Good morning and welcome to the latest in our series, “The Biden Agenda.” We’ve invited some of the smartest thinkers and subject-matter experts we know to contribute to what will become an occasional series on what a Biden presidency might look like. Today, Steven F. Hayward, a climate-policy expert and resident scholar at the Institute of Governmental Studies at UC-Berkeley, examines Biden’s pledges related to climate change. Please see our past entries from Scott Lincicome on trade and James C. Capretta on health care.

With informed reports holding that Joe Biden sees the prolonged pandemic crisis and aftermath of the Trump presidency presenting a second New Deal moment in American history that calls for “going big” on sweeping economic and social restructuring plans, it is no surprise that he has thrown in with the “Green New Deal.” The biggest question about Biden’s plans is where each major element in his agenda will end up on the hierarchy of political priorities if he wins in November, and whether climate change will be a top-tier item.

Already we can see Biden straining to link climate with other top-tier issues into a seamless package. Hard-core climate change activists—many now styling themselves “climate hawks” for whom anything less than radical steps are insufficient—harbor bad memories of the Obama administration, when climate change took a back seat to other political priorities. Many of those remain top priorities for a potential Biden administration, especially the perennials such as health care, education, new pro-union laws, and immigration reform. They’ll be joined this election season by racial justice programs and perhaps a universal basic income. So while Biden appears to be proposing to go far beyond the climate ambitions of the Obama presidency, it still likely won’t be enough to satisfy the climate hawks.

About all the climateers got out of Obama was a string of subsidized green-energy bankruptcies, plus an unambitious regulatory scheme for the electricity sector and Obama’s signature on the largely toothless Paris Climate Accord. Trump swept away the latter two with Obama’s leftover pen and phone. Meanwhile, old-fashioned fossil fuel energy sources, with the exception of coal, prospered during the Obama years, especially the natural gas boom brought about by fracking. Cheap natural gas—never part of Obama’s intended policy mix—accounts for most of the substantial reduction in U.S. greenhouse gas emissions over the last 15 years as gas-fired electricity became cheaper than coal. Plus, the domestic oil boom reversed decades of falling U.S. production and has favorably disrupted global petropolitics. It is possible that without the fossil fuel energy boom of Obama’s first term, he might have lost re-election in 2012, as it was about the only sector of the post-crash economy that grew substantially.

Biden, a practical and calculating politician if nothing else, likely understands this, which is why he has hedged on certain key points like fracking. While climate hawks (and several of his defeated rivals for the nomination) want all fracking banned everywhere immediately, Biden has pledged only to restrict new fracking and new oil and gas leases on federal land, and he has equivocated even on this. Biden’s “federal lands only” oil and gas policy could, ironically, shore up energy producers in existing fields on private and state land, many of whom are under severe pressure at the moment because of low energy prices.

In fact, some Wall Street analysts have upgraded domestic oil and gas companies they think will prosper under Biden’s proposal. While the climate hawks demand a “leave it in the ground” policy for fossil fuels, Biden’s proposal might be described as “leave some of it in the ground.” The climate hawks are not pleased and are grumbling about this deficiency.

As is typical for campaign proposals, Biden’s climate change plan is long on aspirations and goals, and light on details beyond offering a large spending pledge—$1.7 trillion in his first term—as his down payment. That figure might once have seemed eye-popping or absurd (the famous Obama stimulus of 2009 offered only $38 billion for energy initiatives). But at a time when Congress and a Republican president suddenly spend $3 trillion without batting an eye—and with seemingly no ill effect on interest rates or inflation—this figure could turn out to be modest. Bernie Sanders, after all, called for spending $16 trillion on the climate over the next decade, more than twice as much as Biden’s spending rate.

With the magical “modern monetary theory” firmly in the saddle (thus solving the Margaret Thatcher problem of “running out of other people’s money”), we shouldn’t be surprised to see upward pressure on the climate spending pledge. If nothing else, $2 trillion will float a lot of new Solyndras—the solar company that Biden praised as a source of “good, permanent jobs” when it opened, only to cost taxpayers $535 million when it went bankrupt. Solyndra (and similar green energy subsidy failures in the Obama years) may be forgotten now, and it doesn’t seem as though Biden learned much from it: He now says, “When I think about climate change, the word I think of is ‘jobs.’”

