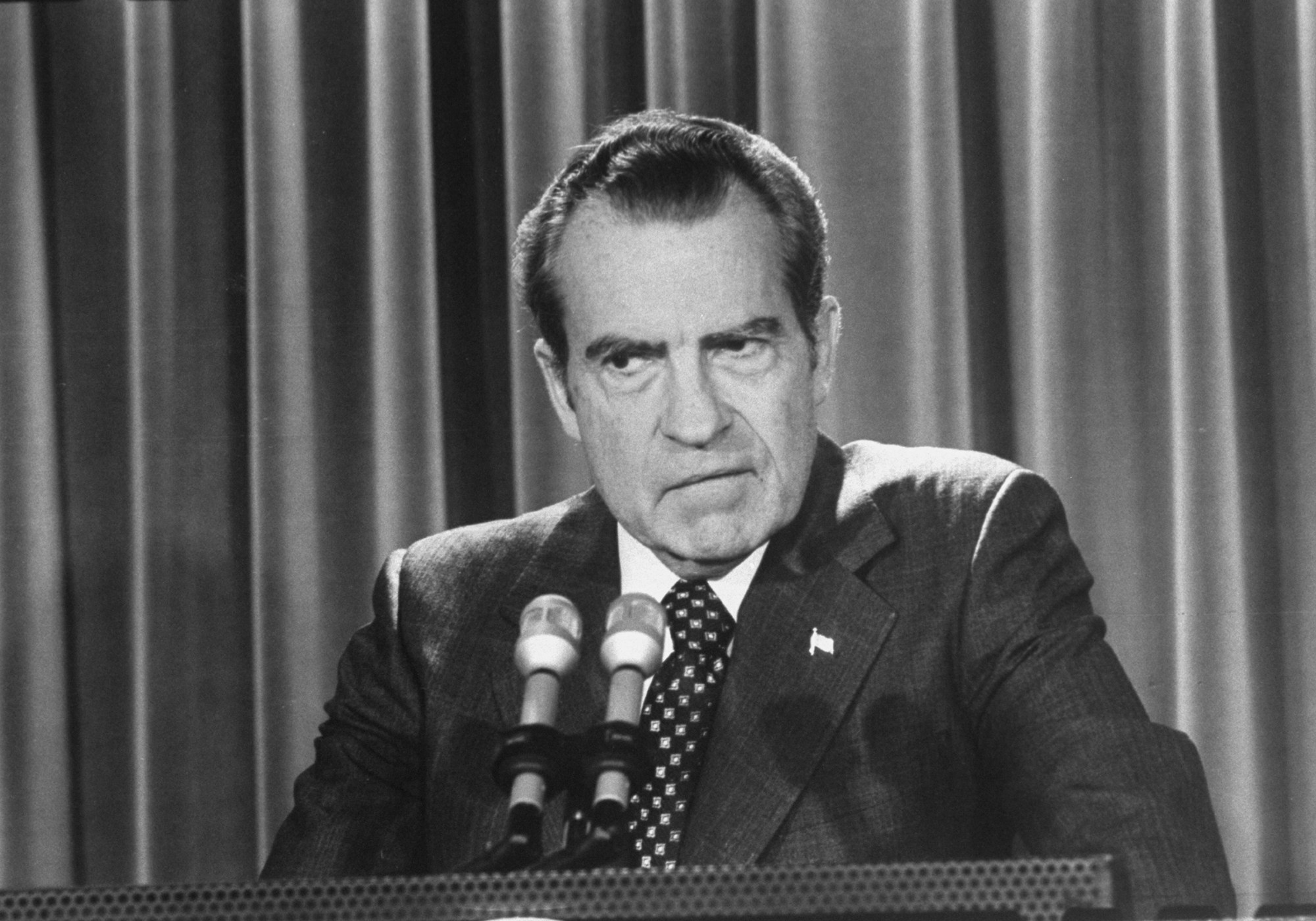

“When the president does it, that means that it is not illegal.”

—Richard Nixon, 1977

“He who saves his Country does not violate any Law.”

—Donald Trump, 2025

Hollywood has led us to believe the myth that authoritarians are hyper-competent, ideologically driven supervillains. The reality is more often the opposite. Authoritarians are small, petty men, obsessed with taking revenge on those who do not share their own inflated sense of self-importance. Their rise to power is a product of structural and civic failure rather than their own brilliance or competence.

President Richard Nixon was a night owl. After the end of official business, he would decamp from the White House to a secret office in what is now the Eisenhower Executive Office Building. He would spend the wee hours of the morning obsessively reading newspaper articles that criticized him, annotating them for his aides, and demanding they find ways to punish the offending journalists and news outlets. One aide complained that he had “logged 21 requests from the President” in a month and he could not satiate Nixon’s obsession for finding enemies. Nixon compiled long lists of his foes with titles like, “Those We Can Never Count On,” filled with hundreds of names.

