There are many ways to measure Joe Biden’s decline, political and otherwise, but here’s one that’s unexpected. One of the weakest House speakers in living memory is running rings around him in a high-stakes negotiation.

Imagine being routed by a guy who needed 15 ballots and boatloads of concessions to persuade his own caucus to choose him, very grudgingly, as its leader.

It’s a sacred rule of modern right-wing politics that the GOP must pretend to care about federal spending if—and only if—a Democrat is president, and so a debt-ceiling landmine was set the moment Republicans clinched a House majority last fall. But there was every reason to think that landmine would end up wounding Kevin McCarthy when it went off far more gravely than it would Biden.

The fight in 2011 was different. John Boehner led a huge House Republican majority and claimed a mandate to cut spending after Tea Party candidates swept to victory a year earlier. An electoral backlash to TARP, the 2009 stimulus package, and Obamacare all but required him to play hardball with Barack Obama over the size of government. In that context, it wasn’t silly for the right to believe that the public would rally behind them.

McCarthy, on the other hand, leads a tiny majority following an election in which his party badly underperformed expectations. He’s viewed suspiciously as a squishy holdover of the pre-Trump Republican establishment by a base that’s grown more populist than it was 12 years ago, further weakening his hand. And his demands for restraints on government seem hypocritical after the spending binge of the Trump era.

Three times between 2017 and 2021 House Republicans voted to raise the debt ceiling, demanding nothing from the White House in exchange for doing so. “That’s a very, very sacred thing in our country, debt ceiling. We can never play with it,” President Donald Trump warned in 2019. “They can’t use the debt ceiling to negotiate.” For the GOP to turn around in 2023 and take this hostage after its solemn warnings against hostage-taking is plainly ridiculous.

So McCarthy seemed poised for disaster. The Jacobins in his conference would pressure him into making outlandish demands of Biden, like insisting on a balanced-budget amendment. Biden would laugh him off. McCarthy would then reduce his demands, angering the Jacobins and revealing to the White House how soft his spine was. Biden would call his bluff by insisting on a clean debt-ceiling hike or bust, refusing to negotiate further; furious House Republicans would then resolve not to raise the ceiling until the president came back to the bargaining table.

McCarthy would be left with an impossible choice, either forcing a default on the national debt or capitulating to Biden by passing a clean debt-ceiling increase with mostly Democratic votes. The latter would end his speakership, the former would end America’s creditworthiness and the GOP’s chances in 2024. A weak leader would come to ruin one way or another and his caucus would be left in chaos.

That’s not how things have played out, to my great surprise.

Joe Biden’s “strategy” for beating McCarthy and his caucus on the debt ceiling turns out to have been no strategy at all. Instead he made an all-in bet on a single proposition, that McCarthy wouldn’t be able to persuade 218 Republicans to pass anything he proposed.

Which was a reasonable wager, in fairness. The narrowness of his majority left the speaker with almost no margin for error. Legislation that made only modest demands on spending would be torpedoed by the Jacobins as unserious. Legislation that made draconian demands would spook moderates representing swing districts who are worried about their left flanks.

Anything McCarthy put on the floor would inevitably fail. And once it did, he’d need to concede that a clean debt-ceiling increase with Democratic help was the only way to avert default.

Imagine Biden’s shock, then, when McCarthy did pull together 218 Republican votes for the Limit, Save, Grow Act. You might not need to imagine it, actually; if you’re like me, you experienced that shock firsthand.

Jacobin Republicans did something highly uncharacteristic in this case. They behaved prudently, recognizing that passing something was essential to strengthening McCarthy’s hand against Biden. Rather than pander to their most nihilistic Newsmax-watching populist constituents by insisting on maximum concessions, they bit the bullet on a bill that does nothing to limit the spending that’s actually driving America’s enormous debt.

Yet in talks with Mr. Biden, Speaker Kevin McCarthy and his lieutenants have focused almost entirely on cutting a small corner of the budget — known as nondefense discretionary spending — that includes funding for education, environmental protection, national parks, domestic law enforcement and other areas. That budget line accounts for less than 15 percent of the $6.3 trillion the government is expected to spend this year. It is not outsized, by historical standards. It is already projected to shrink, as a share of the economy, over the next decade.

…

If Republicans could somehow persuade Mr. Biden to accept the full round of discretionary spending cuts contained in the fiscal bill the House passed last month, it would do little to alter the nation’s overall spending trajectory over the next decade. Those cuts would reduce federal spending by about $470 billion in 2033 and likely save about $100 billion that year in borrowing costs, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Total government spending would then be just under 24 percent of the economy — or nearly exactly what it is today.

