More than two and a half years after the certification of the Electoral College votes in the 2020 presidential election, most Republican politicians’ responses to questions about January 6 fall into one of two categories: a reflexive embrace of former President Donald Trump’s assertion that then-Vice President Mike Pence and Congress should have rejected states’ election results, or a rejection of it.

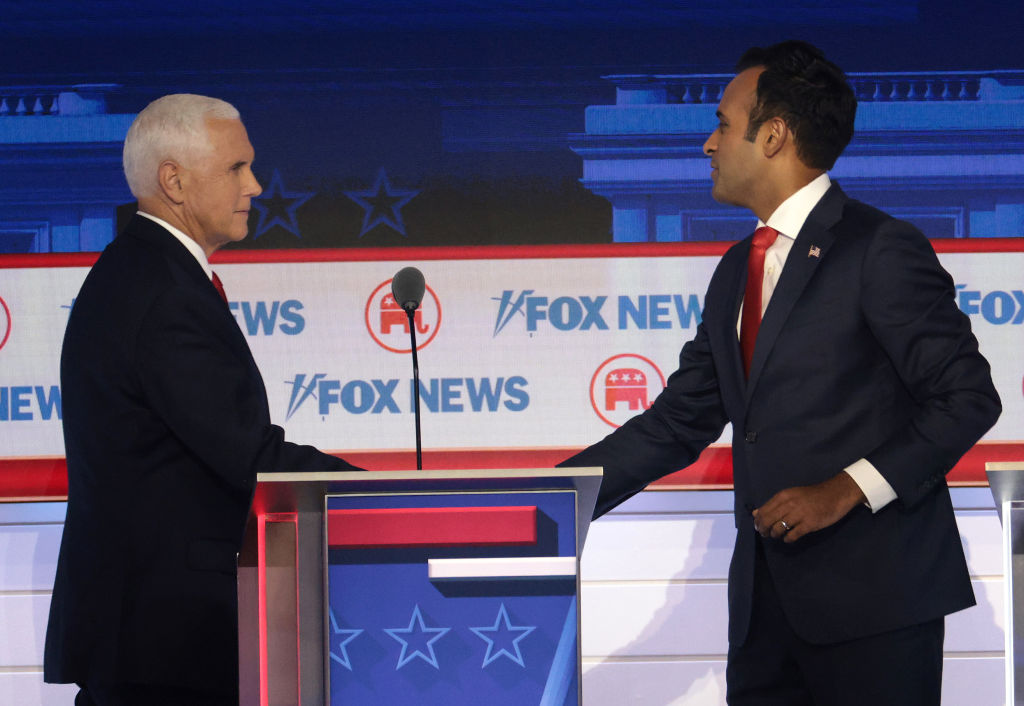

But Vivek Ramaswamy—a biotech entrepreneur and presidential candidate—has tried to chart a third path. Instead of forthrightly embracing or rejecting Trump’s baseless claims of election fraud and the attack those claims inspired, he argues that Pence missed out on an “opportunity for heroism.” Had he been vice president at the time, Ramaswamy has said he would have assuaged voters’ concerns about election security while also ensuring a peaceful transition of power. (In his 2022 book, Nation of Victims, Ramaswamy condemned January 6 as a “dark day for democracy.”)

Ramaswamy’s answers to questions about January 6 have been confusing—but could his counterfactual plan have worked?

What has Vivek said about the role of the vice president on January 6?

Ramaswamy wasn’t asked directly about whether Pence did the right thing on January 6 during the first GOP presidential primary debate on August 23. His response to a question from National Review reporter John McCormack afterward, however, gestured toward some sort of “national compromise” to unite the country—a concept he developed further on Meet the Press a few days later.

After ticking through a suite of election reforms he would prefer—“We need single-day voting on Election Day, we need paper ballots, and we need government-issued ID matching the voter file”—Ramaswamy suggested that, if he had been vice president on January 6, 2021, he would have tried to make certification of the Electoral College votes contingent on the passage of those reforms into law.

“In my capacity as president of the Senate, I would have led through that level of reform, then on that condition certified election results, served it up to the president, President Trump, then to sign that into law, and on January 7, declared the reelection campaign pursuant to a free and fair election,” he said.

On Tuesday, Ramaswamy tweeted what he described as a “practical solution” that “prevents U.S. elections from poisonous federal overreach but also delivers robust, permanent reform to ensure election integrity and the peaceful transition of power do not again come into direct conflict.” It includes the three aforementioned reforms, plus making Election Day a national holiday and passing Rep. Bryan Steil’s American Confidence in Elections Act, a Republican proposal meant to provide states with “tools to bolster voter confidence and improve election integrity,” according to the bill summary.

