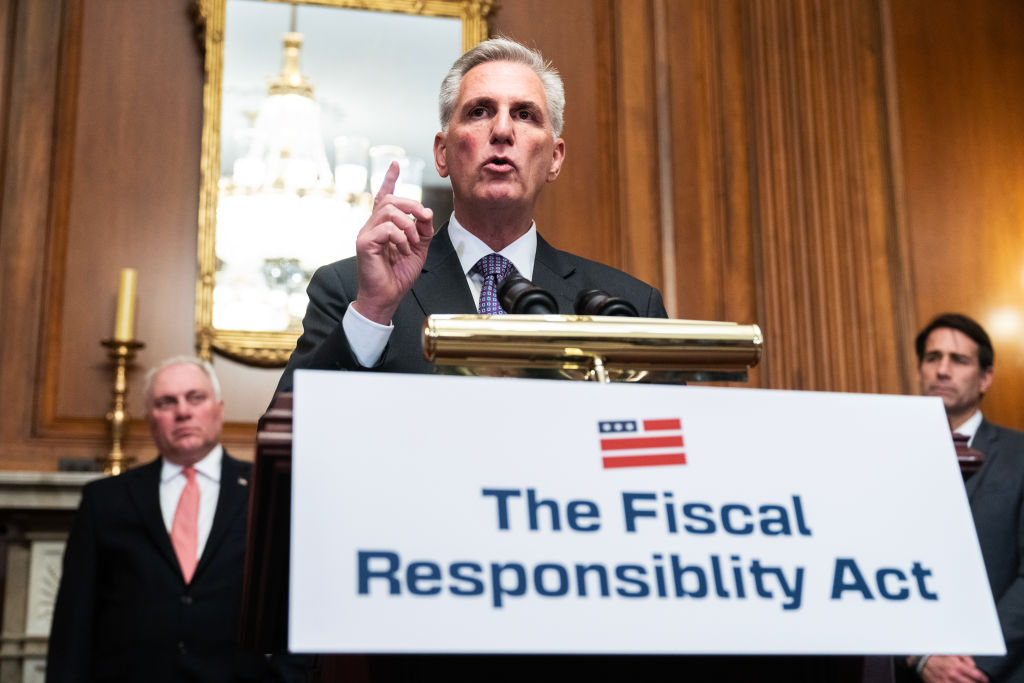

On Tuesday I compared Kevin McCarthy’s stewardship of the debt ceiling standoff to Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger’s stewardship of Flight 1549. In both cases, against all odds, a certain disaster was averted by the almost miraculous skill of the pilot.

After Wednesday night’s House vote, that comparison no longer feels fair—to McCarthy.

Sullenberger was still forced to crash-land on the water, after all, surviving by the skin of his teeth. McCarthy ended up gliding in for an uneventful landing at the local airport, grinning and thumbs-upping the whole way.

And he did it despite never having flown a plane before.

The final House tally was 314-117. Supermajorities of both parties supported the deal brokered by the speaker and the president. The margin less resembled a white-knuckle Tea Party hostage crisis circa 2011 than a humdrum early 1990s budget negotiation.

And so, with a heavy heart, I must concede that the moment calls for a bit of pundit accountability.

In January I warned moderates in both parties that it wasn’t too soon to file a discharge petition in the House aimed at forcing a clean debt ceiling hike this spring. McCarthy had made too many concessions to the Jacobins in his caucus in exchange for their votes for speaker, most ominously by reducing the threshold needed to force a vote on ousting him. He’d be perpetually under their thumb, guaranteeing a default if moderates didn’t take drastic action. “The nuts in the new House majority are really going to do it,” I warned.

They did not, in fact, do it. They didn’t get close to doing it.

Steve Hayes would be within his rights at this point to haul me into his office and pose the fateful question, “What would you say you do here?”

In my defense, though, hardly anyone expected this plane to land without incident. The realistic best-case scenario was that Republicans would pass a bill proposing unpopular draconian spending cuts, Democrats would laugh and declare it dead on arrival, and a sweaty McCarthy would reluctantly confront the fact that no compromise between fightin’ conservative populists and liberals was possible. Either he’d placate his base by defaulting or agree at the eleventh hour to pass a clean debt ceiling bill with mostly Democratic support, ending his speakership.