Nixon’s hunger for retribution against his critics led to the creation of the Committee for the Re-Election of the President (later nicknamed CREEP by the press), a shadowy, semi-official organization that could settle such slights—by illegal means if necessary. When Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times—creating a public relations nightmare for the Nixon administration—CREEP operatives burglarized the offices of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, trying to find embarrassing and discrediting evidence of mental illness. CREEP’s lawlessness ultimately sparked the Watergate scandal, which forced Nixon’s resignation. Live by the obsession, die by the obsession.

President Donald Trump keeps a less nocturnal schedule, although he watches conservative cable news programs for hours every day, frequently calling in to his favorite shows to correct perceived slights. He annotates critical newspaper articles with a sharpie and sends them back to the offending journalists. For instance, after writer Graydon Carter described Trump a “short-fingered vulgarian” in Spy magazine in 1988, Trump spent the next quarter of a century mailing him photocopies of his hands. In the digital era, Trump added the habit of tweeting (or “truthing”) his grievances, up to 200 times a day, or 26,000 times during his first term alone.

Trump’s obsession with settling old scores has been a consistent through-line of the early abuses of executive power during his second term. This is no secret. Trump campaigned on retribution, threatening to go after those officials who attempted to hold him to account for both the January 6, 2021, insurrection and his financial crimes. Since taking office, he has followed through, defenestrating the Justice Department by firing the January 6 prosecutors and stripping security details and clearances from government officials who dared to question him.

But the insult added to illiberal injury is how petty and personal the scores being settled can be. For example, in retaliation for Joe Biden removing several Trump apparatchiks from the board of the Kennedy Center, Trump fired its leadership and installed himself as chairman of the performing arts venue, which he snubbed during his first term.

Likewise, Trump recently fired the head of the National Archives—the usually boring, nonpartisan repository of presidential records because they had the audacity of enforcing the Presidential Records Act when Trump took classified information with him to Mar-a-Lago after leaving office. Trump has even asked his advisers to compile a “list” of the National Archives staff responsible for this outrageous insult so that he can purge them. National archivists typically have a technical or scholarly background, but the primary qualifications of Trump’s chosen replacement, James Byron, are that he was CEO of the Richard Nixon Foundation and wrote a guide to the souvenirs offered in the gift shop at the Nixon Library.

From CREEP to DOGE.

Like Nixon and CREEP, Trump has his own team of loyal operatives willing to bend or break the law in order to root out his internal enemies. Officially, Trump tasked the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) with finding trillions of dollars in waste, fraud, and abuse by federal agencies. Despite its name, DOGE is not an actual executive department; it subsumed the U.S. Digital Service, an IT consulting task force that was a holdover from the Obama administration and which was created to update computer systems, not take over and audit federal agencies. Regardless, teams including teenagers and young 20-somethings operating out of DOGE’s offices, which are just a few hundred feet from the old headquarters of CREEP, have illicitly raided federal agencies including USAID, Treasury, and the IRS to gain access to their internal databases.

One key difference between the two is that DOGE is operating at a scale that CREEP could only have dreamed of. Instead of a handful of Cuban expatriates breaking into DNC headquarters at the Watergate hotel and combing through filing cabinets, DOGE has been systematically vacuuming up the records of millions of Americans. Remember, Nixon’s operatives were hunting for information that could embarrass his enemies and foment his political agenda. DOGE is doing the same by attempting to surface stories of woke DEI excess to embarrass Trump’s enemies and foment his political agenda. (Several of these stories have since been discredited or found to be exaggerated.)

DOGE is also a much higher-profile endeavor. CREEP’s leadership included middling political operatives like Jeb Stuart Magruder and G. Gordon Liddy, whereas DOGE’s head is Elon Musk, the wealthiest man in the world. Whereas Magruder and Liddy held off-the-books meetings with Nixon, Musk holds joint press conferences with Trump.

Targeting ‘fake news.’

When CBS aired coverage critical of the administration’s conduct of the Vietnam War, Nixon sent one of his CREEP operatives, Chuck Colson, to a meeting with network executives. Colson threatened CBS with enhanced regulatory scrutiny under a Federal Communications Commission rule called the “Fairness Doctrine” if the network kept up its attacks. He proudly reported back to Nixon that the intimidation tactic had its intended effect, leaving CBS acting “accommodating, cordial and almost apologetic.” CBS ultimately pulled several of its shows to placate Nixon and FCC Chairman Dean Burch.

Likewise, Trump is picking fights with CBS. His presidential campaign sued the network for its editorial choices in a 60 Minutes interview with Kamala Harris and Trump’s FCC chairman, Brendan Carr—who authored an essay for Project 2025 asserting the FCC’s power to punish platforms that refuse to carry pro-Trump speech—is going after the network. The Fairness Doctrine no longer exists, so Carr is brushing off another obscure FCC regulation from the 1960s/70s, the “news distortion” standard, and is threatening to hold up a proposed merger between CBS parent company Paramount and Skydance over the matter. In an essay I wrote before the election, I warned of this precise scenario.