Why wouldn’t Ramaswamy’s plan have worked?

Let’s take Ramaswamy’s claims about what he would have done on January 6 piece by piece.

“In my capacity as president of the Senate, I would have led through that level of reform, then on that condition certified election results …”

Vice presidents typically advocate—both publicly and privately—for the policy agenda of the administration in which they serve. But that’s an informal power, unrelated to his or her title as president of the Senate, which is itself almost entirely a ceremonial role and comes with no authority to introduce legislation.

There’s a reason the vice president is rarely seen in the Senate chamber. He or she can break ties when a Senate vote is evenly split—as Kamala Harris has done 31 times and Mike Pence did 13 times—but that’s basically the extent of the vice president’s legislative power. The rest of the job of “president of the Senate” is procedural, including such responsibilities as recognizing senators to speak and enforcing decorum. Even the president pro tempore of the Senate—chosen by the Senate to preside in the vice president’s absence—doesn’t do the job all that often, typically designating a junior senator to do it instead. On the dais, the presiding officer is advised by the Senate parliamentarian—and that advice is very rarely overruled.

During joint sessions of Congress—special sessions where both chambers are together in the same room, such as for a foreign dignitary’s speech or the certification of the Electoral College votes—the vice president’s role is even more limited, because joint sessions by definition have no legislative function. Bills can’t be introduced, debated, or voted on during joint sessions.

And the 12th Amendment to the Constitution strictly limits what happens during the joint session to certify Electoral College results: “The President of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted.”

Had Ramaswamy been Trump’s vice president and wanted to attempt to make the certification of the Electoral College votes conditional on the passage of some other election-related bill, he could have worked with like-minded lawmakers to draft such legislation, while also threatening to somehow thwart the Electoral College certification, in the weeks leading up to January 6.

But what he could have actually done to stop the certification of electoral votes is unclear. The rules for the joint session at which the Electoral College votes are counted come from the Constitution, the Electoral Count Act (replaced last year by the Electoral Count Reform and Presidential Transition Improvement Act), the rules of the Senate, and a concurrent resolution (a rules agreement between the chambers that doesn’t require the president’s signature or have the force of law). None of them allow for the vice president to dissolve the joint session.

The only thing that can interrupt the process is an objection submitted in writing. In 2021, an objection needed support from both a representative and a senator to be sustained—but next time, it will require one-fifth of both chambers due to the reforms to the law passed last year. An objection sends both chambers into separate sessions to debate and vote on the objection before reconvening. (On January 6, 2021, both chambers were in the midst of debate over an objection to Arizona’s votes when the mob breached the Capitol.)

If the vice president tried to finish the joint session early or skip certain states’ votes, members of Congress would almost certainly have objected. And if the vice president were to declare such objections out of order, the tellers and clerks on the dais would probably have refused to continue, according to a December 2020 Twitter thread by Ira Goldman, a former legislative counsel in the Senate. That would have made January 6 more contentious than it already was and potentially prolonged the process, but it wouldn’t have prevented Congress’s eventual certification of the vote.

“… served it up to the president, President Trump, then to sign that into law …”

If both chambers, operating in normal, non-joint session circumstances, had passed a bill containing election reforms, the president could have chosen to sign it into law. But the Electoral College vote count is simply a count, not a piece of legislation, and thus does not require the president’s signature.

“… and on January 7, declared the reelection campaign pursuant to a free and fair election…”

Ramaswamy seems to suggest that the vice president could have waited for Trump to sign an election-reform package before “declaring” the winner of the presidential election. But past precedent suggests that the vice president doesn’t have a declarative role in the process.

Notably, an early draft of the Electoral Count Act in 1876 stated that the vice president would “announce the state of the vote, and the names of the persons, if any, elected, which announcement shall be deemed a sufficient declaration of the persons elected President and Vice President.” But in 1886, the House cut that passage out in order to “prevent the President of the Senate from doing more than announcing the state of the vote as ascertained and delivered to him by the tellers.”

There were a few instances in the late-19th century in which the concurrent resolutions for the joint session did include language allowing the vice president to announce the winner, but every concurrent resolution since 1901 has been in line with the Electoral Count Act. And last year’s reforms clarified that the president of the Senate’s duties in presiding over the joint session are “solely ministerial.”

“We have a system—some people hate it, some people love it,” says Jack Maskell, a former legislative attorney for the Congressional Research Service. And barring a constitutional amendment—or a constitutional crisis—“that’s the way it works.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.