The realistic worst-case scenario was that House Republicans would prove so dysfunctional that they’d fail to pass any bill. That would leave McCarthy in the same conundrum described above, but with his caucus and his party looking pitiful and incompetent instead of radical and recalcitrant. Republicans can’t even agree among themselves, Democrats would crow. They can’t govern. It would be a fiasco for the American right.

The least likely outcome was the actual outcome, a soft landing. How did I—I mean, er, we—get it so wrong?

Let’s go point by point.

Republican hearts weren’t in this fight.

This was my biggest mistake in the January column.

I wrote then that I wasn’t very worried when the House GOP took the debt ceiling hostage in 2011. What worried me this time was that the serious fiscal conservatism of the Tea Party era had given way to confrontation-for-its-own-sake lib-owning in the Trump era. Conscientious fiscal hawks a decade ago wouldn’t have allowed a default, knowing what the economic fallout might look like. But nothing was stopping the Joker faction of Matt Gaetz, Paul Gosar, and other misfits from whipping up grassroots enthusiasm for a calamity, scaring most of the rest of the Republicans caucus into going along.

In The Dark Knight, so too in right-wing politics: Some men just want to watch the world burn.

I wasn’t totally wrong. Recall that the Joker himself endorsed default more than once recently, probably because he views an economic meltdown as conducive to his return to power.

But in hindsight, I had it backwards. Precisely because they were serious about cutting spending, the Tea Partiers were more likely to dig in and drag a majority of reluctant House Republicans toward a default than the Joker caucus was. They had a mandate to shrink government after their landslide victory in the 2010 midterms; they worried, rightly, that federal outlays couldn’t responsibly continue at then-current levels. The Republican base was all-in on driving the hardest of hard bargains with big-spending Barack Obama after he had beaten them on Obamacare.

It was hard back then for the reasonable majority of House Republicans to say no to conservative brinkmanship over spending. But now?

In 2023, the stakes on spending couldn’t have been lower.

The Trump-era Republican Party long ago dropped any pretense of caring about prudent budgeting, having done nothing about it when they controlled the government in 2017 and 2018. Worse than nothing, actually—they declined to slash spending commensurately after passing the Trump tax cuts, guaranteeing massive deficits. They’ve deteriorated so badly in their thinking on entitlement reform since the Paul Ryan era that each of the top two contenders for the party’s presidential nomination this year have ruled out laying a glove on Social Security.

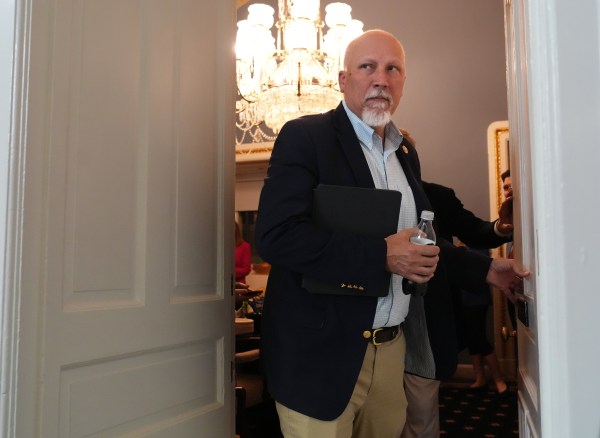

All of that being so, any Republican demands about spending in this debt ceiling standoff were destined to be meager and unserious, hardly worth tanking the global economy over. The Joker faction was sure to vote no on a compromise anyway, just because; so were the diehard fiscal hawks like Chip Roy, whose “brand” depends on stalwart resistance to taking on more debt even (especially?) when resistance is futile.

But for the great mass of House Republicans, who must have grown fatalistic by now about America spending itself into an eventual fiscal crisis, what would be gained by driving a bargain so hard that it ended up producing a default? They went along with the political theater of a debt ceiling “standoff,” realizing that their voters would expect at least that much from them, then duly rubber-stamped a meaningless compromise. I should have seen it coming.

The disappointing midterm results might have weakened radicals.

My first thought after Republicans underperformed in House races last November was that it would make McCarthy’s task in raising the debt ceiling considerably harder.

The math was simple. If Republicans held 250 seats, say, the speaker could ignore the 30 or so members in the Joker faction and still pass a reasonable debt ceiling compromise with 218. But with Republicans at only 220 or so, the Jokers would need to be won over to get anything passed.

If they weren’t, McCarthy would be forced to grovel to Democrats to get him to 218. And the Joker faction, empowered by the reduced threshold in forcing a vote to remove the speaker, wouldn’t like that.

