Among the many Biden administration economic policies from which Vice President Kamala Harris stubbornly refuses to separate herself, industrial policy is near the top. In speeches and campaign materials, Harris has repeatedly and vocally championed the “targeted” tariffs, subsidies, Buy America rules, and other policy measures that have been implemented over the last four years to boost U.S. manufacturing, security, and the economy. Capitolism has addressed many of the storm clouds hovering over those policies, the success or failure of which is still very much TBD, but the toss-up 2024 presidential election provides yet another: the inevitable uncertainty baked into almost all American industrial policy, regardless of its form or merits.

Economic Policy Uncertainty Matters. A Lot.

Reams of economics literature show a strong connection between the unpredictability of government economic policy—aka “economic policy uncertainty” or EPU—and corporate investment and activity in the United States. Studies have found, for example, that higher EPU causes firms to reduce short-term, long-term, and total investments. Negative effects are particularly pronounced for small businesses, bank credit supply, and in the manufacturing sector, and they can occur at the federal and sub-federal level. In one particularly interesting paper, state-level manufacturing investment was found to remain depressed after gubernatorial elections, as companies faced with pre-election EPU in one state shifted their investments to neighboring states with more stable and predictable policies.

One of the most widely cited and relevant studies on EPU, by economists Scott Baker, Nick Bloom, and Steven Davis, develops an EPU index based on thousands of newspaper articles and reveals that EPU spiked during not just major shocks like the Gulf wars or failure of Lehman Brothers, but also tight presidential elections when the future of monetary, tax, fiscal, trade, and other federal policies set, implemented or influenced by the executive branch could change dramatically depending on who wins. The authors further found that EPU, at the firm level, increases stock price volatility and reduces investment and employment in “policy-sensitive sectors like defense, healthcare, and infrastructure construction,” and, at the economy-wide level, foreshadows declines in U.S. investment, output, and employment. They’ve since updated the index to include other measures of uncertainty, as well as sub-indices for specific economic policy areas (trade, monetary policy, climate) and countries.