Nothing on entitlements, nothing on defense. Imagine America speeding toward a fiscal cliff at 55 miles per hour; McCarthy’s bill doesn’t slam the brakes or jerk the wheel so much as it reduces that speed to 54 miles per hour. That’s a rout for Democrats on the substance of the debt-ceiling standoff.

But on the politics of it? As of today, with a federal default possible in less than a week and credit agencies starting to get antsy, Kevin McCarthy and House Republicans remain the only players in Washington to have passed a bill that would raise the debt ceiling. And there’s nothing in that bill that would obviously scare swing voters like, say, reforms to Medicare would. Spending caps, expanding energy permitting, raising work requirements to receive food stamps, and recouping unspent COVID aid: Those are the nuts and bolts of what the GOP wants.

If Joe Biden and his party would rather default than accede to a suite of demands that a centrist voter might plausibly regard as reasonable, which party is more likely to be blamed for the economic chaos that ensues?

Let’s check the polling.

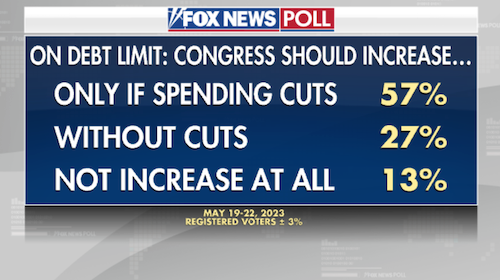

On Tuesday a new CNN survery found 60 percent of Americans believe that spending cuts should accompany any increase to the debt ceiling. That figure includes 58 percent of independents and 45 percent of Democrats. Yesterday Fox News followed up with data confirming that topline:

Support for a clean debt-ceiling hike has slipped below a third of the population.

It gets worse for Democrats. According to Fox, more Americans would blame Biden for a default than would blame House Republicans, 47-44. One in 5 members of the president’s own party would hold him responsible. It’s tempting to chalk that up to political gravity—“the buck always stops with the president in public opinion”—but it’s not true in this case. In 2011, across six major surveys, House Republicans routinely bore more blame for the debt-ceiling standoff than Barack Obama did, sometimes by wide margins.

Why? What happened between then and now?

The pandemic happened, for one thing.

By no means is COVID responsible for all of the growth in the national debt since 2011, but the supernova of spending between 2020 and 2022 has sharpened Americans’ sense that current trends can’t continue, I suspect. In 2011, the year of the first debt-ceiling standoff, the debt stood at just under $15 trillion. In 2023, as McCarthy and Biden work toward a deal, it’s more than twice that amount.

Under those circumstances, and in a period of high inflation, seeking new caps on federal spending is the least (literally!) a minimally conscientious government should do.

Trump also happened between the last debt-ceiling crisis and the current one, of course.

In 2011, with Paul Ryan banging the drum about entitlement reform, Americans understandably might have been nervous that Tea Party Republicans would settle for nothing less than cuts to Medicare and Social Security as a condition of raising the debt ceiling. In 2023, with Ryan in the wilderness and Trump having remade the right as a nationalist project, Republican leaders have sworn repeatedly that entitlements won’t be touched. Trump opposes it, McCarthy opposes it, Ron DeSantis opposes it. The most memorable moment of this year’s State of the Union was Republicans heatedly agreeing with Biden that the third rail must not be touched.

It’s because McCarthy’s bill promises to do nothing meaningful to shrink the debt, ironically, that many voters might feel comfortable supporting Republicans in this standoff.

There’s another reason the GOP has fared better in this crisis than it did in 2011, though. Kevin McCarthy has handled the retail politics of the standoff much better than Joe Biden has.

To all appearances, Biden had no fallback plan once the speaker pulled a rabbit out of his hat by passing Limit, Save, Grow. He continued to insist that he wouldn’t negotiate over the debt ceiling even as he welcomed McCarthy to the Oval Office to negotiate over, er … budgets. In Biden’s telling, if Democrats reach a compromise with Republicans on spending and Republicans then raise the debt ceiling, those are two entirely separate and unrelated legislative acts. The second has nothing to do with the first.

The commander in chief has been reduced to semantic distinctions to explain his acquiescence to Republican hostage-taking.

That’s not all. The White House hasn’t pushed hard on raising new revenue in exchange for agreeing to spending cuts, disappointing Democrats. Nor has Biden aggressively attacked McCarthy and his caucus for wanting to slash discretionary programs on which many Americans depend. Instead he’s taken a “20th century approach to high-stakes negotiations—all done behind closed doors, with an occasional designated leak of information designed to shame the other side,” per the Washington Post.