Today I’m wondering if the GOP’s midterm disappointment didn’t end up working out for McCarthy after all.

He’d still prefer a majority of 250 than 220, surely. But the fact that so many Trump-backed candidates fared conspicuously poorly in November might have changed the calculus underlying a debt ceiling standoff within the caucus, even among the Jokers. Trump can claim all he wants that he had nothing to do with turning the expected red wave into a red ripple but even his most devoted acolytes in the House would admit privately that the results held a lesson about populist overreach, I suspect.

And if I’m wrong about them, I doubt I’m wrong about what the bulk of the Republican caucus thinks. For those who already opposed default on the merits, watching one MAGA star after another go down in flames last fall added a convenient political excuse to compromise with Democrats on raising the debt ceiling. If swing voters wouldn’t elect Kari Lake or Herschel Walker, imagine how they’ll feel about Republicans who crashed the economy.

That probably explains why House Republicans roundly ignored Trump’s recent calls for default: They’ve learned a hard lesson about the electorate’s appetite for populist radicalism, even if he hasn’t. We can only speculate how their incentives might have changed had MAGA candidates cleaned up in the midterms.

There’s another way in which a smaller majority might have helped McCarthy. In a caucus of 250, the Jokers would have spent most of their time agitating against the leadership in populist media. Their votes wouldn’t have been needed to pass legislation; they probably wouldn’t have held important committee positions. They would have vented their frustrations by rallying Republican voters to bitterly oppose the speaker’s compromise with Biden.

Maybe McCarthy still would have found 218 Republican votes under those circumstances, or maybe not. But even if he did, it’s a cinch that the grassroots blowback to the bill would have been more intense than it has been. Instead, his narrow majority forced him to include the Joker faction in the process in meaningful ways, dampening their opposition and lending a measure of populist backing to the eventual compromise. The Jacobins have been too busy governing lately to engage in nihilist rabble-rousing.

McCarthy is better at this than we thought—and perhaps Biden is too.

Kevin McCarthy is known as a good fundraiser and artful back-slapper, an old-school politician in his ability to charm. But he’s no policy wonk. And he’s certainly not the kind of strong personality one might expect would be needed to herd the many different cats in the House GOP caucus.

When the Senate scoffed at his pleas last December not to pass a lame-duck spending bill, Semafor headlined its story with a sneer: “Senators aren’t ready to let Kevin McCarthy negotiate a big boy bill just yet.” No one in Congress expected a leader as weak as him to be able to deliver in crunch time. I didn’t either.

Oops.

Again, the results of the midterm left him with little choice but to work with the Joker faction instead of sidelining them. But to all appearances, he’s been shrewd in how he’s brought them inside the tent, where they’re pissing out, instead of leaving them outside the tent, where they’d be pissing in. One of the nuttiest radicals in the populist firmament, Marjorie Taylor Greene, has become a staunch ally. Jim Jordan, who was cracked up to be a populist alternative for the speakership, was last heard praising the debt ceiling compromise. Libertarian firebreather Thomas Massie was installed on the Rules Committee, which wields tremendous power over legislation. Instead of blocking the debt ceiling bill, Massie provided the deciding vote this week on the committee to advance it.

I suspect that the speaker also leaned on his pal Donald in private not to say anything too derogatory about the legislation this week lest it spook House Republicans out of supporting it. If so, he succeeded at that as well.

All of this amounts to a pretty neat trick. How McCarthy did it, only he knows. Probably it was some combination of public concessions, of the sort he made in January to win the votes for speaker; private concessions; legislative sweeteners, like the Massie-backed section in the debt ceiling bill that would cut spending if Congress doesn’t pass appropriations bills this year; and diligent flattery over many years, as is the case with Trump.

A neat trick. And maybe the fact that no one thought he had it in him further motivated him to get a deal on the debt ceiling done. Averting a national default is nice, but showing up all the chumps who thought you’d be a helpless prisoner of the worst elements in your party? Well, that’s priceless.

Joe Biden handled things fortuitously on his end, too. Although whether that was deliberate or luck is a matter of debate.

Some Democrats told Punchbowl News they thought it was a “blunder” for Biden to have waited until after House Republicans passed their own debt ceiling bill before negotiating in earnest. Maybe—certainly it raised the risk of default—but there were benefits to that approach. Waiting “helped solidify Republicans behind the speaker and gave him more leeway than usual to pursue a deal,” Punchbowl notes, correctly. Letting McCarthy’s caucus defy the skeptics by proving they could unite behind a bill gave them an unambiguous win in this process, which may have made them more willing to compromise on the final bill.