As addled as Biden seems at times, it is doubtful he will repeat Hillary Clinton’s mistake of saying “we’re going to put a lot of coal miners out of business,” even though his plan will surely do so and he foolishly agreed during one of the Democratic debates with the idea that lots of current energy jobs will need to be ended. Expect for his proposals to be wrapped up in a new “stimulus” or infrastructure bill (with a side order of “environmental justice” to thrill the race mongers), perhaps offering subsidies and tax breaks for more renewable energy projects and collateral projects such as new electricity transmission lines and development and deployment of battery technology. It is certain to be a rent-seekers delight, and a boon to the many private partnerships that currently harvest the tax code and renewable power purchase mandates for guaranteed profits. Treating energy as a jobs program is a recipe for policy mistakes and outright failures.

It was a given that any Democratic nominee would pledge to rejoin the Paris Climate Accord that Trump threw in the trash can, but in one concrete target Biden promises to go well beyond the ambitions of Obama’s Clean Power Plan (CPP) for the electricity sector. Whereas the Obama CPP called for reducing electricity sector greenhouse gas emissions by 32 percent by the year 2030, Biden wants our electricity supply to be 100 percent carbon-free by 2035.

Biden probably can’t set after this ambitious target through the regulatory means Obama attempted to use (the Clean Air Act of 1970, written for conventional air pollutants of a very different nature than carbon dioxide), and would likely need new legislation from Congress that will essentially nationalize the nation’s electricity sector. Even a lot of green liberal states will balk at the total centralization of electricity policy. (Biden’s proposal implicitly recognizes this, saying that “he will demand that Congress enact legislation in the first year of his presidency” and that if it fails to do so, “Biden will hold them accountable.” It will be amusing to watch him campaign against Sen. Joe Manchin in a future election cycle, like FDR against anti-New Deal Democrats in 1938.)

The complete decarbonization of the electricity sector in 15 years would be prohibitively expensive if not impossible in practice, and can only be achieved the old-fashioned way—by cheating. In addition to the prospect of counting “offsets” such as massive tree planting and perhaps buying “carbon credits” from some new international market, the Biden plan promises more funding for research and development of carbon capture and sequestration technology (CCS), which after 20 years of research is still not affordable or scalable. Many environmentalists are unimpressed. In a roundup of criticisms from climate hawks, Gizmodo worries that “the plan’s bright spot on bringing the electricity sector’s emissions to zero by 2035 could end up being a mirage.”

In any case, the electricity sector accounts for only about a third of U.S. total greenhouse emissions. The other two-thirds come from transportation, household consumption, and other commercial and industrial activity, all of which depend heavily on carbon-producing fossil fuels. These facts become crucial when set against Biden’s larger target of reaching “net-zero” emissions by the year 2050. (Again note the cheating term “net-zero.”) Literally achieving this target requires phasing out nearly all oil, gas, and coal from the energy mix (the U.S. arguably hasn’t been carbon-neutral since the mid-19th century, if then—in other words, before coal, oil, and natural gas came into widespread use). Biden’s plan offers the usual magical thinking that we’ll make a rapid transition to electrified transportation (eventually reaching 100 percent of all new vehicles, but with no time frame specified) and that we’ll retrofit most homes and other buildings in the entire country. No one ever seems to do much math on these schemes, such as how much additional electricity capacity will be required from the supposed carbon-free sector, nor the hugely resource- (and energy)-intensive supply chain for vastly scaled up battery production.

One idea conspicuously missing from the Biden plan is a carbon tax or a border adjustment tax (which complicates the trade problem)—two measures that attract support from across a wide spectrum of the policy wonk world but whose politics remain prohibitive for both parties. On the other side of the ledger, the Biden plan embraces nuclear power, another indication that this once-taboo energy source is no longer under an environmental fatwa. (Even Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has said recently she is “open” to nuclear power.) There is also a nod to “adaptation” to build resilience against natural disasters from any cause.

Even if it lets down the hard-core climate hawks, Biden’s aspirational plan contrasts easily with the Trump administration’s aggressive (and needless) hostility to climate policy, and thus will be enough to fire up the green precincts of the Democratic coalition on Election Day. Right now the Biden plan is mostly bread and circuses, but will get interesting after election day when, if Biden wins, the time comes to put forth proposals with serious details.