The purpose behind Nixon’s and Trump’s bullying of news outlets is the same: to intimidate the outlets into self-censorship, creating a chilling effect on negative news to the administration’s benefit. The strategy is working again, with multiple outlets and platforms settling winnable lawsuits on generous terms, overpaying for a documentary about Melania Trump, and preemptively complying with President Trump’s wishes.

(No) checks and (im)balances.

In a very direct way, the Trump administration seeks to unlock the shackles placed on the presidency in the aftermath of Nixon’s betrayal of office. Prior to the scandals of the 1960s and 1970s, most people trusted in the probity and decency of the president and the federal government writ large. In particular, Nixon’s lies and attempted cover-up of the Watergate scandal contributed to a decades long slide in public institutional trust. Congress passed a series of good governance reforms after Nixon’s resignation in an attempt to reassure Americans that the federal government worked on their behalf, not merely to further the corrupt interests of whomever was in charge.

Those reforms included the Impoundment Control Act of 1974 and the Inspector General Act of 1978. The first was meant to create a bright line between the legislative and executive branches regarding who gets to decide how taxpayer money is spent. Nixon had impounded money earmarked to improve New York City’s aging, leaky sewers, a project that he opposed on political grounds. Both Congress and the Supreme Court put him in his place, reminding him that the Constitution vested such power in the Congress and not in the president.

Similarly, Trump’s Office of Management and Budget attempted to freeze all federal funding while it made sure that the money was “dedicated to advancing Administration priorities.” This was not only a bald challenge to the Impoundment Control Act of 1974 but an exponentially greater claim of executive preeminence than any prior example of impoundment in U.S. history. Nixon was sanctioned for withholding money from a single congressional grant. By contrast, Trump attempted to withhold all federal financial assistance, implicating funds granted by dozens or even hundreds of acts of Congress.

The second post-Nixon good governance reform that Trump has challenged is the Inspector General Act of 1978, which created inspectors general as watchdogs against waste, fraud, and abuse at federal agencies. The office was designed to be insulated against executive manipulation by requiring Senate confirmation for these presidential appointees. Yet one of Trump’s first acts as a second term president was to fire 17 inspectors general, a record number, and he did so in direct violation of the law requiring 30 days notice to Congress.

The administration’s only proffered justification was a senior White House official saying that the fired inspector generals did not “align” with the administration’s goals. Trump later issued an executive order giving Elon Musk powers similar to that of an inspector general—to access agency data, interview personnel, and recommend policy changes—but one that sits above even agency heads, has authority over the entire spread of federal agencies, and which is completely unaccountable to Congress.

To impeach, or not to impeach?

Trump is not just mirroring the executive abuses of Richard Nixon. He is surpassing them in every way. Nixon ordered the firing of one special prosecutor; Trump ordered the firing of 17 inspector generals. Nixon impounded money from one program; Trump impounded the entire federal financial aid apparatus. Nixon’s threats to CBS got a few programs pulled; Trump’s threats to CBS might get a corporate merger blocked. CREEP burglarized the contents of a few filing cabinets; DOGE has combed through entire agency databases filled with classified information.

Yet it was Nixon who faced a serious impeachment threat and resigned, while Trump has been impeached twice and avoided conviction twice, largely on party line votes. There is no individual difference between Nixon and Trump that can explain such a wide gulf in outcomes. Rather, it is a difference in the caliber of Republicans then and now.

As evidence of CREEP’s skullduggery and Nixon’s lies to his own party members mounted, multiple GOP senators, including conservative icon Barry Goldwater, approached the president and warned him that they would vote for impeachment if he refused to resign. This was not merely out of principle. As Massachusetts Sen. Edward Brooke put it, “If he [Nixon] doesn’t resign now, serious harm will come to the country and the party.” When Nixon finally agreed to leave, the CBS Evening News led off by saying, “The GOP gave up today on Richard Nixon.”

By contrast, Republican congressional representatives today have little interest in holding Donald Trump to account. North Carolina Republican Sen. Thom Tillis acknowledged that Trump’s impoundment fell “afoul of the Constitution in the strictest sense” but it wasn’t something anybody “should bellyache about.” Sen. Chuck Grassley, who actually co-authored a law enhancing protections for inspectors general, meekly asked for “further explanation from President Trump” after he unduly fired 17 of them. The country needs the likes of Goldwater and Brooke when all it has is Grassley and Tillis.

To be fair, the only politicians punished for Trump’s attempt to steal the 2020 election were the handful of Republicans who dared to call him out for it and who were either primaried out of office or chose not to run for reelection. Any remaining GOP politicians with a conscience know full well that it is they who would pay the ultimate political price for questioning Trump.

No, the ultimate blame for Trump’s egregious abuses of power lies not with GOP politicians but with those who knowingly voted back into office a convicted felon, an adjudicated rapist, and an impeached insurrectionist. Trump is a small man who repeatedly expressed his intent to use the office of the president to settle petty, personal grievances and to wage bureaucratic war on his political foes. You cannot accuse him of not following through on those promises.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.