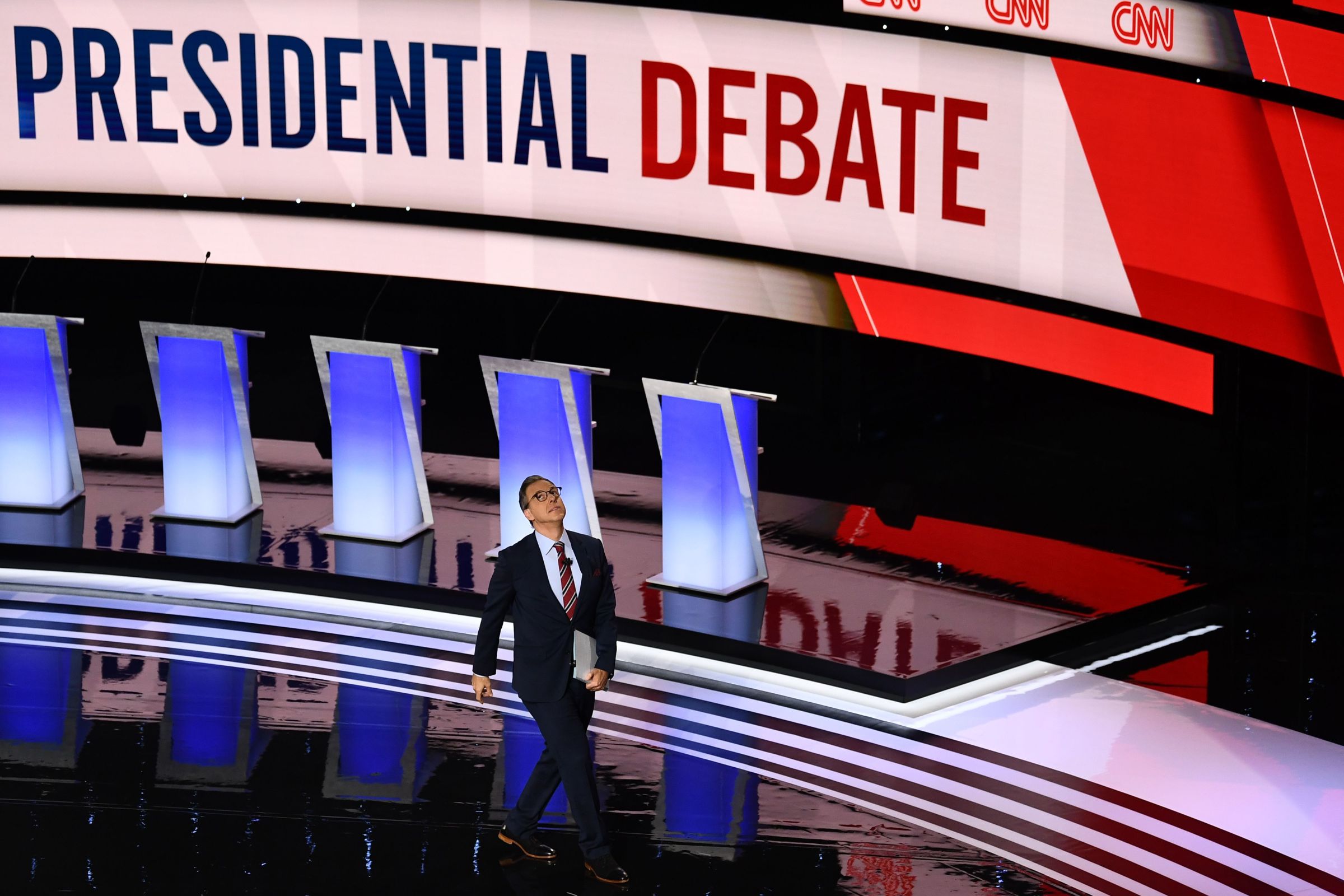

The project of working the refs before the 2024 presidential debates is already underway, with self-abasing Trump sycophants such as Tim Scott insisting that “the moderators will run interference for Joe Biden.” The moderators should not allow themselves to be pushed around, and they should begin the first debate with the obvious question, the one Donald Trump is most eager to talk about:

“Who won the 2020 presidential election?”

