better spent on alternative pursuits. This amended filibuster proposal stands the chance of pulling some of those centrist types back into the political fray, because it will make the stakes of politics clearer. It will make the (as of now) fairly rational calculation to sit on the political sidelines a bit less rational.

In sum, this revised filibuster rule could advance both democracy (the most legitimate, nonpartisan call to arms of the filibuster’s detractors) and deliberation (the most legitimate, nonpartisan rallying cry of the filibuster’s defenders). In addition, it might even help foster a less extremist politics.

The net result of this would be a more democratic, yes, but also a more reasonable legal regime. As founders like James Madison well understood, time and reason go hand-in-hand in day-to-day life as well as in politics. Legislation that takes longer to pass is more likely to be the product of reason than passion. At the same time, Madison was a majoritarian through and through; the minority ought not be empowered to indefinitely block the majority’s (constitutional) will.

By championing this additional option as an alternative to the standard filibuster-proof supermajoritarian path of passing legislation through the Senate, our senators can advance democratic values and lay the groundwork for a more reasonable, less vitriolic, less divisive, and more concrete politics.

This might help bring a much-needed dose of reality back to American politics—before it’s too late.

Thomas Koenig is a student at Harvard Law School, and the author of the “Tom’s Takes” newsletter. Follow him on Twitter @thomaskoenig98.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.