That Biden agreed to negotiate at all after insisting that he wouldn’t let the debt ceiling be taken hostage made it a double win for Republicans, in fact, a bit of symbolic lib-owning as a prelude to a deal that did next to nothing to own the libs on the merits.

The president’s low media profile during negotiations might also have been a matter of good strategy rather than an 80-year-old failing to muster the energy to press his case. The more McCarthy’s many gaggles with reporters made him the face of the bill, with little public pushback from the White House, the harder it became for House Republicans to oppose it. When the media asked Biden earlier this week what he’d say to House Democrats to persuade them to support the bill, he declined to comment for fear that any triumphalism might antagonize Republicans into opposing it. For the same reason, I assume, he never quite endorsed using the 14th Amendment to raise the debt ceiling despite progressives pleading with him to do so.

Biden played it cool. He didn’t care that McCarthy got most of the credit. He wanted McCarthy to get the credit, knowing that was likely a prerequisite to the Republican buy-in he needed to avert a default that would have sunk his chances at reelection.

Grassroots Republicans are too consumed by the primary and culture war to care

If the American right of 2023 prioritized spending the way it prioritizes cultural revanchism, the vote to remove McCarthy as speaker would already be scheduled in the House.

Wait, scratch that. There’d be no vote to remove McCarthy because McCarthy wouldn’t have dared strike such a modest compromise with Biden.

We all knew in January that the post-Trump GOP cares less about the size of government than it does about culture war, but I underestimated how much less. Six months ago, Ron DeSantis abusing his power as governor to punish left-leaning corporations was the bleeding edge of right-wing cultural activism. Six months later, populists are no longer content to wait for politicians to spearhead initiatives against their enemies. All of the activist energy online is flowing into boycotts of companies like Anheuser-Busch, Target, and Chick-fil-A for “woke” sins great and small.

It’s much more fun to accuse your opponents of being “groomers” for holding the wrong position in cultural disputes than it is to argue over fiscal wonkery tied to the debt ceiling. And activist politics is all about fun.

That’s a lamentable, if unsurprising, turn in the seriousness of right-wing politics. But it has the silver lining of funneling grassroots passion away from seriously destructive pursuits, like crashing the global economy to prove a point about spending, and toward more innocent fun, like shooting up a case of Bud Light on camera and uploading the clip to TikTok.

The viciousness of the Republican presidential primary is also something of a surprise, at least this early in the process. I thought it’d take months for Trump fanatics to accuse Casey DeSantis of exaggerating her cancer or the governor’s spokesman of having had cosmetic enhancements but here we are on June 1 and things are already in full swing, with some of the sleaziest influencers in both camps duking it out daily on social media. It’s Kevin McCarthy’s great good luck that the debt ceiling standoff came to a head at the very moment Ron DeSantis finally entered the race and started throwing roundhouses at Trump, distracting precisely the sort of populist malcontents most likely to cry “treason” over his deal with Biden.

There’s one more difference between the Republican base of 2011 and the Republican base of 2023. Try as they might, the latter just hasn’t managed to will itself to hate Joe Biden the way it hated Barack Obama.

Opinions will differ as to why. Some will claim it’s a straightforward matter of racial resentment, with a dynamic young black president destined to antagonize a party of older white reactionaries more than an elderly, enfeebled white pre-Boomer ever could. Others will point to Obamacare and note that Obama’s agenda was more revolutionary than Biden’s despite the blowout spending levels during both administrations. Some might reason that it’s precisely Biden’s lack of charisma, the fact that he couldn’t galvanize messianic support the way Obama did, that makes him less of a threat.

Regardless, it all worked out for Kevin McCarthy the same way it’s worked out for his Republican colleagues in the other chamber. Senate Republicans have compromised with Biden and the Democrats repeatedly since 2021, including on matters like infrastructure that were coveted by Trump, with hardly any meaningful backlash among the grassroots right. The potency of the debt ceiling weapon made things a bit trickier for McCarthy, but only a bit. As I write this on Thursday, he’s unlikely to face a vote to remove him as speaker for his alleged great betrayal of fiscal conservatives.

That’s the softest of soft landings, unthinkable—to me, at least—six months ago. Congratulations to him on his, and his party’s, unlikely survival.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.