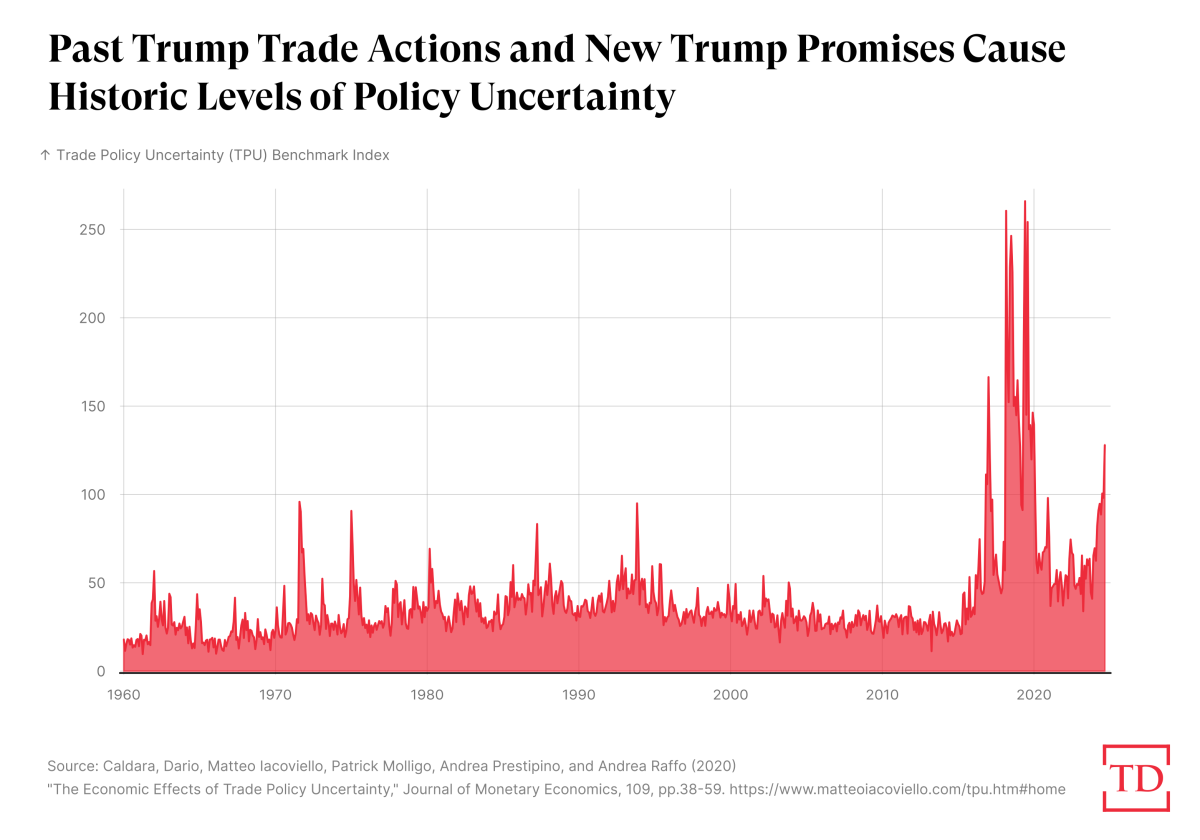

Given events here and abroad, economists have recently focused on trade policy uncertainty (TPU), again finding that higher levels correlate with less investment and economic activity in the United States, and that things that limit TPU—such as trade agreements—can mitigate some of these harms. During the Trump era—when agreements were sidetracked and major changes to U.S. trade policy were literally announced via tweet (repeatedly)—TPU was, on average, more than three times as high it was during the Obama years, nearly twice as large as TPU during Biden’s term, and the highest recorded under any president going back to 1960. This dramatic increase in Trump TPU was further found to reduce aggregate U.S. investment by 1 or 2 percent (i.e., between $23 and $47 billion in 2018).

As to why uncertainty weighs on investment and growth, economist Robert Krol provides a succinct and useful explanation, again backed by ample research:

Uncertainty makes firms less sure about the returns associated with capital expenditures or hiring. Since there are nonrecoverable costs associated with a decision to invest in capital or hire and train workers, uncertainty makes it prudent to delay capital expenditures or hiring. Uncertainty also worsens information asymmetries between lenders and borrowers. With greater uncertainty, the chances of bankruptcy increase. As a result, banks tend to delay lending to firms, slowing business expansion.

Of course, wonky studies are good and all, but the effects of policy uncertainty on an economy are really just common sense: If you were about to invest or loan out millions of dollars, especially in relation to a “policy-sensitive” project dependent on a certain law, regulation, or politician, would you maybe think twice if things were starting look dicey? Of course you would.

(And, I should note, investor hesitation is something I witnessed firsthand back when I was a corporate lawyer during the tumultuous years of Trump trade policy.)

Policy Uncertainty Is High—and Probably Weighing on U.S. Industrial Policy

With yet another close presidential election less than two weeks away, both data and anecdotes indicate that EPU is indeed again on the rise and acting as a drag on the U.S. industries most exposed to abrupt changes in federal policy. As shown below, for example, TPU during the early Biden years was relatively calm but has jumped up in recent months as the presidential race has both tightened and attracted increasing amounts of media bandwidth:

A separate measure of TPU has also been elevated in 2024, averaging about double what it averaged in 2022-23. That change, of course, is hardly surprising: One of the two major party candidates literally can’t stop yammering about tariffs (sigh); the other is kinda-sorta attacking him for it; and China remains a key talking point for both of them. Combine that rhetoric with, as we just discussed last week, the vast amount of trade policy power U.S. law gives to any president, and the aforementioned spikes are all but guaranteed.

In the real economy, meanwhile, there’s growing evidence that heightened trade policy uncertainty is affecting business decisions. The New York Times, for example, in August interviewed “two dozen American manufacturers, retailers and shipping agents,” and found that “many said they were holding off on investments and expansion given the uncertainty over tariffs on imported products and parts — especially on those shipped from China.” A month later, the Times documented how some U.S. distillers, targeted by painful retaliatory tariffs during the Trump 1.0 years, were holding off on new investments out of fear that another trade war was about to begin under Trump 2.0.

More broadly, the head of AXA Investment Managers’ macro research department told the Times reporters that he “expects [US investment] to soften in the third quarter because businesses are uncertain how policies would affect their businesses.” And just this week, Politico reported that a broad coalition of U.S. manufacturers, retailers, and agricultural producers are “bracing” for Trump tariffs and talking to Congress about possible reforms, while the Wall Street Journal said Trump’s Mexico tariff threats “keep investors up at night” and have delayed several automotive investments because the threats jeopardize the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement—“a rules-based trade pact [that] institutionalizes openness and provides legal certainty to those willing to commit capital.” Numerous other reports reiterate these corporate tariff jitters and their potential drag on U.S. and global investment.