McCarthy, on the other hand, has begun briefing the press multiple times per day, giving the GOP essentially unchallenged control of the daily messaging on negotiations coming out of Washington. He’s been shrewd about it, too: Rather than coming off like some wild-eyed budget-slasher (which he emphatically isn’t), he’s been genial, reassuring about averting a crisis, and even complimentary of the White House negotiators across the table. The Republican Party, which often seems frighteningly unhinged in the Trump era, doesn’t sound that way at a moment when it should be especially easy for Democrats to argue that it is.

Even Matt Gaetz thinks the speaker is doing a “good job” lately, if only because he knows his job is on the line if he doesn’t.

Biden has sounded like more of a loose cannon than McCarthy has. Lacking a workable strategy to win this standoff, the president has begun ruminating about invoking the 14th Amendment if a deal can’t be reached with Republicans. That’s not just constitutional kookery, it’s political malpractice. “If the administration declares the debt ceiling unconstitutional, only to have the Supreme Court declare the maneuver unconstitutional, then Biden owns the market chaos that would follow,” Ezra Klein rightly observes. Biden’s presidency was supposed to restore a fidelity to “norms” in post-Trump America. Seizing power from the legislature to raise the debt ceiling unilaterally would be Trumpier than Trump.

The great irony in all of this is that a crisis that seemed destined in January to bitterly divide Republicans has begun to divide Democrats instead.

On Thursday morning Punchbowl News reported that House Republican leaders feel increasingly confident that they’ll reach a deal with Biden soon and that a majority of the conference will support it. Leaders in the other party are … not as chipper. “The anger in the House Democratic Caucus right now is palpable,” Punchbowl claimed. “Many rank-and-file Democrats feel as if they’re going to be asked to vote for a package that is slanted toward Republican demands with little for them in return.”

Some have begun to question the White House’s “leadership” in this episode, allegedly. Other outlets are hearing the same, that Democrats are wondering why Biden hasn’t given a national address explaining how the average American would suffer if Republicans end up not raising the ceiling. They want the president on offense, blasting the GOP for ransoming the creditworthiness of the United States. Instead he’s doing smiley press availabilities with McCarthy before meetings.

“The old man got rolled by a guy whom Trump calls ‘My Kevin’” is not a perception that will help Biden calm restlessness within his party about the prospect of a second presidential candidacy.

On the contrary, if Punchbowl is right and a deal on Republican-friendly terms is reached, Democrats in both chambers will be cornered. Hakeem Jeffries and Chuck Schumer will be stuck whipping votes for a “compromise” that their progressive constituents hate. If they succeed and the bill passes, the left will accuse them of having succumbed to extortion. Disenchantment with Biden will grow.

If they fail and the bill goes down in flames, Democrats will be on the hook for default because they failed to approve a compromise negotiated by their own leader. The president will look pitifully weak, having lost control of his party. Angry liberals will demand to know why the debt ceiling wasn’t raised last year, when the party controlled both chambers of Congress. Some already are, in fact.

What was supposed to have been a fiasco for one party will have become a fiasco for the other.

Democrats still have a chance to win the political fight over the debt ceiling. A good one, too.

Never underestimate the Republican Party’s willingness and ability to sabotage itself.

Conservatives in the House have also begun grumbling to reporters about the outlines of the deal that’s coming together, warning that McCarthy won’t get 218 Republican votes for it.

The wisdom of the GOP’s position to this point lies in recognizing that the debt-ceiling standoff is about politics, not policy. Contra Mike Lee, who seems intent on making the same old mistakes, “substantial spending and budgetary reforms” aren’t happening in a government where the presidency and the Senate are controlled by Democrats. They might plausibly have happened in 2017, when Republicans controlled the government, but I don’t recall Sen. Lee making any ultimatums toward President Trump at the time.

McCarthy’s bill is the art of the possible, modest on substance but clever in how it’s managed to put Democrats on the defensive. Republican voters crave a fight, but not because they care about “substantial spending and budgetary reforms,” lord knows. They crave it for its own sake. The House GOP has delivered a fight, and is winning it. Whatever ends up on Biden’s desk in the end is all but guaranteed to reflect right-wing priorities more so than left-wing ones. The liberal tears will flow.

Unless, that is, the Mike Lees of the House and Senate preempt the “Democrats at each other’s throats” narrative with a more media-friendly one about Republicans at each other’s throats. They’re plenty capable of being that foolish, especially with you-know-who egging them on for his own cynical reasons.

Losing is this party’s specialty nowadays, almost its reason for being. If McCarthy overcomes that and produces a win, we’ll need to consider seriously that we’ve underestimated him.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.