South Korea has begun to publicly discuss what was once unthinkable: pursuing its own nuclear weapons program. Such a move is unlikely to deter North Korea—but it could alienate Seoul’s most important ally.

North Korean leader Kim Jong Un has spent President Joe Biden’s time in office pledging to “beef up” his nuclear arsenal while testing a record number of missiles. Between Biden’s abandonment of America’s Afghan allies, and Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine, South Koreans increasingly question the United States’ commitment to their defense.

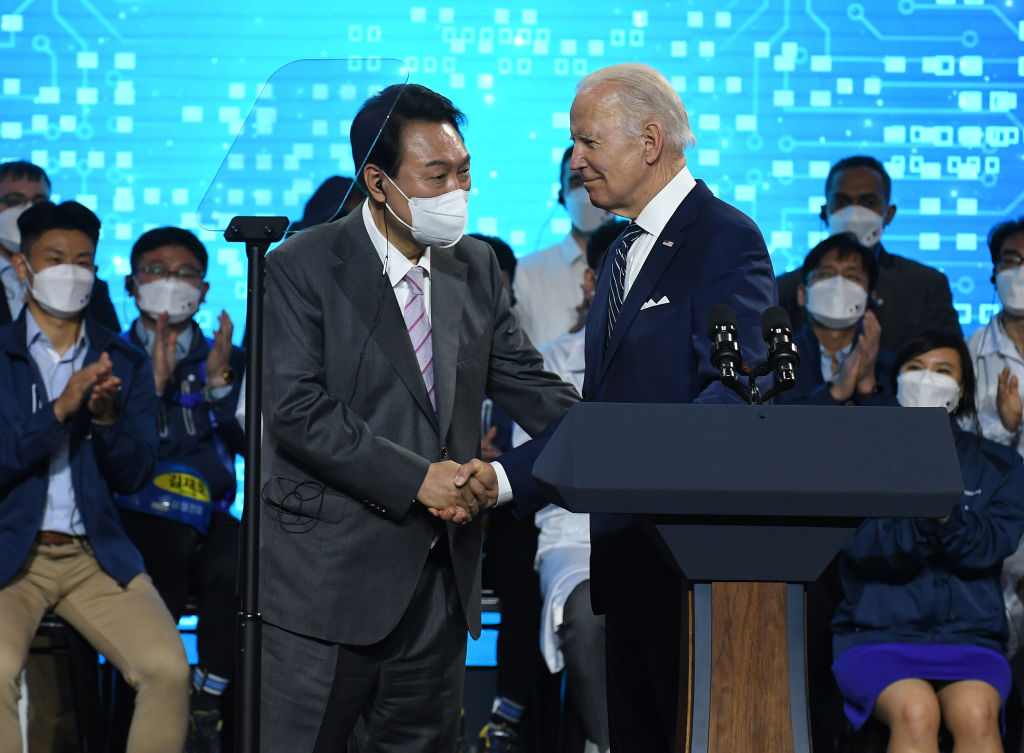

“It’s possible that the problem gets worse and our country will introduce tactical nuclear weapons or build them on our own,” South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol said this month. “If that’s the case, we can have our own nuclear weapons pretty quickly, given our scientific and technological capabilities.”

Yoon’s comments reflect a growing consensus in South Korea that the country needs more of a stake in its own national defense. More than 70 percent of South Koreans were in favor of acquiring nuclear weapons, a 2022 study by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs found. That’s as clear a sign as any of the country’s waning faith in its alliance with the United States.

For South Koreans, the invasion of Ukraine has offered a powerful lesson in the perils of sharing a border with a nuclear-armed state. The war also has strengthened North Korea’s ties with Russia and China. In May, for the first time in 16 years, both countries vetoed a United Nations Security Council resolution to impose further sanctions on Pyongyang over its ballistic missile program.

“The North Korean nuclear program has become too menacing to entrust the fate of the nation to the U.S. alone,” one of South Korea’s leading daily newspapers asserted in a January 13 editorial.

“Ideally the South will never have to arm itself with nuclear weapons. Without a North Korean nuclear threat, there would be no reason for it,” the piece continues. “But what choice does Seoul have when the North continues to develop more powerful nukes, China keeps looking the other way and the U.S.’ focus is elsewhere.”

These arguments, however, overlook America’s unique, decadeslong relationship with South Korea. The two countries have a mutual defense treaty, something Ukraine could only dream of. The Pentagon’s 2022 Nuclear Posture Review stated there is “no scenario in which the Kim regime could employ nuclear weapons and survive.”

The U.S. has maintained, without interruption, a military footprint in South Korea since the 1950s. Some 28,500 American military personnel—along with nuclear-armed submarines, heavy bombers, and stealth fighters—are meant to deter an attack.

“That demonstrates U.S. credibility and resolve to protect South Korea, because it’s not just Korean lives, it’s also American lives that are at stake,” said Andrew Yeo, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and chair of its SK-Korea Foundation. “But the Koreans still feel a bit of angst and there’s always this gap about whether they can fully trust the United States.”

Another invasion by North Korea doesn’t appear imminent, but that doesn’t mean its aggression has stopped.

In 2022 the country conducted more than 100 missile tests—a new record—with little international response. American and South Korean officials recently assessed that Pyongyang was preparing for its seventh nuclear weapons test, which would be the first in more than five years. Kim formally declared North Korea a nuclear state in September and vowed “there is absolutely no denuclearization, no negotiation, and no bargaining chip to trade in the process.”

This rhetoric has some in the U.S. and South Korea thinking less about diplomacy and more about more deterrence.

A recent report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Korean Peninsula Commission recommended the U.S. consider laying the “pre-decisional groundwork to prepare for the possible redeployment of low-yield, or tactical, nuclear weapons to South Korea.” Yoon also raised that option in his remarks this month. (Washington withdrew its nuclear weapons from the country in 1991 in an ultimately one-sided gesture of non-proliferation on the Korean Peninsula.)

“I think we can accomplish what we need to do—which is contain and deter, and then move toward a long-run solution of denuclearization—without” redeploying American nukes to the peninsula, Harvard University professor Joseph Nye, co-chair of the commission and former assistant secretary of state, said during a briefing on the report. “Would you really enhance our position? Would you really change the position of North Korea? I think the answer is no.”

South Korea going it alone also seems unlikely—at least for now.

“It would severely damage the U.S.-South Korea alliance, and there would even be questions about whether sanctions would be put in place against South Korea for building nuclear weapons and violating the NPT,” said Yeo. “There’s also a strong reputational cost as well if South Korea were to build its own nuclear weapons.”

If Seoul is unlikely to pursue an indigenous atomic arsenal, and Washington is reluctant to redeploy, why all the talk? It could be a bid for renewed assurances from the U.S.—and greater input in nuclear planning and operations. “By saying you’re going to build your own nuclear weapons,” Yeo suggested, “it’s in some sense a warning to Washington.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.