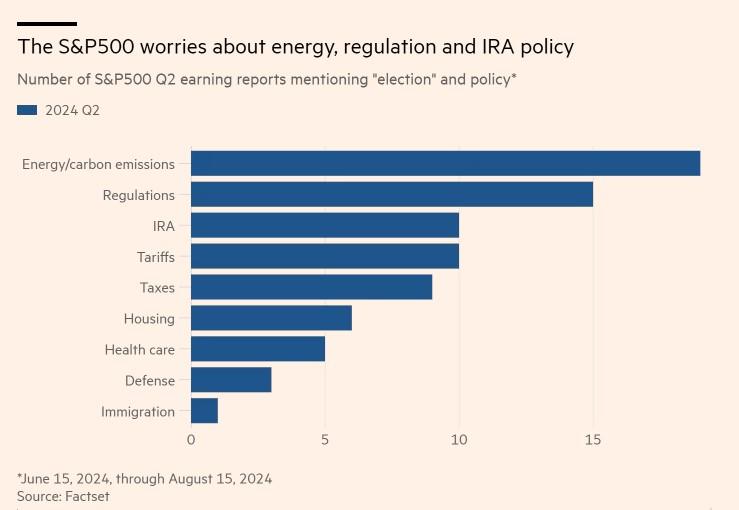

It’s not, however, just tariffs and trade-exposed industries that are feeling the effects of election-related uncertainty. Biden-era industrial policies—even ones hardwired into U.S. law via the Inflation Reduction Act—are at risk too, with attendant economic effects. As Bloomberg reported last month, for example, Trump “has campaigned on promises to end what he calls Washington’s ‘green new scam’ while abolishing regulations encouraging coal power plant closures and compelling more electric vehicle sales.” And, the article notes, even though IRA tax credits are on the books for years to come, there are numerous things a president can do to affect the flow of subsidies—and thus ding related private investment (emphasis mine):

The biggest risk isn’t in rescission of tax credits but a revision, said Kevin Book, managing director of the Washington consulting firm ClearView Energy Partners LLC. Even without a full repeal by Congress, Trump would have wide administrative power to curtail the reach of IRA tax credits by rewriting Treasury Department rules governing what projects are eligible. A second Trump administration could potentially make it easier to claim credits for industries and technologies typically favored by Republicans, such as capturing carbon and making hydrogen with the help of fossil fuels, while raising the hurdles to qualify when the subsidies target electric vehicles and renewable power.

Writing and imposing new rules could take at least 18 months — but the impact would be much more immediate. “It would chill investment immediately,” said Josh Price, a director with the Washington-based research consultancy Capstone.

Contrary to the quote above, there’s evidence that the investment “chill” has already begun. As the Financial Times documented last month, for example, a recent Goldman Sachs analysis found that “election discussions have entered management commentary earlier than in past election cycles, with some companies — particularly financials, government contractors, and those with exposure to the Inflation Reduction Act — noting that either they or their customers are postponing some investment decisions until after the election.” As a result, Goldman analysts calculate that “capital expenditure growth has been 5 percentage points lower for companies citing election uncertainty on their Q2 earnings calls.”

The FT adds that the “panicked earnings calls are reflected in actual spending numbers, too,” with much-ballyhooed U.S. manufacturing construction spending now slowing down, thanks in part to “uncertainty over the future of US industrial policy”:

According to the Atlanta and Richmond Federal Reserve banks’ latest CFO Survey, in fact, “30 per cent of firms have postponed, scaled down, delayed or cancelled investment plans because of election uncertainty.”

The FT also notes—as we’ve discussed—that U.S. manufacturing investment has been stagnant, which along with new weakness in the services sector points to a broader growth slowdown in the months ahead. The article concludes that “a tight race between two candidates, with varying implications for particular industries, is not amenable to business-as-usual” for those companies, even as the rest of the U.S. economy hums along. Thus, holding off on investment due to “changes in trade, tax, and regulatory policy… could just be an unnecessary expense” that policy-affected U.S. companies appear to be paying today.

Alas, These Are Permanent Risks

Depending on who wins in November, of course, many skittish U.S. investors might get off the sidelines and resume their spending plans once the White House’s future occupant is settled. But that still wouldn’t mean that the uncertainty has been costless or will entirely disappear. For starters, time is still money and opportunity costs are still a thing, so delays alone can be expensive (as are all the lobbyists, P.R. flacks, and economic analysts paid to predict or influence the future U.S. political climate). Market factors might also change by the time the direction of future policy is settled, thus further delaying or even scuttling investments that looked a lot smarter or more profitable last year. And, as indicated by the state-level paper above, global investors might also just look at the political and policy uncertainty here and decide it’s simply better and safer to invest somewhere else—at least in regards to policy-exposed industries. (Indeed, The Economist recently noted that the biggest threat to current U.S. economic dominance is our terrible politics!)