Steven F. Hayward is a resident scholar at the Institute of Governmental Studies at UC Berkeley, and author of the Almanac of Environmental Trends.

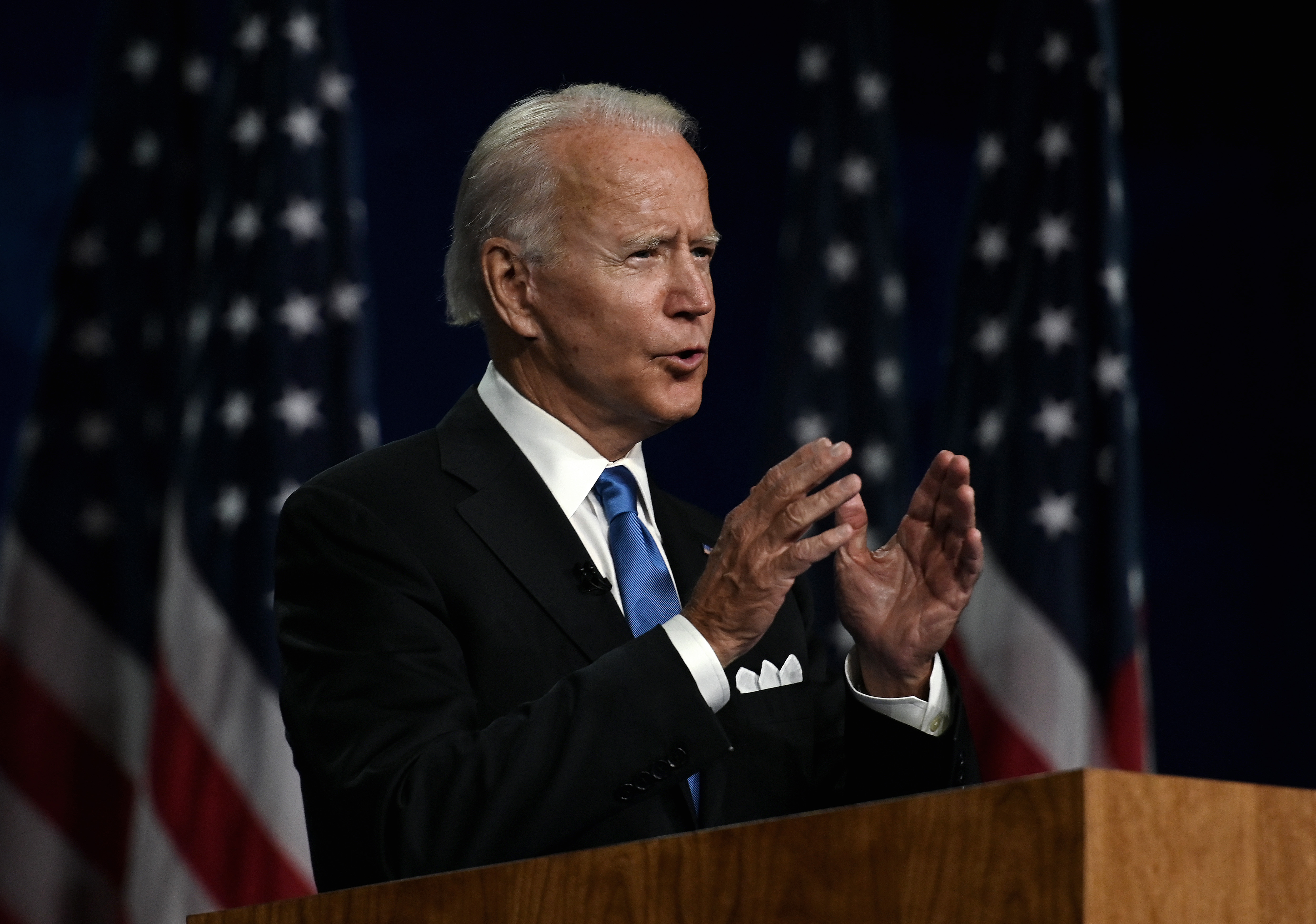

Photograph by Olivier Douliery/AFP/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.