Of course, it will seem a little absurd to ask the question with the man who won that election, was sworn in, and currently serves as president standing there on the stage. It is an absurd question. But the absurd question of who won the 2020 presidential election—and who insists on denying the facts about that—is the single most important question in American politics today. The fate of one of the major parties and the broader political tendency for which it stands are together wrapped up in the answer to that question—or, rather, in being able to simply say the answer.

The absurd question of who won the 2020 presidential election—and who insists on denying the facts about that—is the single most important question in American politics today.

Republicans and conservatives remain in a state of willful, culpable denial about what happened after the 2020 election. The Republican Party will not be able to move forward as a normal party until it makes a reckoning for those events, and U.S. politics will remain deformed until the Republican Party either undertakes the necessary internal reforms or—and one solution is as good as the next—disappears entirely.

The hand-waving has been extraordinary—and indefensible. Otherwise generally sensible people such as Rep. Dan Crenshaw pooh-pooh the attempted coup d’état on the grounds that Donald Trump and his partisans acted in part through court challenges and by attempting to sway the actions of political actors—as though it weren’t the case that successful coups typically combine legal or constitutional pretexts, often involving claims of electoral fraud, with political violence and strong-arm tactics. Augusto Pinochet came into power in Chile through just such a coup, arguing that the government of Salvador Allende was unable to perform its constitutional duties and had undertaken unconstitutional actions, a view that was endorsed by Chile’s supreme court. There are many other examples of similar coup careers: Francisco Franco, Fulgencio Batista and Fidel Castro after him, Mobutu Sese Seko. Most of what Adolf Hitler did, he did under color of law: the Reichstag Fire Decree, the Enabling Act of 1933, the Nuremberg race laws. We should not pretend that attempted legal gilding makes a coup any less of a coup. Americans usually can see that when it comes to every country except our own.

Nor should we offer anything except contempt to the line of argument insisting that we should dismiss the attempted coup d’état because it did not come very close to success. There is a reason we have crimes such as attempted murder and conspiracy to commit fraud. And a clumsy, incompetent, and failed coup attempt can do a great deal of damage to a constitutional republic that relies—to a terrifying extent—upon the unreliable virtue of such fickle and weak men as Mike Pence for its security. But the 2021 coup attempt was not as obviously doomed to failure as many on the right now like to pretend: Change four or five decisions made by three or four men and we could have seen a very different outcome.

Many observers have offered amateur psychoanalytic explanations for Trump’s insistence that he won the 2020 election and was defrauded of a second term. Many of these accounts are plausible enough, but there is a more straightforward political version: Trump’s political case for himself in 2016 was that he was a winner—“so much winning” and all that. And Trump did win in 2016—after which he led the Republicans to defeat after defeat, both at the polls and in political negotiations, culminating in his loss in 2020 to Joe Biden, a craven hack who barely bothered to campaign against him. Trump’s repeated defeats and his crowning humiliation at the hands of Democrats in 2020 not only denied him a second term—they also negated, ex post facto, the political argument for his first term as he himself presented it.

To encounter anything other than shame and humiliation in worldly defeat is far too specifically Christian a notion for Trump and the imperial cultists around him to comprehend. Trump’s religion is nostrism (“us-ism,” which is to say, vulgar tribalism), and nostrism doesn’t work when you lose, because you are asking your congregants to unite with defeat rather than with victory.

If Trump cannot answer one simple question—“Who won the 2020 presidential election?”—then the American electorate, as daft and ignorant as it is, should be made to confront that fact and what it means.

If Trump cannot answer one simple question—“Who won the 2020 presidential election?”—then the American electorate, as daft and ignorant as it is, should be made to confront that fact and what it means. Either Trump continues to insist on the legitimacy of his coup attempt or he concedes that his political raison d’être is, and always has been, a combination of delusion and fraud.

That Trump and his cronies believe that their delusion and fraud can be sanctified by an electoral win in November is not entirely irrelevant. But between now and Election Day, the fundamental question must be raised and raised again as often as is necessary.

So, ask the question.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.