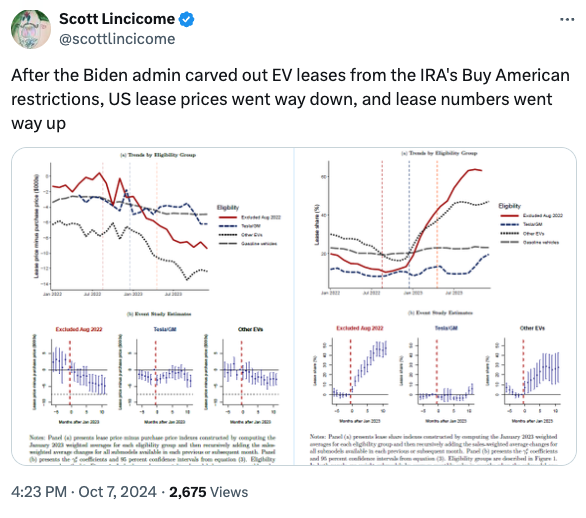

For those industries, moreover, the political risk never really goes away entirely. Instead, as we discussed last year, these kinds of problems are hardwired into industrial policy regardless of who’s in the White House because implementation always depends at some level on politicians, bureaucrats, and courts instead of market forces. The Biden administration’s own EV subsidies and regulations, for example, have been modified repeatedly, with dramatic and unforeseen effects on the U.S. market. Consider in this regard what’s happened to leased vehicles, which have exploded in popularity due to unexpected Treasury Department tweaks that expanded subsidy eligibility (just as Capitolism predicted 20 months ago, by the way):

And right in time for the election (coincidentally, I’m sure!), the Biden administration this week proposed onerous new restrictions on “Buy American” waivers, affecting sourcing decisions for dozens of products used in federally funded projects. Maybe those rule changes are good, or maybe (probably) they’re bad. But one thing’s for sure, regardless: The rules could be different from what they were last week, and related uncertainty has therefore increased.

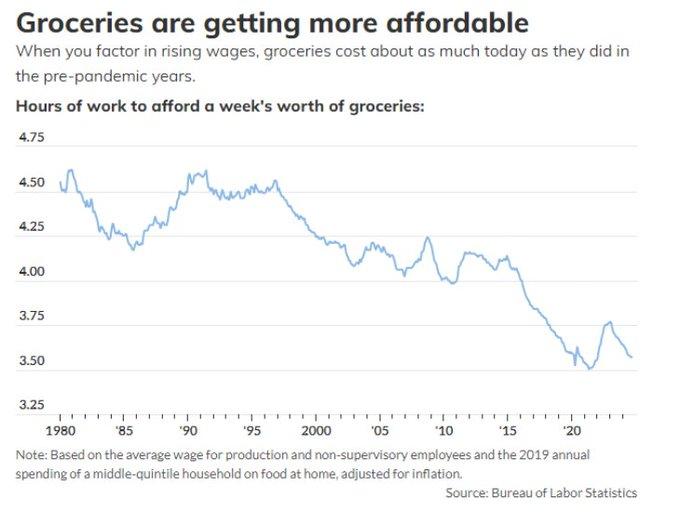

In this way, tariffs, subsidies, mandates, and other interventionist industrial policies differ greatly from freer market policies, even if both are—as is so rarely the case these days—made permanent in law. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s permanent corporate tax rate reduction, for example, might be changed via future legislation as Kamala Harris unwisely promises, but passing any law is a heavy lift these days, and as president Harris would have far fewer unilateral ways to muck with tax rates than, say, a tax credit doled out regularly by the executive branch. With the latter, a certain amount of uncertainty is simply baked in, and it’s inevitably amplified during every election season. In fact, because industrial policy is supposedly intended to induce investments that wouldn’t otherwise occur in a market economy, that spending is uniquely vulnerable to policy uncertainty. Put simply, if investments targeted by industrial policy wouldn’t—as advocates claim—exist without government involvement, anything that threatens said involvement will necessarily threaten said investment.

And, as the last few weeks have demonstrated, there’s plenty to threaten both.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.